WASHINGTON (Army News Service, July 23, 2015) -- Carl Wilkens was the only American to remain in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, which resulted in some 800,000 killed. His life was in continual jeopardy as he worked to stop the violence and shield those he knew from being murdered, he said.

Although not a Soldier, Wilkens' story echoes the Army values of loyalty, duty and personal courage. In Rwanda, said Army Chaplain (Col.) Kenneth Williams, Wilkens took a stand against the bigotry, hatred and genocide. "He's an example to us of how to stand strong in the face of adversity."

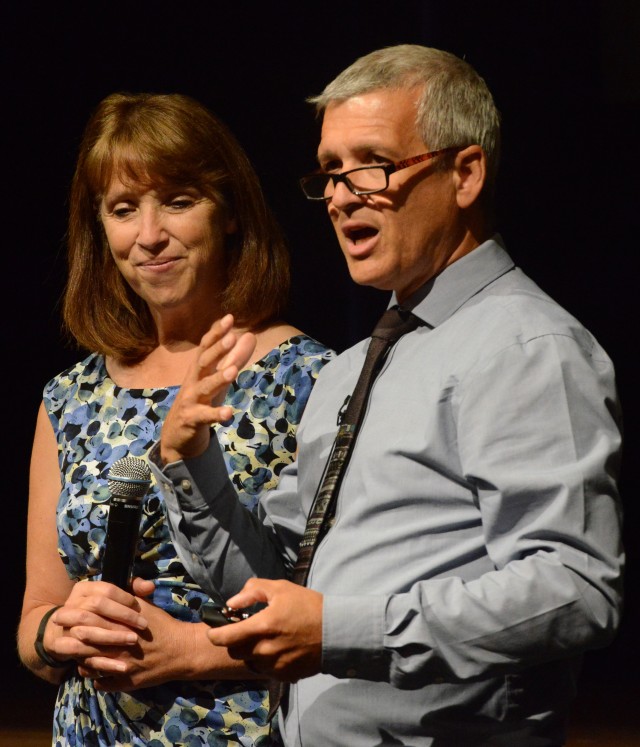

Williams, who is with the Pentagon Chaplain's Office, introduced Wilkens and his wife Teresa at a July 23 seminar called "The Fight Against Genocide." The Office of the Pentagon Chaplain hosted the event.

