- The Army in the field, known as the line as opposed to the

- [3]

- staff in the War Department, was organized in tactical units and stationed

at posts throughout the country. The regiment was normally the largest unit

and was often scattered over a large area. The posts were grouped geographically

into "departments" commanded by officers in the rank of colonel

or higher. Above the geographical departments in the field the chain of command

was confused and, in fact, fragmented. The titular military head of the line

Army was the Commanding General, a position created by Secretary Calhoun but

without Congressional authorization prescribing its duties and functions or

defining its relations with the bureaus, the Secretary, and the President.

-

- The Commanding General did not in fact or in law command the Army. Successive

incumbents asserted repeatedly that in a proper military organization authority

should be centralized in one individual through a direct, vertical, integrated

chain of command. Instead the bureau chiefs in Washington were constantly

dealing directly with their own officers in the field at all levels of command,

acting they insisted under the authority and direction of the Secretary of

War. When the Commanding General protested such actions as violating the military

principle of "unity of command," the Secretary of War generally

supported the bureau chiefs.

-

- The President was constitutionally the Commander in Chief, and many including

James Madison, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Abraham Lincoln at times

exercised their command personally or through the Secretary of War rather

than the Commanding General. By the end of the Civil War Lincoln had established

unity of command in the field under General Ulysses S. Grant, but the extent

of the latter's control over the bureaus was not clear, and, in any case,

after the war the old system of divided control was revived.2

-

- As prescribed formally in Army regulations the division of functions seemed

reasonably clear. All orders and instructions from the President or the Secretary

of War relating to military operations, control, or discipline were to be

promulgated through the Commanding General. On the other hand, fiscal

- [4]

- affairs were to be conducted by the Secretary of War through the several

staff departments:

-

- The supply, payment, and recruitment of the Army and the direction of the

expenditures of appropriations for its support, are by law entrusted to the

Secretary of War. He exercises control through the bureaus of the War Department.

He determines where and how particular supplies shall be purchased, delivered,

inspected, stored and distributed.3

-

- This theoretical clarity did not exist in practice. An informal alliance

developed between the civilian secretaries and the bureau chiefs which hamstrung

the Commanding General's control over the Army. The departmental staff's responsibility

for logistics and support also diluted his authority over the territorial

departments. Several commanding generals in protest moved their headquarters

from Washington. Since secretaries came and went, power gravitated to the

bureau chiefs, who, in the absence of any retirement system, remained in office

for life or until they resigned.

-

- The secretaries were unable as a consequence to exercise any effective control

over the bureau chiefs upon whom they had to rely for information. The bureaus

operated as virtually independent agencies within their spheres of interest.

These spheres often overlapped and conflicted, demonstrating what Roscoe Pound,

dean of the Harvard Law School, described as "our settled American habit

of non-cooperation.4

The whole system was sanctioned and regulated in

the minutest detail also by Congressional legislation, and any changes almost

invariably involved Congressional action. Bureau chiefs in office for life

also had greater Congressional influence than passing secretaries or line

officers.

-

- In effect, the War Department was little more than a hydra-headed holding

company, an arrangement industrialists were finding increasingly wasteful

and inefficient.5

- [5]

- One War Department committee seeking means of improving its methods of operation

concluded:

-

- The fundamental trouble was in the system of administration a system that

was the gradual growth of many years, and founded upon the idea that the bureau

chiefs in Washington and the Secretary of War were the only ones who could

be trusted to decide either important or trivial matters in a manner to properly

protect the interests of the Government; a system that necessarily resulted

in congesting the paper work in Washington, in multiplying the number of clerks

required to handle and record the papers, and finally in so overloading

the chiefs of bureaus . . . by attention to unimportant details, that they

had not sufficient time for the consideration of more important matters. 6

-

- This legacy of bureau autonomy and Congressional control in managing the

affairs of the Army and the War Department was passed on from the nineteenth

century to the twentieth and constituted a principal problem of Army organization.

-

-

- When Elihu Root became Secretary of War on 1 August 1899 the moment was

opportune to assert greater executive control over the War Department's operations.

During the Spanish-American War the absence of any planning and preparation,

the lack of co-ordination and co-operation among the bureaus, and the delay

caused by red tape had become a public scandal.

-

- President William McKinley appointed a commission headed by retired Maj.

Gen. (of Volunteers) Grenville M. Dodge, a Civil War veteran and railroad

promoter, to investigate the problem. After intensive hearings and investigation

the Dodge Commission reported that most of the trouble stemmed from the red

tape and inefficiency of the War Department's operations generally and in

the Quartermaster's and Medical Departments in particular. Congress, it said,

was partially to blame because of its insistence upon monitoring departmental

administration in detail. Everywhere officials were forced by regulations

spawned in Congress to devote too much

- [6]

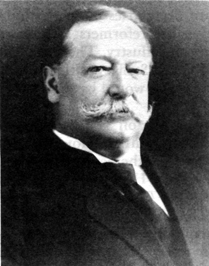

- SECRETARY ROOT

-

- time to paper work and not enough to substantive matters. "No well

regulated concern or corporation could transact business satisfactorily under

such regulations as govern the staff departments." The commission particularly

recommended investigating the question of combining all supply operations

in one agency and transportation in another, following the example of modern

industrial organizations. 7

-

- After studying the Dodge Commission report, Secretary Root told Congress

that unless drastic changes were made in War Department organization and administration

to provide for greater executive control the department would be unable to

operate effectively in any war. It would break down again,

- [7]

- and in its place a "jury-rigged, extempore" organization would

be thrown together on an emergency basis. As a corporation lawyer he asserted

that "in the successful business world" work was not done in the

disorganized manner of the War Department. "What would become of a railroad,

or a steel corporation, or any great business concern if it should divide

its business in that way? What would become of that business?" 8

-

- A modern army, Mr. Root said, required intelligent planning for possible

future military operations and effective executive control over current ones.

Intelligent planning required an agency similar to the General Board of the

Navy or the Great German General Staff. Control over current operations required

a professional military adviser to act as the department's general manager

with a staff to assist him along the lines of modern industrial corporations.

Mr. Root proposed that Congress provide by law for a Chief of Staff as general

manager with a General Staff which would assist him both in planning future

operations and in supervising and co-ordinating current ones.

-

- Mr. Root's proposal represented a major break with War Department tradition.

He was the first Secretary of War to abandon the alliance between the Secretary

and the bureau chiefs, replacing it by an alliance with line officers through

the Office of the Chief of Staff. The alliance was deliberate because Root

did not see how it was possible for any Secretary to exercise effective control

over the department unless he had the active support of professional soldiers

whose interests, expressed in terms of their traditional insistence on unity

of command, were similar. 9

-

- To achieve these goals Mr. Root first had to abolish the

- [8]

- position of Commanding General. He made it clear to Congress that the Chief

of Staff would act under the authority and direction of the Secretary of War

and the President as constitutional Commander in Chief. He would not "command"

the Army or be designated as the Commanding General because command implied

an authority independent of the Secretary and the President. This change in

title would avoid the repeated conflicts that had arisen between successive

commanding generals and the Secretary or the President during the previous

century. At the same time he wanted the Chief of Staff to be the principal

military adviser of the Secretary and President. There was under the Constitution

only one Commander in Chief, the President, acting through the Secretary of

War, and there should be only one principal military adviser for the Army,

the Chief of Staff, to whom all other Army officers would be subordinate. 10

-

- The need for firm executive control over the bureaus, Mr. Root told Congress,

was obvious. The bureaus overlapped and duplicated one another's functions

up and down the line. Their traditional mutual antagonism caused disagreements,

no matter how petty, to come all the way up to the Secretary personally for

resolution. Supplying electricity for new coastal defense fortifications provided

a glaring example. In those days, fifty years before anyone ever heard of

project management, at least five overlapping bureaus were involved in supplying

some part of the electricity needed to build or operate the fortifications,

the Engineers in construction, the Quartermaster for lighting the posts, the

Signal Corps for communications, the Ordnance for ammunition hoists, and the

Artillery which had to use the guns. If the Secretary acted on the request

of one bureau, the others immediately complained of interference with their

work. The only thing he could do was to call in the bureau chiefs concerned

and spend half a day thrashing out a decision. The Secretary simply could

not spend all his time on such details, and the result was that the bureaus

were continually stepping on each other's toes. 11

-

- In Mr. Root's scheme the Chief of Staff, assisted by the

- [9]

- General Staff, would investigate and recommend to the Secretary solutions

to such technical problems. Root further recommended consolidating all Army

supply operations in one bureau along the lines suggested by the Dodge Commission.

