Deborah Sampson

Disguised herself as a man to serve in the Continental Army

During the Revolutionary War, women served the U.S. Army in traditional roles as nurses, seamstresses and cooks for troops in camp. Some courageous women served in combat either alongside their husbands or disguised as men, while others operated as spies for the cause. Though not in uniform, women shared Soldiers' hardships, including inadequate housing and little compensation.

Shortly after the establishment of the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates reported to Commander-in-Chief George Washington that "the sick suffered much for want of good female Nurses." Gen. Washington then asked Congress for "a matron to supervise the nurses, bedding, etc.," and for nurses "to attend the sick and obey the matron's orders." A plan was submitted to the Second Continental Congress that provided one nurse for every ten patients and provided "that a matron be allotted to every hundred sick or wounded."

In the 18th and 19th centuries, garrisons depended on women to make Soldiers' lives tolerable. Some found employment with officers' families or as mess cooks. Women employed as laundresses, cooks, or nurses were subject to the Army's rules of conduct.

Women also served as spies during the Revolutionary War. The war was fought on farms and in the backyards of American families across the width and breadth of the colonies and along the frontier. Women took an active role in alerting American troops to enemy movement, carried messages, and even transported contraband.

More than 400 women disguised themselves as men and fought in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War.

During the Civil War, women stepped into many nontraditional roles for the time. Many women supported the war effort as nurses and aides, while others took a more upfront approach and secretly enlisted in the Army or served as spies and smugglers. Women were forced to adapt to the vast social changes affecting the nation, and their ability and willingness to assume these new roles helped shape the United States.

More than 400 women disguised themselves as men and fought in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War.

Thousands of women got caught up in the nation's struggle between the North and South and assumed new responsibilities at home, and on the battlefield. Many took care of farms and families while encouraging and supporting the war effort, while others served Soldiers more directly as nurses, cooks, laundresses and clerks.

Nurses served in the hospitals of both the Union and Confederate Armies, often also performing their humanitarian service close to the fighting front or on the battlefields themselves – earning the undying respect and gratitude from those whom they served. About 6,000 women performed nursing duties for the federal forces. It is estimated that approximately 181 Black nurses served in convalescent and U.S. government hospitals during the war.

Although forbidden to join the military at the time, over 400 women still served as secret Soldiers in the Civil War. It was relatively easy for them to pass through the recruiter's station, since few questions were asked – as long as one looked the part. Women bound their breasts when necessary, padded the waists of their trousers, cut their hair short, and even adopted masculine names.

As regiments faced the reality of war, some women rallied Soldiers to fight, bearing the regimental colors on the march, or even participating in battle. "Daughters of the Regiment," as they were commonly referred to, were part of some Civil War units. This title probably originated to designate an honorary "guardian angel," or nurse.

With the Spanish-American War came an epidemic of typhoid fever and a need for highly qualified Army nurses. The surgeon general requested and promptly received congressional authority on April 28, 1898. Due to the exemplary performance of these Army contract nurses, the U.S. military realized that it would be helpful to have a corps of trained nurses, familiar with military ways, on call. This led the Army to establish a permanent Nurse Corps in 1901.

Military nursing had been almost dormant since the Civil War. This profession required a high level of competence, and military nurses became known as "contract nurses" of the Army. Between 1898 and 1901, more than 1,500 women nurses signed governmental contracts and served in the United States, Puerto Rico, the Philippine Islands, Hawaii, China, Japan and on the hospital ship Relief.

Nurses serve aboard the U.S. Army Hospital Ship Relief in Cuban waters in 1898. The ship was renamed the USS Relief in 1908 and served until 1919. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Women's Museum)

The selfless service of Army nurses during the Spanish-American War was acknowledged by the Army when they established the Nurses Corps as a permanent corps of the Medical Department, under the Army Reorganization Act of 1901. Nurses were appointed to the Regular Army for a three-year period, although nurses were not actually commissioned as officers in the Regular Army during that period of time. The appointment could be renewed provided the applicant had a "satisfactory record for efficiency, conduct and health."

The law directed the surgeon general to maintain a list of qualified nurses who were willing to serve in an emergency. Therefore, provisions were made to appoint a certain number of nurses with at least six months of satisfactory service in the Army on a reserve status. This was the first Reserve Corps authorized in the Army Medical Department, and the first ever Reserve Corps of women.

More than 35,000 American women served in the military during World War I.