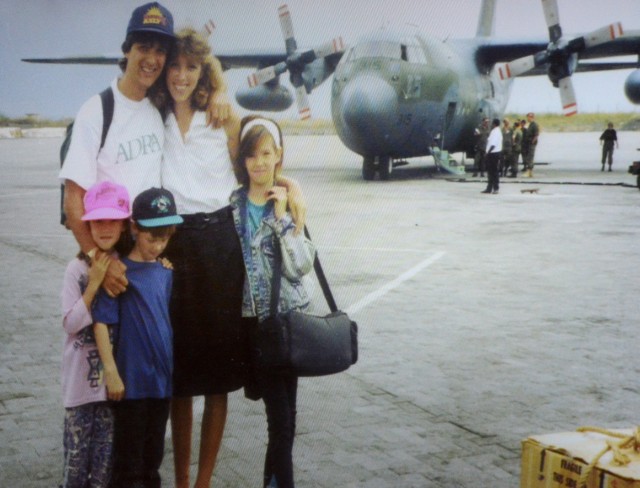

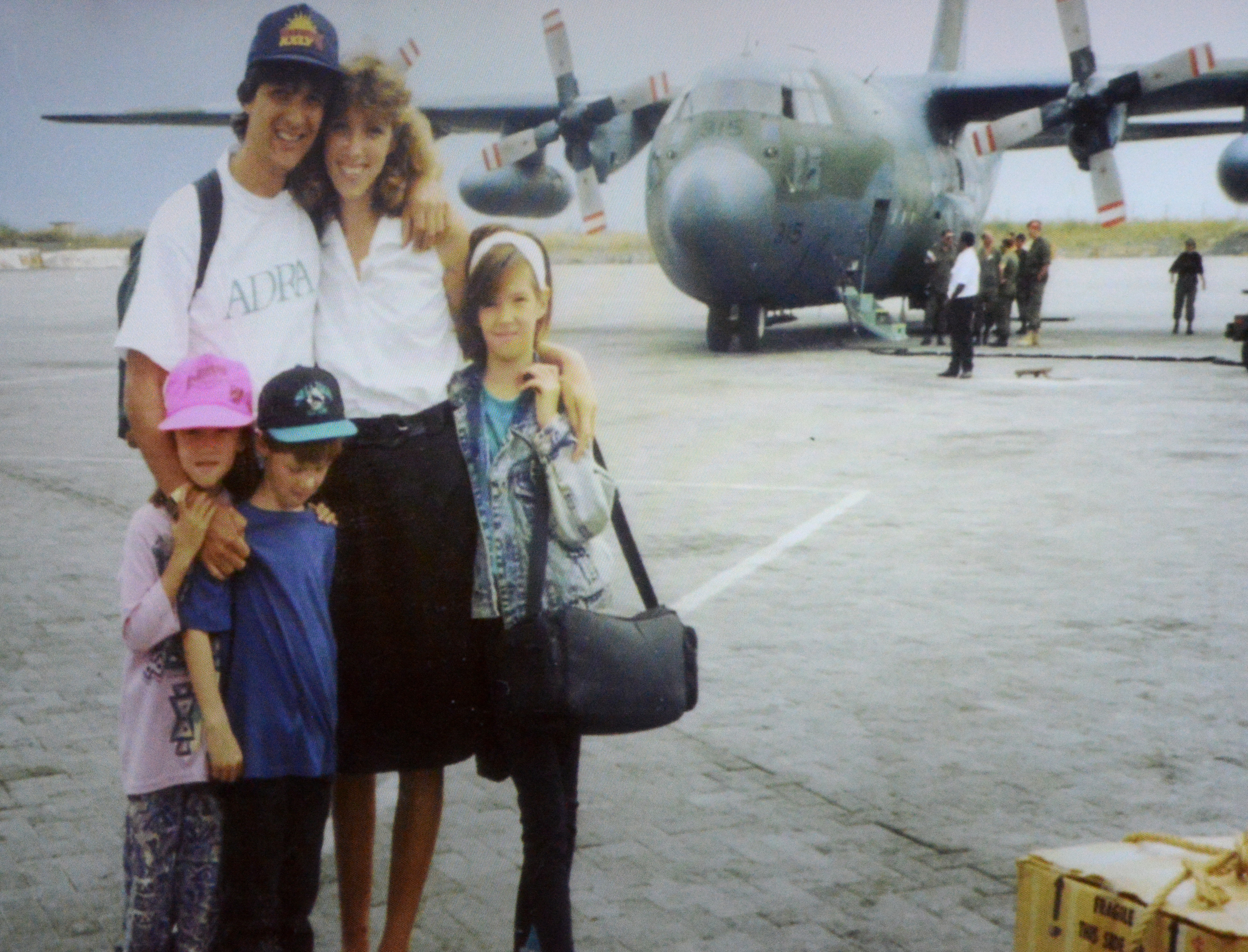

Wilkens, his wife and their three small children moved to Rwanda in 1990. At the time, he worked as head of the Adventist Development and Relief Agency International there, and was involved in various humanitarian projects.

Their children played with local Rwandans and it was impossible to distinguish between members of the Tutsi and Hutu population, as all seemed to be one happy family, he said. But that soon changed.

Outsiders mistakenly believe the ensuing genocide was a result of a history of tribal conflict between the two groups, he said. Rather, the origins of the mass murder had to do with a political power struggle. Killings were organized by certain Hutu leaders. Soldiers, police and militia then initiated the execution of Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

As violence escalated, all U.S. embassy personnel were evacuated and Americans living in Rwanda were told to evacuate as well, he said. Wilkens' family relocated to Nairobi, Kenya.

But Wilkens could not bring himself to leave, his wife explained.

"Anita was the catalyst initially for our decision to stay," she said, referring to the family's housekeeper at the time. "The four years she had been in our home, she made a positive impression. Over the years we got to know her heart and how special and kind she was, especially to our children. She really exuded love.

"Over that time period, it felt like she became part of our family," she continued. "There was never the thought that "we should get out while we still can."

Anita was a Tutsi and would have undoubtedly have been killed, he said, so staying meant that she and their security guard would at least be afforded some protection in his home in Kigali, the capital and largest city in Rwanda, where much of the killing occurred.

Wilkens said he and his wife also prayed a lot on the matter, but he admitted to having a spiritual struggle.

For the first two weeks, he described having made a bargain with God to stay, but only if he spared his life. Then, he said he came to the realization that he would be OK with whatever plan God had. Only then did he say he found peace and freedom and much of the anxiety and tension melted away.

Wilkens then looked around the Pentagon Auditorium at the men and women in uniform and spoke directly to them, saying that he knew many of them had experienced worse struggles in life and that he deeply appreciated their own sacrifices.

In the three months Wilkens remained in Kigali, he said he saw atrocities, which are too horrible to describe. But even among the worst, he saw glimpses of humanity.