This was the way modern industrial corporations did business, and it did seem

a pity, he thought, "that the Government of the United States should

be the only great industrial establishment that could not profit" from

the lessons and experiences of modern industry. 12

-

- Mr. Root's proposal to combine responsibility for both current and future

operations in the General Staff created serious management problems from the

start. Neither the General Board of the Navy nor the German General Staff,

which he cited as examples of what he had in mind, had administrative responsibilities.

In the government as well as in industry responsibility for current operations

has always tended to drive future planning into the background. Co-ordinating

bureau activities also involved the General Staff in bureau administration,

especially where the bureaus came into conflict with one another as they frequently

did. In practice the distinction between supervision or co-ordinating and

direction or administration was largely theoretical. What was supervision

to the General Staff the bureaus objected to as interfering with their traditional

autonomy. They also naturally resented their proposed subordination to the

Chief of Staff which would remove them from their traditional direct access

to the Secretary.

-

- A study of just this question of divided authority over and among the bureaus

was the subject of a lengthy, penetrating analysis by the War Plans Division

of the War Department General Staff submitted on 28 February 1919. It noted

how the British and German practice was to keep the planning functions of

the General Staff completely separate from administration. It asserted that

before 1903 there were two distinct weaknesses in the War Department, "the

lack of a powerful permanent coordinating head," solved by creating the

Office of the Chief of Staff, and "the lack of a sufficient number of

- [10]

- properly delimitated administrative services" organized to perform

one function only. As Mr. Root's own experience indicates, the overlap and

duplication of functions among the traditional bureaus had the effect of forcing

the General Staff into administrative details because there was no other agency,

short of the Chief of Staff or the Secretary of War, to resolve the recurrent

conflicts among the bureaus over even the pettiest of details. If there was

any fault in the General Staff becoming involved in administration it was

because the bureaus refused to agree among themselves. The General Staff in

the latter part of World War I attempted just such a functional division of

labor among the bureaus. 13

-

- Mr. Root's own actions demonstrated the difficulty of trying to distinguish

between these two functions. So urgent in his opinion was the need to control

and co-ordinate bureau operations that he did not wait for Congress to provide

for a permanent organization. In 1901 he appointed an ad hoc War College Board

to develop plans, theoretically, for an Army War College, which actually acted

as an embryonic General Staff. Its members spent most of their time assisting

Root in co-ordinating current operations and little on planning. 14

-

- Accepting Mr. Root's recommendations, Congress in the Act of 14 February

1903 provided for a Chief of Staff assisted by a General Staff, but it did

not consolidate the supply bureaus. The General Staff itself, as initially

organized, consisted of three committees designated as divisions, the first

charged generally with administration, the second with military intelligence

and information, and the third with various planning functions.

- [11]

- Then in November 1903 Mr. Root established the Army War College. Its main

function was to train officers for General Staff duties on the principle of

learning by doing as part of a general reformation of the Army's school system.

In practice learning by doing meant that instead of becoming exclusively an

academic institution the War College became part of the General Staff, concentrating

on military intelligence, Congressional liaison, and war planning. That left

the rest of the General Staff to supervise the bureaus.

-

- Students at the War College prepared most of the Army's war plans. They

were geared closely to current contingency and operational requirements, including

the occupation of Cuba in 1906-09, the Japanese war scare arising from the

1907 San Francisco School Crisis, and President Wilson's various Mexican forays.

There was none of the high-level, long-range strategic thinking and planning

which the War College's opposite number, the General Board of the Navy,

performed. 15

-

-

- The new Chief of Staff and the General Staff were immediately attacked by

traditionalists in the bureaus who were opposed to any attempts to assert

control over their autonomy.

- [12]

- The question was whether future Secretaries of War would support the bureaus

or the rationalist reformers seeking to modernize the Army along the lines

of industry. The President or Congress could undercut the Chief of Staff's

position, but it was the Secretary in the first instance who would have to

decide what position to take.

-

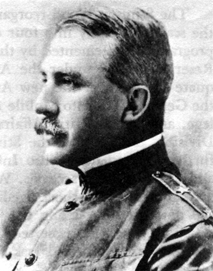

- Mr. Root resigned as Secretary of War on 31 January 1904 with his work unfinished.

His successor, William Howard Taft, lacked the inclination and ability to

make the new dispensation stick in the face of bureau opposition. He was distressed

at having to referee disputes between the Chief of Staff and the bureau chiefs,

particularly Maj. Gen. Fred C. Ainsworth, the new Military Secretary and subsequently

The Adjutant General. "The Military Secretary in many respects is the

right hand of the Chief of Staff," Taft vainly pleaded, "and they

must be in harmony, or else life for the Secretaries and all others in the

Department becomes intolerable. Let us have peace, gentlemen." 16

-

- Under the influence of Ainsworth, Taft abandoned Mr. Root's alliance with

the Chief of Staff for the traditional Secretary-bureau chief alliance. Convinced

the Chief of Staff and General Staff were too involved in administrative details,

he restricted the General Staff's activities in April 1906 to purely "military"

matters. On "civil" affairs the bureau chiefs were to report directly

to the Secretary. It was Taft's belief that the Chief of Staff was Chief of

the General Staff only and served in a purely advisory capacity.

-

- At about the same time President Theodore Roosevelt designated the Military

Secretary (later The Adjutant General) as Acting Secretary of War in the absence

of the Secretary or Assistant Secretary. Taft was frequently absent for long

periods on political junkets, leaving Ainsworth in charge. The Chief of Staff

thus became subordinate to The Adjutant General instead of the reverse as

Mr. Root had intended and as the law clearly stated. 17

-

- All this changed when Henry L. Stimson, a law partner and

- [13]

|

|

| SECRETARY TAFT |

GENERAL AINSWORTH |

-

- protégé of Mr. Root's, became Secretary of War on 22 May 1911. Taking up

where Root had left off, he reasserted the principle of executive control

and embarked on an ambitious program to rationalize the Army's organization

from the top down along sound military and business lines. He reformed Mr.

Root's alliance with the Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, who thought

along the same lines.

-

- General Wood, the Army's first effective Chief of Staff, had been in office

a year when Stimson became Secretary. He was a brilliant administrator with

a much broader background in managing large-scale, multipurpose organizations

than his predecessors or immediate successors. He could distinguish between

the important and the unimportant. Wood could make prompt decisions. He knew

how to select competent subordinates, and he freely delegated authority to

them. He abolished the "committee system" within the General Staff,

eliminating one source of delay. Wherever possible he sought to streamline

departmental procedures in the interests of greater efficiency. He also

made enemies, especially in Congress.18

- [14]

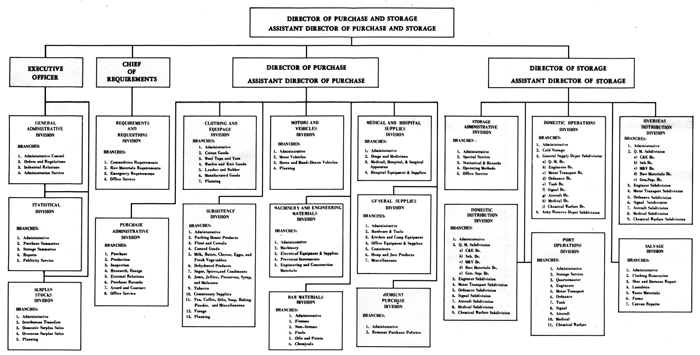

- The Stimson-Wood reorganization called for consolidating the scattered Army

into four divisions with uniform training programs, supplemented by the National

Guard and an Army Reserve directly under the Army's control. To provide adequate

control over the new Army General Wood reorganized the General Staff into

Mobile Army, Coast Artillery, War College, and later Militia Affairs Divisions.