Upwards of 25,000 American women between the ages of 21 and 69 served overseas during World War I. They began going in August of 1914 — at first individually or with a few companions, later with service organizations, and lastly at the request of the U.S. government. Although the largest number were nurses, women served in numerous other capacities – from administrators and secretaries to telephone operators and architects. Many women continued to serve long after Armistice Day, some returning home as late as 1923. Their efforts and contributions in the Great War left a lasting legacy that inspired change across the nation. The service of these women helped propel the passage of the 19th Amendment, June 4, 1919, guaranteeing women the right to vote.

More than 35,000 American women served in the military during World War I.

The National Service School was organized by the Women's Naval Service in 1916 to train women for duties in time of war and national disasters. The Army, Navy and the Marine Corps cooperated to train thousands of women for national service. Skills taught included: military calisthenics and drill, land telegraphy or telephone operating, manufacturing surgical dressings and bandages, signal work and many more.

When the U.S. government declared war on Germany in the spring of 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act requiring the registration of all males between the ages of 20 and 30. American Women quickly felt the impact of the nation's decision to go to war, after roughly 16 percent of the male workforce trooped off to battle.

The call went out to women to fill the vacancies in shops, factories and offices throughout the country. Eventually 20 percent or more of all workers in the wartime manufacture of electrical machinery, airplanes, and food were women. At the same time, they dominated formerly masculine jobs as clerical workers, interpreters and telephone operators, typists and stenographers. Women also occupied work as physicians, dentists, dietitians, pathologists, occupational and physical therapists, administrators, secretaries, "chauffeuses," searchers (for Soldiers listed as missing), statisticians, decoders, librarians, supervisors of homes for women munitions workers, recreation directors, accountants, social workers, journalists, peace activists, small factory and warehouse operators, laboratory technicians, and architects. Such skills, along with nursing, would be needed both on the homefront and at the fighting front in the "War to End All Wars."

Army nurses were sent to Europe to support the American Expeditionary Forces. Training with gas masks was mandatory for all women serving in France in WWI. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Women's Museum)

SPOTLIGHT CONTRIBUTORS

More than half of the women who served in the U.S. armed forces in World War I – roughly 21,000 – belonged to the Army Nurse Corps.

More than half of the women who served in the U.S. armed forces in World War I – roughly 21,000 – belonged to the Army Nurse Corps, and performed heroic service in camp and station hospitals at home and abroad.

When the U.S. entered World War I, there were only 403 nurses on active duty, and the need for nurses continued to grow. These nurses found themselves working close to or at the front, living in bunkers and makeshift tents with few comforts. They experienced all the horror of sustained artillery barrages and the debilitating effects of mustard gas.

The Nurse Corps was redesignated the Army Nurse Corps by the Army Reorganization Act of 1918. Army nurses did not have officer status and were appointed without commission. After the war, Congress gave nurses officer status, but with "relative rank," which meant that a nurse lieutenant received less pay and status than a male lieutenant.

Army nurses also played a critical role in the worldwide influenza epidemic of 1918, one of the most deadly epidemics in modern times. An estimated 18 million people around the globe lost their lives; among those were more than 200 Army nurses.

SPOTLIGHT CONTRIBUTORS

The U.S. Army Signal Corps recruited and trained more than 220 women - best known as the "Hello Girls" - to serve overseas as bilingual telephone operators.

The U.S. Army Signal Corps recruited and trained more than 220 women - best known as the "Hello Girls" - to serve overseas as bilingual French-speaking telephone operators.

The Army Signal Corps women traveled and lived under Army orders from the date of their acceptance until their termination from service. Their travel orders and per diem allowance orders read "same as Army nurses in Army regulations." They were required to purchase uniforms designed by the Army - with Army insignia and buttons.

When the war ended and the telephone operators were no longer needed, the Army unceremoniously hustled the women home and refused to grant them official discharges, claiming that they had never officially been "in" the service. The women believed differently, however, and for years pressured Congress to recognize their services. Finally, after considerable congressional debate, the Signal Corps telephone operators of World War I were granted military status in 1979 - years after the majority of them had passed away.

SPOTLIGHT CONTRIBUTORS

Women served in large numbers in civilian welfare organizations both at home and abroad, including the American Red Cross, YMCA, and Salvation Army.

Women served in large numbers in civilian welfare organizations both at home and abroad. The largest of these organizations were the American Red Cross, the Young Men's Christian Association, and the Salvation Army.

By far the largest American organization overseas was the ARC. The number of volunteers with the ARC rose from 20 in 1914 to 6,000 women and men in January 1919. The ARC mainly focused on hospitals and civilian/refugee relief, though it served Soldiers and civilians in almost every conceivable way.