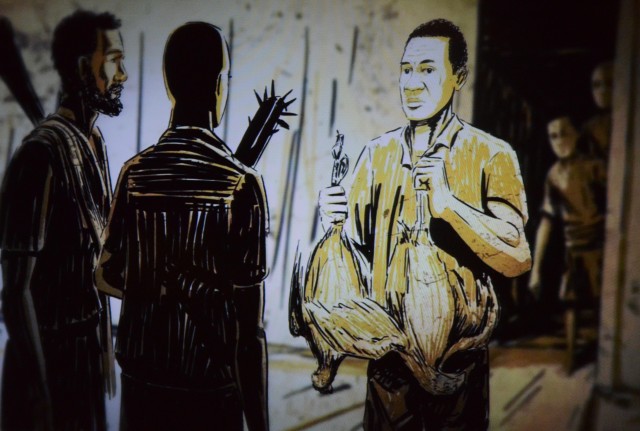

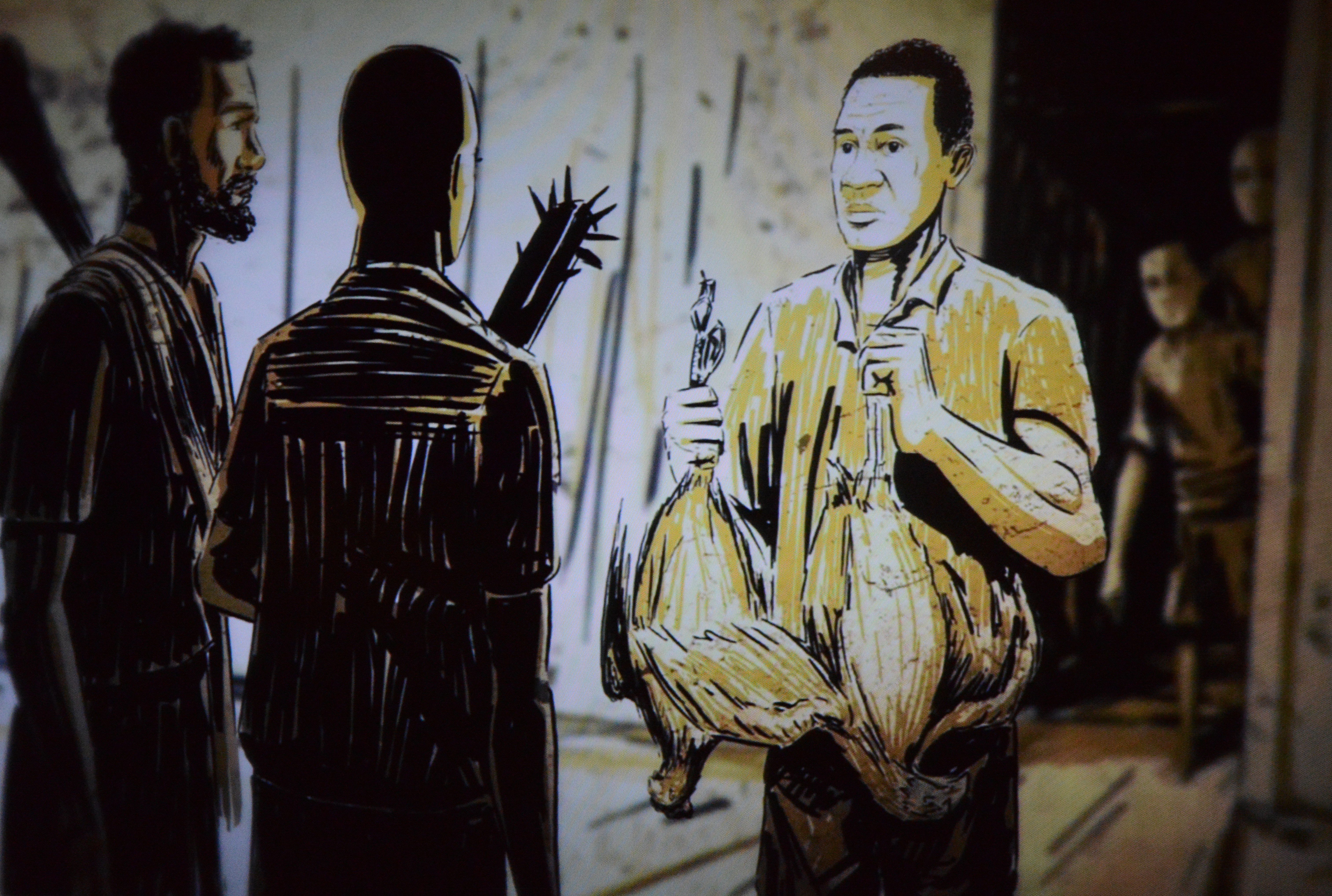

For example, a local named Gasigwa, who had been called on to aid the killers, had 40 people in his tiny home seeking protection, mostly children. When the killers would come, Gasigwa would say "I know your kids are hungry. Here, take these chickens," he said. And they would then accept the gifts and leave.

"Why didn't these guys kill everyone and then take the chickens as well" Wilkens asked. He reasoned that although these were evil men, there was still a spark of humanity in many of them.

After the genocide, many of the killers were imprisoned. Wilkens returned to Rwanda years later and visited one of the prison camps, where inmates were baking bricks for building schools.

Wilkens described the camps as being rehabilitative and not punitive in nature. In a way, he said, he felt some anger that the killers were being rehabilitated. But in another way, he said, he admired the Rwandans' compassion after such an atrocity and said ordinary citizens wanted to get on with their lives and live together in harmony once more for the sake of their children and future generations.

Wilkens reported that his former housemaid is alive and married. She and her husband, a Hutu, have two children. Their former security guard joined the Rwandan army and participated in the peacekeeping mission in Darfur.

In 2011, Wilkens authored a book about his experiences in Rwanda, titled "I'm not leaving." He now spends much of his time visiting high schools in the United States and around the world describing the genocide and offering ideas on how to prevent such events in the future.

Social Sharing