The Mobile Army Division, the heart of the Stimson-Wood reorganization, was

further broken down into Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery, and Miscellaneous

sections. When Mr. Stimson left office he was able to send a short five-line

telegram to mobilize one of the new divisions along the Texas border. Under

the "traditional" system, he asserted, he would have had to scrabble

together an improvised task force, sending out fifty to sixty telegrams in

the process. 19

-

- In their reforms Stimson and Wood were simply applying principles employed

by contemporary industrial managers in rationalizing and integrating previously

fragmented, large-scale organizations. These coincided, as mentioned earlier,

with the desire of professional soldiers for unity of command over the department.

They were handicapped because, unlike their industrial counterparts, they

had little control over funds, the ultimate weapon in industrial reorganization,

and they required Congressional action for most of their program.

-

- The 1910 elections returned a Democratic House of Representatives, and the

new chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee, James Hay of Virginia,

was a rural Jeffersonian opposed on principle both to a large standing army

and the idea of a General Staff. From 1911 until his retirement from Congress

in September 1916, Hay did his best to limit the size and activities of the

General Staff with substantial assistance from War Department traditionalists,

chiefly General Ainsworth.

- [15]

|

|

| SECRETARY STIMSON |

GENERAL WOOD |

-

- The principal complaint of the traditionalists was that Wood and the General

Staff continually interfered in strictly administrative details. As Wood told

Congress some years later what often appeared to be an issue of "mere

administrative detail . . . was nothing of the kind." Who was to decide,

for example, how much ammunition should be carried by each artillery caisson?

When the Chiefs of Ordnance and Artillery disagreed, as they often did, the

General Staff had to find some means of resolving the dispute. Mr. Root had

earlier cited similar disagreements which had become frustrating,

time-consuming

daily reality within the War Department. Wood preferred to issue orders rather

than engage in protracted discussions. 20

-

- The ideological gap between Hay and Stimson and between Ainsworth and Wood,

reflected in their opposing views on Army organization, was enormous. In the

face of Congressional opposition, Stimson and Wood were forced to accept half

a loaf as better than none. In their proposed reorganization of the field

army they wished to consolidate Army units scattered about in forty-nine

separate posts, many of them no longer

- [16]

- serving useful military purposes, into eight large posts to facilitate uniform

training and mobilization. Congress vetoed this plan. On the other hand, Congress

approved the long-standing proposal of Army reformers to consolidate the Quartermaster,

Subsistence, and Pay Departments into a single Quartermaster Corps.21

-

- Streamlining the administration of the War Department was one, major area

in which Stimson and Wood were free to assert firm executive control. It was

this program that brought about a direct confrontation between Generals Wood

and Ainsworth. Personalities aside, the immediate issue was who should control

the administration of the department under the Secretary-the Chief of Staff

or The Adjutant General.

-

- Simplifying the department's paper work was a constant problem for the secretaries

and the General Staff. President Roosevelt had asserted that departmental

administration was an executive function. On 2 June 1905 he appointed a commission

headed by Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Charles Hallam Keep to study

and make recommendations on how to improve the "conduct of the executive

business of the government . . . in the light of the best modern business

practices." Among other things he asked particularly that some means

be found to cut back the useless proliferation of paper work in the Army and

the Navy because "the increase of paper work is a serious menace to the

efficiency of fighting officers who are often required by bureaucrats to spend

time in making reports which they should spend in increasing the efficiency

of the battleships or regiments under them." 22

-

- Congress took no action on the Keep Commission report, but it approved the

later appointment by President William Howard Taft of a Committee on Economy

and Efficiency under Dr. Frederick A. Cleveland, a leader in the new field

of public administration, who wished to rationalize public administration

along businesslike lines. The committee concentrated on administrative details.

They "counted the number of electric

- [17]

- bulbs in the Federal Building in Chicago. They counted the number of cuspidors

in the corridors of Federal buildings elsewhere." Such attention to minute

details was customary procedure in this early period when Frederick W. Taylor's

Scientific Management with its time and motion studies was the vogue among

industrial reformers.23

-

- The Cleveland Commission found much to criticize in the War Department's

administration. Among other things, the members thought the muster roll, a

cumbersome service biography in multiple copies for each soldier, should be

abolished and simpler means found to accomplish the same end. Secretary Stimson

and General Wood agreed. General Ainsworth insisted the muster roll was one

of the most vital documents in the Army, leaving the distinct impression that

the Army could not function effectively without it. Forgetting himself, Ainsworth

behaved in such a manner toward General Wood and Secretary Stimson that Mr.

Stimson had no choice but to order him court-martialed for insubordination.

Ainsworth's Congressional supporters persuaded the Secretary to allow him

to retire instead.24

-

- With General Ainsworth gone, Secretary Stimson and later Stimson's successor,

Lindley M. Garrison, were able to carry out a number of the administrative

reforms inspired by the Cleveland Commission. Resistance to abolishing the

muster roll within The Adjutant General's Office led to compromises which

kept the document alive until the huge expansion of the Army during World

War I forced its abandonment. Vertical files were introduced at a great saving

in space and time. Beginning in January 1914, the Dewey decimal classification

was gradually substituted for General Ainsworth's cumbersome, triplicate numerical

files. During this same period the Chief of Ordnance, Brig. Gen. William Crozier,

with Secretary Stimson's support, sought to introduce Taylor's scientific

management principles into Ordnance arsenals. Determined opposition

- [18]

- from labor unions persuaded Congress to prohibit the use of Taylor's time

and motion studies within the Army and Navy and later the entire federal government,

a law which remained on the statute books until 1949.25

-

- General Ainsworth after retirement had not given up his fight against the

General Staff. He had simply shifted the base of his operations to the House

Committee on Military Affairs where James Hay welcomed his assistance as an

unofficial adviser. Secretary Stimson and later Secretary Newton D. Baker

detected what they felt was Ainsworth's influence in seemingly minor but very

hostile provisions of legislation coming from that committee.26

-

- President Taft, urged by Secretary Stimson and now Senator Elihu Root, parried

legislative thrusts by Hay, assisted apparently by Ainsworth, aimed at General

Wood and the General Staff. Hay succeeded, however, in putting through a provision

that reduced the General Staff by 20 percent, to thirty-six members. While

increasing it to fifty-five four years later in the National Defense Act of

1916 he so limited the number of officers that could be assigned to the General

Staff in Washington that only nineteen were on duty there when the United

States entered World War I. (By contrast over 1,000 were so assigned by the

end of the fighting. Yet, of these, only four had had previous General Staff

experience, and all four were general officers.) 27

-

- The National Defense Act of 1916 was the most comprehensive legislation

of its kind Congress had ever passed. It defined the roles and missions of

the Regular Army, the Na-

- [19]

- tional Guard, and the Reserves, placing the Reserve Officers' Training Corps

(ROTC) and the Plattsburg idea of summer training on a firm basis. It prescribed

in detail the organization, composition, and strength of all units in the

Army, National Guard, and Reserves.28

-

- These provisions were a compromise between the General Staff and Secretary

Garrison who favored expanding the Regular Army with Reserves under direct

federal control and traditionalists like James Hay who opposed a large standing

army and insisted upon a greater and independent role for the National Guard.

President Wilson was convinced that with Congress and the nation at large

deeply divided on the issue of preparedness such a compromise was politically

necessary. Secretary Garrison, opposed to compromise, resigned, and the President

appointed a pacifist, reform Mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, Newton D. Baker, in

his place in March 1916.29

-

- The provisions of the act affecting the General Staff and the bureaus were

largely the work of James Hay and General Ainsworth. Hay wrote later that

without Ainsworth's "vast knowledge of military law, his genius for detail,

his indefatigable industry in preparing the legislation and meeting the numerous

arguments which were argued against it," the bill could not have been

passed.30

-

- In addition to nearly forcing the General Staff out of existence Hay and

Ainsworth inserted provisions limiting its activities essentially to war planning

functions and expressly prohibiting it from interfering with the bureaus and

their administration. War College personnel, who had been acting as the military

intelligence and war planning agencies of the General Staff, were prohibited

from performing any General Staff functions. The effect was to cut back the

size of the General Staff even further. The Mobile Army Division was abolished

and its functions assigned to The Adjutant General's Office and other bureaus.