By order of the U.S. Army, the YMCA bore the major responsibility for the welfare of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). It was to "provide for the amusement and recreation of the troops by means of its usual program of social, educational, physical, and religious activities." The YMCA ran hundreds of canteens, recreational huts where Soldiers could write letters, sing songs, play games, and buy snacks or cigarettes. The YMCA ultimately employed about 3,500 women, approximately one-fifth of its total workforce.

Although the SA was tiny compared to the ARC and YMCA, it was arguably the most loved by Soldiers. Only about 250 Salvationists served overseas, and were unique in that they often followed Soldiers to the front lines. The SA remained loyal to its slogan of "Soup, Soap, and Salvation," which came in the form of its now-famous doughnuts and other homemade goods, money transfer services, the mending of clothes and religious services. Even with the SA's Christian tenets, its canteens and services were available to all.

Although the idea of women in the Army other than the Army Nurse Corps was not completely abandoned following World War I, it was not until the threat of world war loomed again that renewed interest was given to this issue. With the rumblings of World War II on the horizon, Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts states, "I was resolved that our women would not again serve with the Army without the same protection the men got." As a result, the creation of the Women’s Army Corps was one of the most consequential gender-based events in American history.

Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) were the first brave women to fly American military aircraft. They forever changed the role of women in aviation.

Women stepped up to perform an array of critical Army jobs in order "to free a man to fight." They worked in hundreds of fields such as military intelligence, cryptography, parachute rigging, maintenance and supply, to name a few. Additionally, more than 60,000 Army Nurses served around the world and over 1,000 women flew aircraft for the Women's Airforce Service Pilots. Through the course of the war, 140,000 women served in the U.S. Army and the Women's Army Corps, proving themselves vital to the war effort. The selfless sacrifice of these brave women ushered in new economic and social changes that would forever alter the role of women in American society.

Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) were the first brave women to fly American military aircraft. They forever changed the role of women in aviation.

The period immediately following World War II was one of uncertainty and constant change for Women's Army Corps personnel. The original intent of the WAC was to last for the duration of the war plus 6 months. However, this post-war period also marked great strides for integrating both the WAC and the Army Nurse Corps into the Regular Army.

Immediately following World War II, demobilization of WAC personnel progressed rapidly. Some WACs remained on active duty both in the continental United States and with the Armies of Occupation in Europe and the Far East, while others decided to return home with their memories and souvenirs from the war. In August 1945, enlistments in WAC closed with the Corps' schools and training centers also closed.

Signal Office telephone center for the Far East Air Forces headquarters near Manila, Philippines, 1945. This was a six-place board, where WACs on duty operated complicated telephone connections for Army units. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Women's Museum)

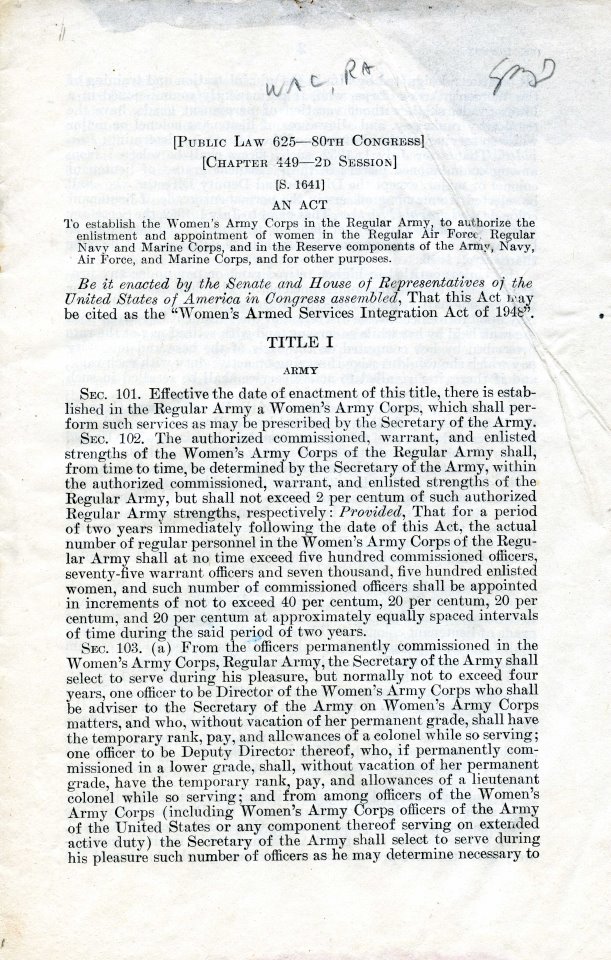

Due to the exceptional service of military women during World War II, the Women's Armed Service Integration Act was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman on June 12, 1948. This bill enabled a permanent presence of women in the military, including WAC, WAVE, women in the Marine Corps, and women in the Air Force. It also created for the first time an organized Reserve for each of these branches.