To underline these restrictions, Hay and Ainsworth inserted a further provision

decreeing that the

- [20]

- "superior" officer whose subordinate should violate them would

forfeit his pay and allowances. 31

-

- From 1916 onward the bureau chiefs regarded the National Defense Act as

their "Magna Carta." It legally guaranteed their traditional independence

of executive control by specifying the office of each chief as a statutory

agency and designating them as commanding officers of their assigned corps

or departments. No President could abolish or change these provisions without

Congressional approval. 32

-

- When war did come, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge thought "Mr. Hay by his

policy did more injury to this country at a great crisis than any one man

I have ever known of in either branch of Congress." 33

-

-

- The apparent intent of Hay, Ainsworth, and other traditionalists was to

revive through the National Defense Act the organization of the War Department

that had broken down in 1898. At least Secretary Baker thought so. As soon

as Mr. Hay was no longer chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee

and General Ainsworth had considerably less influence, Baker announced that

so far as he was concerned "The Chief of Staff, speaking in the name

of the Secretary of War, will coordinate and supervise the various bureaus

. . . of the War Department; he will advise the Secretary of War; he will

inform himself in as great detail as in his judgment seems necessary to qualify

himself adequately to advise the Secretary of War." 34

-

- After declaring war against Germany on 6 April 1917 Congress passed emergency

legislation reversing the policies of Hay

- [21]

- SECRETARY BAKER

-

- and Ainsworth by providing that the Chief of Staff should have "rank

and precedence over all other officers of the Army" and increasing the

size of the General Staff to nearly 100.35

With this authority Mr. Baker could

have asserted firm executive control over the bureaus through the Chief of

Staff in the manner of Root and Stimson. Instead for nearly a year he went

back to the traditional policy of allowing the bureaus to run themselves,

with results similar to those in the War with Spain, only far more serious.

-

- Believing he was following the confederate philosophy of Jefferson Davis,

Baker asserted that "civilian interference with commanders in the field

is dangerous." He applied the same principle in dealing with the bureau

chiefs. President Wilson also sought to run the war along traditional lines

with as little executive control as possible. Both he and Secretary Baker

exercised their authority by delegating it freely. The President left the

running of the Army and much of the industrial mobilization program to Mr.

Baker who in turn delegated his authority freely to his military commanders

and the bureau chiefs.

- [22]

- Overseas, the President and the Secretary delegated this broad authority

over military matters to General John J. Pershing and later to Maj. Gen. William

S. Graves who commanded the small expeditionary force in Siberia. In line

with their Jeffersonian philosophy of limited government both men also opposed

controls over the national economy even during war.

-

- There were serious political problems also. Both the President and Congress

ducked the issues of economic mobilization wherever and whenever possible

because of serious political disagreements throughout the country over the

role the government should play in the economy. It was a lot easier to meet

each specific issue or crisis as it came up and devise what Mr. Root had referred

to as a "jury-rigged extempore" solution. Only the near collapse

of the economy in the winter of 19171918 forced the President and Congress

to act. 36

-

- Consequently, soldiers like General Pershing regarded Baker as a great Secretary

of War because he left them alone, while business leaders like Bernard M.

Baruch were critical of him because he failed to exert effective control

over the War Department. Unlike Root and Stimson, Baker had had little contact

with the management of large-scale enterprises where the necessity for firm

executive control was taken for granted. When urged to adopt such programs,

he took refuge in procrastination because as a southern gentlemen he instinctively

avoided controversy. Without effective leadership the War Department bumped

its way from one crisis to another toward disaster.

-

- As Assistant Secretary of War Frederick P. Keppel saw it, "Baker has

learned only too well the lesson that if you leave them alone many things

will settle themselves .... Newton D. Baker succeeds in getting to first on

balls oftener than any other

- [23]

- GENERAL PERSHING

-

- man in public life. Sometimes he is called out on strikes . . . with no

evidence he has lifted the bat from his shoulders." 37

-

- The broad delegation of authority by the President and Secretary Baker to

General Pershing resurrected the position of Commanding General which had

caused so much trouble in the nineteenth century and which Mr. Root had deliberately

abolished for this reason. Mr. Baker apparently failed to appreciate Mr. Root's

purpose in replacing the Commanding General by the Chief of Staff as the Secretary's

principal military adviser. The divided authority created by the President

and Mr. Baker inevitably led to serious friction between General Pershing

and General Peyton C. March, the Chief of Staff after May 1918. March was

the first to assert vigorously his 1917 statutory "rank and precedence

over all other officers of the Army." In ignoring Mr. Root's advice Mr.

Baker was in large measure responsible for the troubles that arose.38

-

- Another issue Baker ducked repeatedly was War Depart-

- [24]

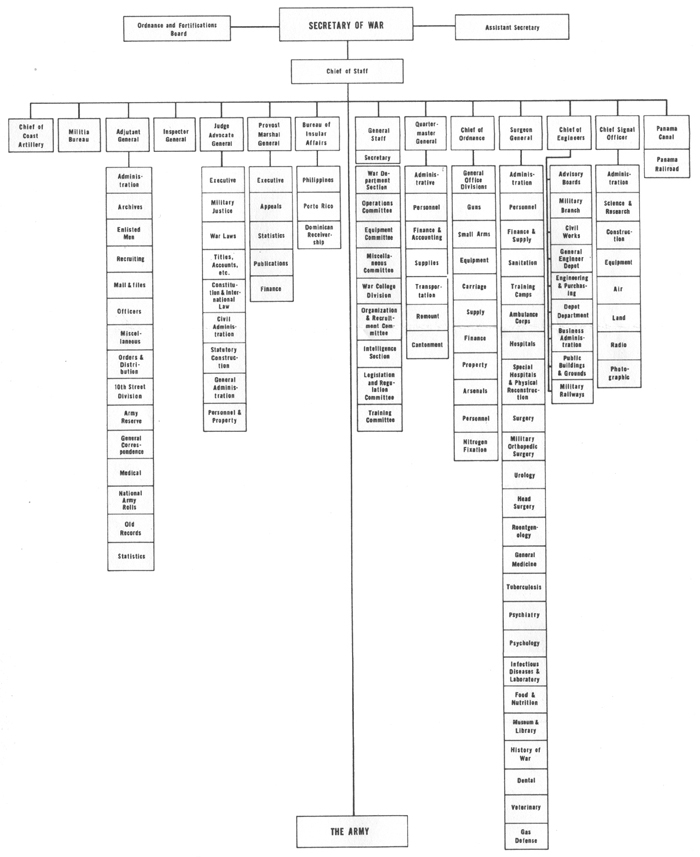

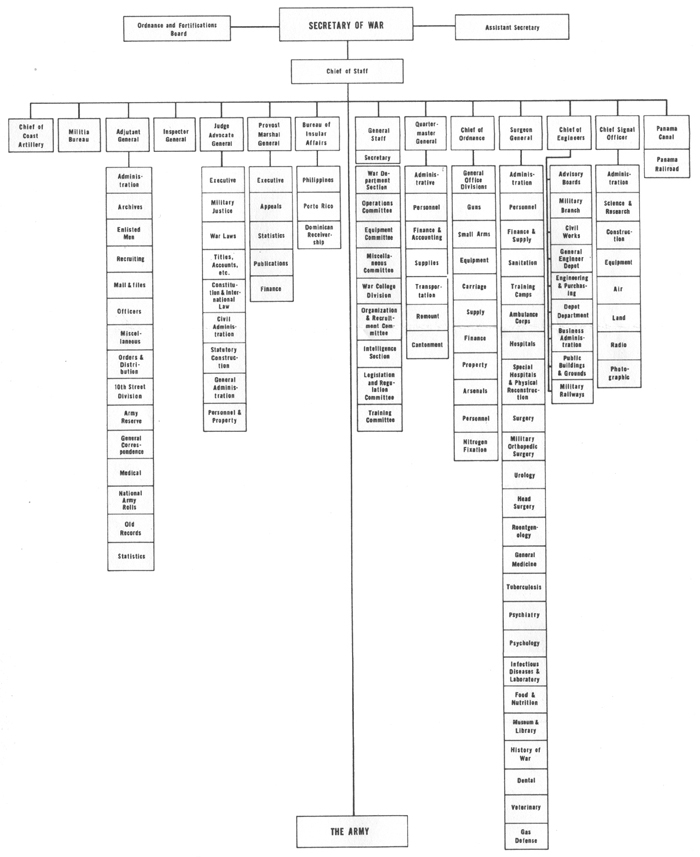

- THE WAR DEPARTMENT , LATE 1917

-

r

r

- Source: Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War

(1917-19): Zone of the Interior, pp. 16-17.

-

- Note: Provost Marshal General Appointed 22 May 1917. The Ordnance and

Fortifications Board, Ward Department, considered and recommended projects

for fortifications and examined and reported upon ordnance and other

inventions submitted to the department.

-

- ment red tape, which became as serious a problem as in 1898. Tradition and

regulations dictated that a great many trivial matters required the signature

of either the Secretary or the Chief of Staff personally, especially when

they involved accountability for funds. Maj. Gen. Tasker H. Bliss, when Assistant

Chief of Staff during the early part of the war, continually urged drastic

pruning of the department's paper work, complaining:

-

- In time of peace, it is possible that the Chief of Staff had time to give

some consideration to the question as to whether the allotment would be made

to repair a roof on a set of quarters, to repair a stable that had fallen

down, etc . . . . It is entirely impossible to do so now, and the signature

of the Chief of Staff on such papers means nothing. 39

-

- Traditionalists in the bureaus opposed any changes in the system, and Mr.

Baker sided with them. Consequently, by September 1917, the paper work in

the department was in serious disorder. Important documents were being delayed,

lost, or mislaid. Red tape again threatened to slow down the war effort, ".

. . that governmental tradition of shifting decisions about detail to higher

rank, that `passing of the buck,' which often wagged a paper along its slow

course with its tail of endorsements, was to persist through the early months

after our entry into the war." 40

Criticism

of the Secretary increased in Congress and business circles, but the President's

strong personal support and confidence enabled Baker to survive repeated crises.

41

-

- Mr. Baker administered the War Department during the first year of the war

along the lines indicated in Chart 1. Despite his own earlier interpretation

of the National Defense Act he acted during this period without an effective

Chief of Staff, dealing with the bureaus directly in the traditional manner.

He

- [25]

- treated his first two Chiefs of Staff, Maj. Gen. Hugh L. Scott and General

Bliss, as chiefs of the War Department General Staff only. Abroad much of

the time on special missions, Scott in Russia with the Root mission and Bliss

with the new Supreme War Council in Paris, they exercised little influence

in Washington. Nearing retirement, they also lacked "that certain ruthlessness

which disregards accustomed methods and individual likings in striking out

along new and untrodden paths." So did Secretary Baker.42

-

- The War Department General Staff, at that time primarily the War College

Division, during this period was not a coordinating staff but simply the department's

war planning agency, as some critics indicated it should have been all along.

Mr. Baker looked to the Chief of Staff and the General Staff for advice and

plans on raising, training, and equipping the Army. He ignored their advice

on the need for more effective control over the bureaus through the Chief

of Staff until the issue could no longer be postponed. 43

-

- There were other factors which made it difficult for the General Staff to

act effectively. Fearing Congressional reaction Baker ordered that line officers

only, and not War Department staff officers, should be promoted. General Pershing

was allowed to select any War Department officers he wanted for his own headquarters

staff. Finally experienced civil servants in the bureaus could not be commissioned

and continue to serve in their former civilian capacities. They had to be

transferred out of Washington.

-

- As a result both the General Staff and the bureaus lost experienced and

valuable personnel at a time when their services were needed most. Such key

figures as Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Kuhn, Chief of the War College Division,

and Lt. Col. John

- [26]

- McAuley Palmer left for overseas as soon as possible. From July to the end

of September the War College Division lost over a third of its staff, leaving

only twenty-four inexperienced staff officers on duty. The bureaus suffered

comparable casualties. As one critic privately wrote General Pershing, "The

policy you have adopted in your General Staff should have been adopted in

Washington. The highest type of men should have been selected and kept in

Washington on the General Staff without prejudice to their advancement. That

would have given us greater continuity of policy." 44

-

- The War College Division had become the General Staff in fact because of

the abolition by Congress of the Mobile Army Division. Retaining its prewar

organization the War College Division was divided into five functional committees

and a separate Military Intelligence Section. The committees concentrated

on raising the new Army in terms of organization and recruitment, military

operations, equipment, and training. The fifth committee dealing with legislation

and regulations, prepared the necessary administrative and legal support.

-

- The Military Operations Committee was responsible for operational planning,

including the defense of the United States and its overseas possessions. It

drew up the plans for sending troops to Europe, prepared studies on the amount

of shipping available, and issued troop movement schedules. The Equipment

Committee was responsible for supplying troops, preparing standard tables

of equipment for each unit, distributing supplies among the troops, procurement

planning, and maintaining liaison with the supply bureaus. It had no authority

over the bureaus. It could merely request action from them.

-

- A serious drawback was the General Staff's awkward loca-

- [27]

- tion across town in the War College which inevitably created delay and ungenerous

remarks that it had become a dead-letter office. Consequently, both the Military

Operations and Equipment Committees moved from the War College to the main

War Department building in the fall of 1917 to perform their functions more

effectively and expeditiously. At that time they became known collectively

as the War Department Section of the War Department General Staff. 45

-

- The territorial departments of the Army were reorganized and increased from

four to six after the declaration of war to assist the War Department in the

administration of the Army and to mobilize the National Guard and Reserve

forces. The departments were the Northeastern, Eastern, Southeastern, Central,

Southern, and Western. The Southern Department was responsible for coping

with the continued depredations of warring Mexican factions along the border,

tying down between 30,000 to 130,000 men at various times in over 255 small

posts. It was a major operation and supplying these men was an added strain

on the already overburdened war economy. Overseas there were the Hawaiian

and Philippine Departments to which a new Panama Canal Department was added

in July 1917. The Philippine Department included a small detachment of 1,500

men stationed in China with headquarters at Tientsin. It was also responsible

for assembling the 2,700 men assigned to General Graves' Siberian expedition

in the summer of 1918. These departments all reported to the War Department.

General Pershing reported directly to Secretary Baker also, not through the

Chief of Staff. 46

-

- The General Staff planned, scheduled, and co-ordinated its programs for

mobilizing, training, and transporting the Army overseas. So far as the supply

bureaus were concerned there was little planning and no co-ordination. At

the outbreak of war,

- [28]

- Secretary Baker simply issued "hunting licenses" to the bureaus

and turned them loose on an unprepared economy. Baker and other responsible

officials should have anticipated the chaos that inevitably followed. By July

more than 150 War Department purchasing committees were competing with each

other for scarce supplies in the open market.

-

- Anticipating shortages, agencies and their personnel aggressively sought

to corner the markets for critical items. The Adjutant General rubbed Mr.

Baker's nose into the problem personally one day by boasting that he had cornered

the American market for typewriters. "There is going to be the greatest

competition for typewriters around here, and I have them all." 47

-

- Similarly the commander of the Rock Island Arsenal cornered the market for

leather. "Well, that was wrong, you know," he later told Congress,

"but I went on the proposition that it was up to me to look after my

particular job, and I proceeded to do so." 48

-

- Simply expressed this maxim has been part of the traditional American dogma

of individualism. It applies to large organizations and small, government

and private. It worked satisfactorily in a thinly populated, expanding rural

America, but as many responsible industrialists had foreseen earlier competition

could mean disaster during war in a mass urban industrial society. 49

-

- As one severe critic bluntly put it, "The supply situation was as nearly

a perfect mess as can be imagined . . . . It seemed a hopeless tangle."

50

Among the bureaus were five, later

nine, separate, independent systems for estimating requirements with no inventory

controls to determine the

- [29]

- amount of supplies available in various depots. Some depots had more space

to store supplies than they needed, while others did not have enough. There

were five different sources of supply and property accountability, always

a source of time-consuming red tape, five different accounting systems, and

as many incompatible statistical and reporting systems which were of use only

to the bureau or depot concerned. For example, the War Department, according

to Bernard Baruch, could not find out from the bureaus how much toluol, a

basic ingredient of TNT, it needed.

-

- There were no agencies anywhere in the department, or even within some bureaus,

for determining industrial and transportation priorities similar to those

the General Staff prepared for troop movement schedules. Competition among

the bureaus for transportation caused bottlenecks that, by December 1917,

imperiled the fuel supplies of war industries. Finally, the bureaus dealt

directly with the War Industries Board, other civilian war agencies, and with

Allied purchasing missions, but there was no one to represent the department

as a whole. As Maj. Gen. George W. Burr, Director of Purchase, Storage, and

Traffic, after the war told Congress, "The Bureau System did not work

in an emergency, and it never will work." 51

-

- Despite the growing evidence of impending Industrial disaster Mr. Baker

persisted throughout the fall of 1917 in opposing controls over industry,

transportation, and over the bureaus. Ultimately in December a mammoth congestion

of rail and ocean traffic developed in the New York area and the northeast

generally. A particularly severe winter, which froze rail-switches and even

coal piled out in the open, and the menace to Atlantic shipping of German

submarines made matters worse.