was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman on June 12, 1948. This bill enabled a permanent presence of women in the military, including WAC, WAVE, women in the Marine Corps, and women in the Air Force. It also created for the first time an organized Reserve for each of these branches.

One month after the passage of the act, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, establishing equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed services, paving the way for the racial desegregation of the Army. These two policies came to realization at Camp Lee, Virginia, where the first training center for the permanent WAC was opened on Oct. 4, 1948. The WAC Training Center was commanded, staffed, and operated entirely by women. Over 30,000 women trained at Camp Lee before it was moved to a new location at Fort McClellan in 1954.

The first WAC Organized Reserve Corps training was initiated on June 15, 1949. To obtain more WAC officers, the first direct commissions were offered that year to women college graduates as second lieutenants in the Organized Reserve Corps.

Similar to WAC, the Army Nurse Corps also made strides toward integration into the Regular Army during the post-World War II era. On April 16, 1947, President Harry S. Truman signed Public Law 80-36, the Army-Navy Nurses Act of 194, which established the Women's Medical Specialist Corps and the Army Nurse Corps as part of the Regular Army. The act also provided permanent commissioned officer status to military nurses, which put an end to relative rank and the full-but-temporary ranks granted during the middle of the war.

President Harry S. Truman ordered U.S. air and naval forces into the Republic of Korea on June 27, 1950. With the outbreak of the Korean conflict, WAC strength authorization increased. WAC officers were involuntarily recalled to active duty, and those who had been the first to enlist when the Women's Armed Services Integration Act passed in 1948 were caught in involuntary extensions. This was the first time women were summoned to active duty without their consent.

Although a WAC unit was not established in Korea, thousands of WACs served in the Pacific theater during the Korean War. Many were sent on assignment individually to the Korean Peninsula. The Korean Women's Army Corps was formed in 1950, around a group of policewomen trained by a former WAC, Alice A. Parrish. In 1952, a number of individual WAC officers and enlisted women filled key administrative positions in Pusan and later in Seoul. WACs were also sent to Cold War Europe and worked mainly as cryptographers; supply, intelligence, and communication specialists; and hospital technicians.

WACs at Camp Lee train in various fields. Preparing for the completion of their work, these women pose for a quick photo. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Women's Museum)

During the Korean War, over 25,000 WACs and 5,000 nurses served in the Army.

Just like during World War II, Army nurses served in the combat theater very close to the extremely fluid front lines of the war. As a rule, they were the only military women allowed into the combat theater during this war. Nurses served in Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals, or MASH, field hospitals, hospital trains, and – during the early weeks of the war – on Army transport ships.

During the Korean War, over 25,000 WACs and 5,000 nurses served in the Army.

After the Korean War, and with the move of the WAC Training Center and School to Fort McClellan, Alabama, the focus of the Corps shifted to the examination of management practices and the image of the WAC. The WAC directors in the 1950s and 1960s sought to expand WAC by increasing the types of jobs available in the Army, and by promoting the Corps not only to possible recruits, but also to their family members. The leadership worked hard to act as role models and to instruct the women to respect the Corps, take pride in their work, and ensure that their personal behavior and appearance was always above reproach. Their success was marked by a request from the Army chief of staff to lift the recruitment ceiling on the number of women. It was also during this era that we see the removal of restrictions on promotions, assignments and utilization.

In 1954, the Army established a permanent home for the WAC at Fort McClellan, Alabama, and all WAC activities at Fort Lee, Virginia, discontinued on Aug. 15. The center included a headquarters, a basic training battalion and a Women's Army Corps School.

Not long after the establishment of the training center, the Army Uniform Board approved the concept of two green uniforms for women. The first was the Army green cord suit, issued in March 1959, followed by the Army green service uniform, issued in July 1960. The development of the Army green uniform for both men and women marked another move toward equality between men and women Soldiers.