-

- For lack of effective controls a vast amount of freight clogged yards in

Atlantic ports and eastern industrial areas with

- [30]

- literally thousands of rail cars, which could not be unloaded for lack of

space and labor or even located for lack of identification. A similar rail

tie-up in New York had occurred just a year before.

-

- The terminals in Philadelphia, for example, were filled with carloads of

lumber from Washington and Oregon destined for the Navy's Hog Island site

long before there were any rail facilities there for unloading the cars. In

the end ships built with these materials were not completed until the war

was over. 52

-

- For lack of adequate warehousing, wharves and docks were used, even ships,

which were badly needed for transporting troops and supplies. Freight cars

of coal, frozen or not, could not get through or were lost in the congestion,

threatening paralysis of war industry and holding up bunkering of ships. By

December more than 45,000 carloads were backed up as far as Pittsburgh and

Buffalo. 53

-

-

- The crisis in December 1917 came at a time when Allied fortunes in Europe

were at their lowest ebb. The British campaign in Flanders had bogged down

ingloriously in mud. The Italian Army had suffered a disastrous defeat at

Caporetto, the French Army was still recovering from the effects of the mutinies

six months earlier, and the new Bolshevik regime in Russia was discussing

peace terms with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk.

-

- Industrialists, particularly those associated with the War Industries Board

(WIB) , continually warned President Wilson and others of impending disaster

if firm controls over the economy were not established. Thomas N. Perkins,

a Boston corporation lawyer serving with the WIB, in December wrote a memorandum

calling for a civilian supply department, such

- [31]

- as Britain had created, which would take over such functions from the War

Department and other agencies. 54

-

- The paralysis of rail and ocean traffic in New York, the threat of war industry

in the East shutting down for lack of coal, and similar evidence in December

prompted Senator George E. Chamberlain, chairman of the Senate Military Affairs

Committee, to investigate the problem. His hearings uncovered evidence of

much waste and inefficiency among the War Department bureaus, and he concluded,

like Mr. Perkins of the War Industries Board, that a separate civilian supply

department should be created on the British model. Senator James W. Wadsworth

of New York summed up the attitude of his colleagues on the committee and

of industrialists generally by asserting that "the bureaus' hide-bound

traditions were fouled up in red-tape." Procurement and supply was not,

he said, properly a military function at all and could not be performed adequately

by military men. It was a job for businessmen. 55

-

- These events, particularly the Perkins recommendation for a separate supply

department, finally prodded Baker into attempting to centralize control over

the department's disparate and fragmented supply operations. The process had

actually begun in the summer of 1917 when responsibility for construction

and for ports of embarkation had been transferred from the Quartermaster Corps

to two new agencies under the direct supervision of the War College Division.56

In November he replaced Assistant Secretary of War William M. Ingraham, a

nonentity appointed in May 1916 along with Baker, with Benedict Crowell, a

Cleveland industrialist with a Reserve Quartermaster commission and an exponent

of firm executive control over the bureaus.57

-

- Responding to pressure from Congress, the War Industries Board, and events

.themselves, Baker accepted a War College

- [32]

- proposal in December for centralizing the department's supply system along

functional lines in the General Staff. His first act was to recall from retirement

Maj. Gen. George W. Goethals of Panama Canal fame, making him Acting Quartermaster

General on 20 December and a week later on 28 December also appointing him

"director" of a new General Staff agency, the Storage and Traffic

Division. The intent in creating this agency was to establish control over

such functions among the bureaus along with the Embarkation Service which

was placed under its direct supervision. Next on 11 January 1918 a separate

Purchasing Service was created to co-ordinate these activities in the War

Department.58

-

- Mr. Crowell, Goethals' immediate superior, said, "When a nation is

committed to a struggle for existence, only a man impatient of hampering actions

is likely to carry a great project through to success." General Goethals

was such a man, he thought, and his "lack of previous intimate contact

with the red tape and machinery" of the bureaus plus his judgment and

a determination to succeed made him a good executive. He readily accepted

responsibility and did not drive his superiors "to distraction by continual

requests for authority to act." 59

-

- When Goethals first took charge of the Quartermaster Corps he thought the

only way to control the disruptive, wasteful competition among the bureaus

was to create a civilian supply department as Mr. Perkins of the WIB and Senator

Chamberlain's committee recommended. Since President Wilson and Secretary

Baker opposed this idea, Goethals determined to consolidate and integrate

War Department purchases internally to eliminate competition.

-

- General Goethals also shared the views of industrialists and the War Industries

Board that the Quartermaster Corps was essentially a huge purchasing organization

and not a military operation. Consequently he proceeded to staff it with civilians

who he thought knew more about purchasing than military men. One of his first

appointments was Harry M. Adams, vice

- [33]

- GENERAL GOETHALS

-

- president in charge of traffic for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, whom he

made Director of Inland Traffic, later called the Inland Traffic Service,

on 11 January 1918. At about the same time Mr. Baker appointed Edward R. Stettinius,

a partner in J. P. Morgan and Company. Surveyor of Supplies to work under

Goethals.

-

- Goethals most valuable civilian assistant was Robert J. Thorne, president

of Montgomery Ward, who came to work on 1 January 1918 as a volunteer civilian

aide to Goethals. On 8 March Goethals assigned him as Assistant to the Acting

Quartermaster General. Instructions and directives from Mr. Thorne in performing

his duties under General Goethals "will have the force and effect as

if performed by the Acting Quartermaster General

himself." 60

-

- It would be difficult to overestimate the contribution made by representatives

of industry and business, including those

- [34]

- apostles of Frederick W. Taylor, the efficiency experts, in attempting to

rationalize the Army's supply system. They infiltrated the department's supply

organization at all levels of command, some in uniform, some not, some volunteer

civilian advisers, others appointed officially. The War Industries Board,

for example, loaned Mr. Baker's nemesis, Thomas N. Perkins, in April to Mr.

Crowell who appointed him a member of a Committee of Three to plan a reorganization

of the Army's supply system along rational businesslike lines.61

-

- There were other military officers like General Goethals who believed the

Army's supply system needed drastic reorganization. Brig. Gen. Robert E. Wood,

an Engineer officer who had served as General Goethals' "good right arm"

in building the Panama Canal, was one.62

At Goethals' request he was recalled

from France and on 10 May made Acting Quartermaster General under General

Goethals who had just become Director of Purchase, Storage, and Traffic. Wood

left the Army on 1 March 1919 to join Mr. Thorne at Montgomery Ward as vice

president and general merchandise manager.63

-

- Another was Col. Hugh S. Johnson. As Deputy Provost Marshal General he had

been responsible for planning and executing the Selective Service Act. In

March 1918 Assistant Secretary Crowell appointed him chairman of the Committee

of Three to devise a plan for reorganizing the Army's supply system. Promoted

to brigadier general on 15 April, Johnson became Director of Purchase and

Supplies under General Goethals with Gerard Swope, vice president of Western

Electric, as his assistant director. Johnson, brilliant, young, inpatient,

and abrasive, was determined to consolidate and integrate the Army's supply

system despite the opposition of

- [35]

- the bureau chiefs who, he said, jealously guarded their "protocol,

prerogatives, and functions." 64

-

- He was soon in hot water with many of his military colleagues, including

the Chief of Staff. Disgruntled, he left for a field command in October and

left the Army after the war to become an official of the Moline Plow Company.

During the New Deal he gained notoriety as head of the National Recovery

Administration.65

-

- Secretary Baker in the meantime reorganized his own office and staff. In

April Congress authorized a Second and Third Assistant Secretary of War. The

Second Assistant at first was Edward R. Stettinius who was responsible for

purchases and supplies under Mr. Crowell. The Third Assistant Secretary was

Frederick P. Keppel, on leave as dean of Columbia University, who had been

a general troubleshooter in Mr. Baker's office for some time. Now he became

responsible for civilian relations and nonmilitary aspects of Army life, including

relations with the Red Cross, YMCA, and Army chaplains.66

-

- Mr. Stettinius went overseas in July 1918 and in August became the American

representative on the Inter-Allied Munitions Council. His successor as Second

Assistant Secretary was John D. Ryan, a mining engineer whom President Wilson

had appointed Director of Aircraft Production in April. He now became Assistant

Secretary of War and Director of the Air Service. 67

-

- Mr. Crowell at the same time was given additional duties as Director of

Munitions. General Goethals reported both to him and to the Chief of Staff

in his various capacities.