Women did not serve in the Vietnam War until nearly a decade after U.S. involvement. The first WAC officer was assigned to Vietnam in March 1962, but it was not until 1965 that the use of WAC personnel in support elements was considered feasible for Vietnam. It was decided that WACs could make positive contributions, particularly in clerical, secretarial and administrative military occupational specialties (MOS). The initial mission for Army women was to train Vietnamese army women. Later, in 1967, the Vietnam WAC Detachment was activated at Long Binh. Hundreds of other WACs were assigned to individual headquarters in theater. WACs continued to serve in Vietnam until the withdrawal of troops in 1973.

By the end of the war, over 800 WACs had served in theater. More than 9,000 Army nurses served in hospitals and medical clinics throughout Vietnam.

Similarly, Army nurses were dispatched to support the fighting forces in April 1965, with the rapid buildup of American forces in Vietnam. Between 1966 and 1972, thousands of Army nurses served in combat theater, very close to combat. The last of more than 5,000 nurses departed from the Republic of Vietnam two months after the cease-fire, March 29, 1973.

By the end of the war, over 800 WACs had served in theater. More than 9,000 Army nurses served in hospitals and medical clinics throughout Vietnam.

Public Law 90-130, signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on Nov. 8, 1967, removed promotion and retirement restrictions on women officers in the armed forces. Thereafter, it was possible for more than one woman in each service to hold the rank of colonel and for women to achieve general (or flag) officer rank.

Just two years later, President Richard M. Nixon selected two women for promotion to brigadier general: Col. Anna Mae Hays, chief of the Army Nurse Corps, and Col. Elizabeth P. Hoisington, director of the Women's Army Corps. These promotions were done simultaneously on June 11, 1970, in recognition of their equal importance.

PL 90-130 also eliminated the two percent limitation on WAC numbers – permitting WACs to serve in the Army National Guard. At this point, only prior-service women were allowed to join, due to the war in Vietnam demanding so much money that none was available to train women for enlisted Guard service.

As the war in Vietnam drew to a close and the Army began transitioning to an all-volunteer force, the role of women in the Army expanded to help fill vacancies before the draft ended in June 1973. In 1971, women with no prior-service experience were permitted to enlist in the National Guard. When estimates for male recruits revealed a looming shortfall in volunteers, Secretary of the Army Robert F. Froehlke approved a major expansion in WAC strength and the opening of all military occupational specialties to women in August 1972, except those that might require combat training or duty. This was the realization that women could be utilized in far greater capacity than ever before. That same year, the ban on women commanding units that included men was lifted.

This time period also marked the beginning of other advancements for women. Army regulations for the first time permitted women to request waivers for retention on active duty if married and pregnant, April 9, 1971. In that same year, the Army chief of staff authorized WACs' entry into male drill sergeant schools and NCO academy programs.

The parachute rigger MOS had been open to women since World War II, but they were not "jump-qualified." However, the opening of all MOSs changed that, and women quickly began graduating from the parachute riggers course, assigned to Airborne units around the country, and were jumping with their own chutes.

The Vietnam War, the elimination of the draft, and the rise of the feminist movement had a major impact on both the Women's Army Corps and Army Nurse Corps. There was a renewed emphasis on parity and increased opportunity for women in uniform.

The advent of the all-volunteer force in 1973 made a large difference in the numbers of women coming into the Army and Reserve components. As a result of recruitment, training and greater opportunities, the total number of WACs in the Army increased from 12,260 in 1972 to 52,900 in 1978.

Women entered the Army Reserve Officers Training Program (ROTC) beginning in September 1972, and the first female ROTC cadets graduated from South Dakota State University on May 1, 1976. Prior to this, the primary source of commissioning was the Junior College Women's Program.

In 1975, the Army chief of staff approved the consolidation of basic training for men and women when test programs showed that "female graduates met the standards in every area except the Physical Readiness Training Program," which could be modified without compromising the value of training. By 1977, combined basic training for men and women became policy, and men and women began integrating in the same basic training units on Fort McClellan, Alabama and Fort Jackson, South Carolina, in September. Similarly, the first gender-integrated class began with the Military Police One-Station-Unit Training at Fort McClellan on July 8, 1977.

Between 1975 and 1979, many Army rules and regulations concerning women changed and the standards for men and women in the Army began to equalize. The defense secretary directed the elimination of involuntary discharge of military women because of pregnancy and parenthood, June 30, 1975. Mandatory defensive weapons training was initiated for enlisted women and they were authorized to serve the same length of overseas tours as men – increased from 24 months to 36 months for single females. Effective April 1, 1976, the minimum age of enlistment of women was reduced to the same as for men, and by October 1979, all enlistment qualifications became the same for men and women.

Another major advancement for equal standards between men and women in the Army came in October 1975, when President Gerald Ford signed Public Law 94-106 that permitted women to be admitted to all service academies beginning in 1976. In 1980, the first women cadets graduated from U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York. Since then, women have continued to enter every class there.

The need for a separate Women's Army Corps faded as women assimilated into male training, assignments, and logistics and administrative management. In September 1978, Congress passed Public Law 95-584 that disestablished the WAC as a separate Corps of the Army, effective Oct. 20, 1978.

The disestablishment of the WAC and the integration of women into the Regular Army paved the way for women to continue breaking down gender barriers. In the ensuing years, the Army was called upon to respond to regional conflicts, natural disasters and humanitarian crises around the globe. The roles of Army Women were tested and redefined during these contingency operations.

Operation Urgent Fury in Grenada proved to be the Army's first test of the new assignment policy since the disestablishment of the WAC. U.S. forces were ordered to Grenada to rescue Americans. Four female military police officers were in Grenada just after the U.S. invasion, but were promptly sent back to their base in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Oct. 25, 1983. A day and a half later, they were returned to Grenada by the XVIII Corps commander. Despite initial confusion about the deployment of women to an active combat zone, over 100 women eventually participated in the mission. In the decades to follow, policies implemented to resolve the issue of women in combat continuously evolved to reflect a changing battlefield.

In December 1988, the Secretary of Defense issued the Standard Risk Rule to help standardize the services' assignment of women to hostile areas. The first test to this Risk Rule was faced in Panama during Operation Just Cause in December 1989. Over 600 Army women participated in the operation to restore the democratically elected government and arrest drug czar and dictator, Manuel Noriega. Women were stationed in Panama prior to hostilities breaking out. Suddenly, their roles proved critical in the middle of this combat zone and the Army found itself with a female military police commander, Capt. Linda Bray, commanding men in battle for the first time.

In the largest call up of women since World War II, over 24,000 women served in the Persian Gulf War, beginning in 1990. During Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, the focus was on the mission more than the gender of the troops. With the call up of Reserves, which was filled with women, the Army utilized women to their fullest potential. After the conflict, military leaders acknowledged that excluding women from the mission would have impacted combat readiness.

Coming on the heels of Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, the Department of Defense continued its effort to respond to challenges with changing missions and the assignment of women. In July 1994, Secretary of Defense Les Aspin rescinded the 1988 Risk Rule and issued a new "Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule," directing that women were eligible to be assigned to all positions for which they qualified, except for units below brigade level whose primary mission is to engage the enemy in direct combat.

In Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo, women were trained to cope with food riots, terrorist attacks, ethnic and clan conflicts, and peacekeeping. Their roles continued to be tested during these operations, although there seemed to be few questions about what women could or could not do and the value they added to the Army's mission.

The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 marked a pivotal changing point for Army women. As the Army's mission changed on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan, so did the roles of women in its ranks. With the Global War on Terror campaign, there was a rapid expansion of jobs and change in roles for Army women. Beginning In 2016, women have the equal right to choose any military occupational specialty, including ground combat units, that were previously unauthorized.

One significant female contribution was recognized on June 16, 2005, when Sgt. Leigh Ann Hester was awarded the Silver Star for her actions during a firefight that took place outside Baghdad. This was the first Silver Star in U.S. military history awarded to a female Soldier for direct combat action.

Another major impact of women came in 2010 when the Army began utilizing Female Engagement Teams (FET) and Combat Support Teams (CST) in Afghanistan. The primary task of these teams was to engage female populations where such engagement was not possible by male service members. The FET and CST teams performed a number of duties, including intelligence gathering, relationship building, and humanitarian efforts.

The role of women in combat positions has been debated throughout American history, even though women have been on the "frontlines" since the Revolutionary War. In 2013, Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta signed a document to lift the Defense Department's ban on women in direct ground combat roles. This historical decision overturned the 1994 Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule that restricted women from Artillery, Armor, Infantry, and other combat roles and military occupational specialties.

Just two years later, on Dec. 3, 2015, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter directed the full integration of women in the armed forces following a 30-day review period required by Congress, which was completed April 7. Beginning in January 2016, all military occupations and positions opened to women, without exception. For the first time in U.S. military history, as long as they qualified and met specific standards, women were able to contribute to the Department of Defense mission with no barriers in their way.