-

- Much earlier, in October 1917, Mr. Baker had appointed Emmett Jay Scott,

secretary of Tuskegee Institute, as Special

- [36]

- Assistant to the Secretary of War on matters affecting black soldiers.68

-

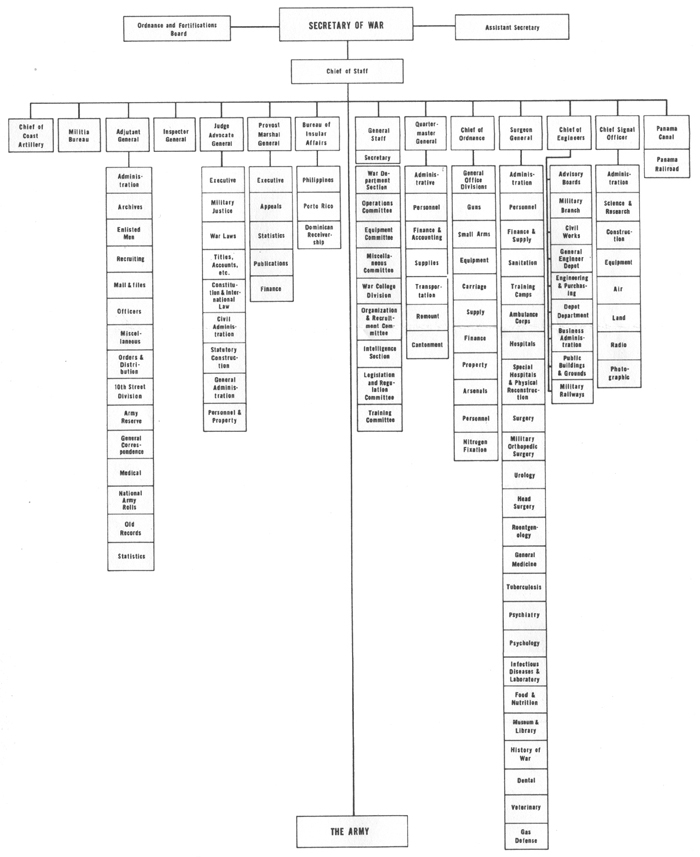

- The first wholesale reorganization of the General Staff itself took place

on 9 February 1918. Instead of being an operational planning staff based on

the old War College Division it was now to be, at least on paper, a directing

staff responsible for supervising all War Department activities not falling

under Mr. Crowell. The Chief of Staff was specifically directed to supervise

and co-ordinate "the several corps, bureaus and all other agencies of

the Military Establishment . . . to the end that the policies of the Secretary

of War may be harmoniously executed." 69

-

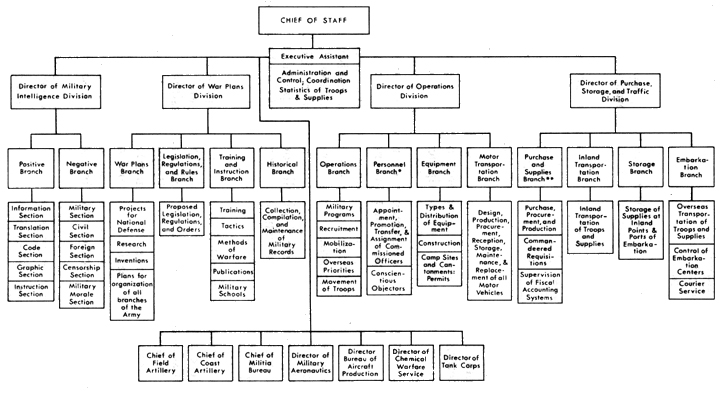

- The General Staff, as reorganized along functional lines, consisted of the

Chief of Staff and five Assistant Chiefs of Staff: one, an Executive Assistant

responsible for administration, control, and intelligence; the president of

the War College as head of a War Planning Division which absorbed the functions

of the old War College Division; a Director of Operations who took over the

functions of the Operations and Equipment Committees; the new Director of

Storage and Traffic; and the Director of Purchases and Supplies, Brig. Gen.

Palmer E. Pierce. The latter reported to Crowell and also served as liaison

with the War Industries Board.

-

- The War Industries Board created in the summer of 1917 was responsible on

paper for economic mobilization, but it lacked the authority to make its decisions

stick. Its first two chairmen, Frank Scott and Daniel Willard, quit, Scott

in October 1917 because his health had broken down under the frustration of

accomplishing nothing, while Willard, president of the Baltimore and Ohio

Railroad, left on I1 January 1918 in disgust, during the administration's

crisis with the Chamberlain Committee. 70

-

- Finally President Wilson, despite the continued opposition of Secretary

Baker, on 4 March 1918 appointed Bernard Baruch chairman of the War Industries

Board with effective executive control over the nation's war industry and

agencies of the government, including the War Department. Instead of nego-

- [37]

- GENERAL MARCH

-

- tiating directly with industries the services would now have to submit their

requirements for items in short supply with detailed justifications to the

WIB. The War Industries Board would then determine allocation of scarce commodities

and transportation priorities. This forced a major reorganization of the War

Industries Board itself based on centralized authority and decentralized operations,

which in turn required a parallel reorganization of the War Department's supply

system under General Goethals.71

-

- Baker's appointments of Benedict Crowell and General Goethals were made

with the aim of establishing control over the War Department's supply system.

Important as these choices were even more important was Mr. Baker's appointment

of Maj. Gen. Peyton C. March, whom he recalled from France to replace General

Tasker H. Bliss as Chief of Staff, who now became the American representative

on the Supreme War Council in Paris. General March became Acting Chief of

Staff on the same day, 4 March, that Mr. Baruch obtained the authority he

needed to make the War Industries Board effective.

- [38]

- March's official designation as Chief of Staff with the rank of general came

on 20 May 1918.72

-

- March, who believed the shortest distance between two points was a straight

line, was a hard-working ruthless executive. He made a lot of enemies in the

process, especially in Congress.73

-

- March had one supreme goal, to establish effective executive control over

the War Department's operations under the Chief of Staff subject to the Secretary's

direction. He accepted General Goethals' special relations with Mr. Crowell,

and, in fact, the two got along very well because in the area of supply they

both agreed. For example, both Goethals and March agreed that General Pierce

was not very effective as Director of Purchases and Supplies. March abruptly

fired Pierce and replaced him with Colonel Johnson who was promoted by the

President to brigadier general.

-

- When Mr. Baker returned from France in mid-April he found General March

had already instituted a thorough house cleaning in the department, eliminating

red tape and getting rid of deadwood. From that moment on Baker supported

March loyally in his efforts to establish effective unity of command over

the department just as strongly as he had earlier opposed such controls. It

meant abandoning his previous traditionalist approach of working through the

bureau chiefs for the Root Stimson policy of allying himself with the Chief

of Staff.

-

- One of March's first projects was to prune back the red tape which had snarled

the department's operations. The center of this program was the new Office

of the Executive Assistant to the Chief of Staff. At first this was Maj. Gen.

William S. Graves, who was assigned in July to command the American expeditionary

force in Siberia. Maj. Gen. Frank McIntyre, then Chief, Bureau of Insular

Affairs, replaced him until January 1919. Graves had been Secretary of the

General Staff, and in that capacity Col. Percy P. Bishop replaced him until

he went overseas in September and was then replaced by Col. Fulton Q. C. Gardner.

75

Both the Executive Assistant and the Secretary of

- [39]

- the General Staff worked to improve the business methods of the General

Staff. The Executive Division became a control division for co-ordinating

departmental operations. A Cable Section was responsible for routing and ensuring

prompt action on all communications to and from the General Staff as well

as coding and decoding them. A new Statistics Branch, transferred from the

War Industries Board, prepared a detailed weekly report on the progress of

the war and economic mobilization for the Chief of Staff, the Secretary, and

the President. As a result the Secretary and Chief of Staff could make decisions

based on relatively accurate data instead of guesswork. Armed with these statistics

the department could also present more effectively its requirements to the

War Industries Board.

-

- A Coordination Branch was responsible for studying and supervising "the

organization, administration, and methods of all the divisions of the General

Staff and the several bureaus, corps or other agencies of the War Department,

to the end that the activities of all such agencies may be coordinated, duplication

of work avoided, harmonious action secured, and unnecessary machinery of organization

may be eliminated. 76

-

- General March replaced Maj. Gen. Henry P. McCain, an adherent of the Ainsworth

school, as Adjutant General with Maj. Gen. Peter C. Harris, an infantry officer

rather than a deskman. Harris continued the efforts begun under Stimson and

Wood to simplify the department's paper work. He reduced the number of separate

records kept on enlisted men by company commanders from nine to two, eliminating

the celebrated, but cumbersome, muster roll. The War Department and the Army

could no longer afford the luxury of such documents whose cost in time and

manpower far exceeded their usefulness.77

- [40]

- The change from decentralized operations through the bureaus to centralized

control along functional lines followed a path strewn with many obstacles.

One major obstacle was that the bureaus were still solidly entrenched in power

by Section 5 of the National Security Act of 1916 which Ainsworth and Hay

had deliberately inserted to hamstring the General Staff. For the same reason

the new authority of the War Industries Board rested on dubious legal grounds.

The WIB succeeded primarily because the attitude in Congress, thanks to the

Chamberlain Committee, had changed toward the bureaus whose destructive competition,

red tape, and delay seriously threatened the war effort. Only the enactment

on 20 May 1918 of the Overman Act, granting the President authority to reorganize

government agencies in the interest of greater efficiency for the duration

of the war, gave the WIB legal authority over industrial mobilization and

the General Staff authority necessary to reorganize the Army's fragmented

supply system.78

-

- In practice the changes in organization toward a centralized supply system

were a gradual process of trial and error made without interrupting the production

and supply of material needed at the front; it was "like constructing

Grand Central Station without disrupting train schedules." 79

-

- Continuing their opposition the bureaus fought consolidation and change

every step of the way. As General Johnson saw it, "We did by rough assault"

consolidate purchase activities but not "without agonized writhings and

enmities, some of which have never entirely disappeared." 80

-

- Until the Overman Act's passage, the reorganization of the General Staff

under General Order 14 had been really only a paper reorganization. The Directorates

of Storage and Traffic and of Purchase were little more than holding companies

with operations still fragmented among the still-independent, competing bureaus.

-

- When Mr. Baruch reorganized the War Industries Board, a parallel reorganization

of the War Department's supply system followed. Stettinius,

Crowell, Goethals, and March

- [41]

- agreed to appoint Johnson chairman of the Committee of Three on 2 April

to examine the problems of the Army's supply system and propose a solution.

Johnson's colleagues were Thomas N. Perkins of the WIB and Charles R. Day,

a well-known Philadelphia engineer and efficiency expert. 81

-

- The Committee of Three, as it was known, noting the inefficiency of the

existing bureau system, asserted in its report that any reorganization must

unify and integrate the several bureaus on functional lines. At the top its

organization should parallel that of the recently reorganized WIB to provide

single War Department representatives instead of five in the areas of commodities,

priorities, clearances, and requirements as well as purchase, production,

finance, standardization of control, and replacement of Allied war supplies.

It should transmit the military supply requirements from the Operations Division

of the General Staff to the supply bureaus as the basis of their own requirements.82

-

- Unification of the Army's supply system meant effective centralized control

over the bureaus. The committee's report went through several revisions, but

they all insisted that the fundamental issue of controlling the bureaus demanded

standardizing their statistics. "There will never be effective action

by the Office of Purchase and Storage until it has developed statistical control

over the bureaus . . . . The whole organizational pattern is clipped out of

statistics." 83

-

- Bureau statistics, the committee insisted, should be uniform to provide

the Director of Purchases with reports on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis.

He must also have complete access to bureau statistics for purposes of auditing

them. Without such direct control it would be better to forget the whole thing.

"The office is built upon a foundation of statistics or it had far better

not exist." 84

- [42]

- The obstacles to gaining control over bureaus' statistics were enormous.

At the bottom were the bureaus whose statistics were often inadequate and

unreliable. For instance, The Quartermaster General's Office lacked information

on the inventory in its depots across the country. Each depot had its own

statistics which were unrelated to those of other depots. 85

The bureaus fought

bitterly all the way against changing their traditional methods.86

-

- Second, under the reorganization of the General Staff of 9 February the

Statistical Branch established in the Executive Division of the General Staff

was clearly assigned responsibility for collecting, compiling, and analyzing

statistics "from all the areas of the Military Establishment." Headed

by Dr. Leonard P. Ayres of the Russell Sage Foundation, it had been transferred

from the War Industries Board because the War Department simply had no central

statistical organization of its own. 87

-

- While the Central Statistical Branch could compile and collect, it could

not standardize the bureaus' statistics. For this reason the Committee of

Three insisted that the Division of Purchase and Supply should be responsible

for this function.

-

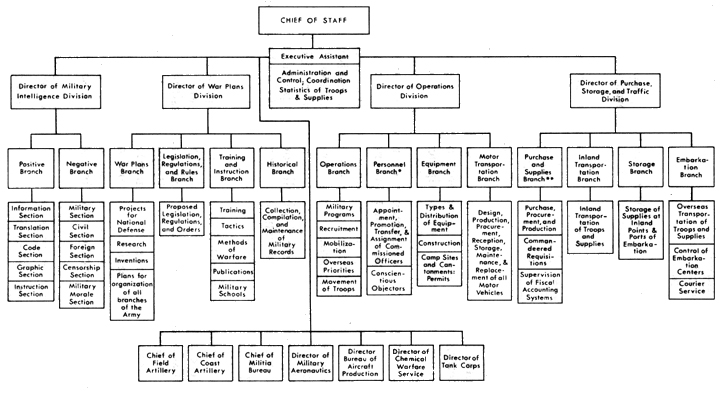

- March's response to the report of the Committee of Three was a general order

of 16 April which consolidated the Purchase and Supply and the Storage and

Traffic Divisions into one Directorate of Purchase, Storage, and Traffic (PS&T)

under Goethals who still continued to function as Acting Quartermaster General.

The order also abolished the Office of Surveyor General of Supplies held by

Mr. Stettinius, who then became, as mentioned above, Second Assistant Secretary

of War for Purchase and Supplies. In May General Wood returned to become Acting

Quartermaster General, while General Johnson had dual responsibilities as

War Department representative on the WIB Priorities Board and as Director

of Purchase and Supply. Gerard Swope, vice president of Western Electric,

became assistant director. 88

- [43]

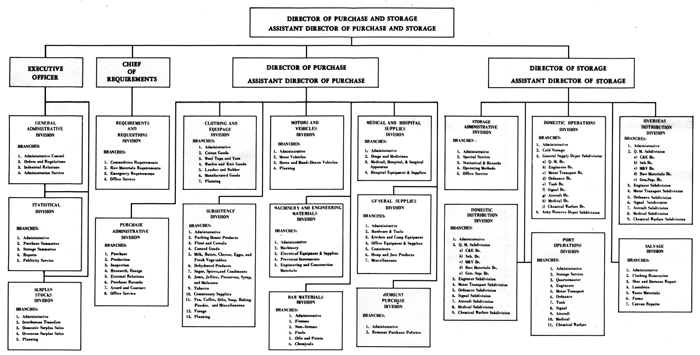

- When the Overman Act became law, functionalizing the Army's supply bureaus

began in earnest on the principle urged by industrialists of centralized control.

and decentralized operations. The argument over statistical control continued.

Col. Rodney Hitt, Chief of the Statistics and Requirements Branch, PS&T,

wrote after the war that there was "an animated and protracted discussion

on this whole subject of a statistical organization for the Purchase and Supply

Division, with the final result that the Chief of Staff did not approve the

proposition of transferring control over the Statistical Branch of the General

Staff to the Purchase and Supply Division." 89

This seems to have been

the basis for the growing mutual disenchantment between March and Johnson

which led to the latter's departure from the General Staff in October for

a field command.90

-

- The Statistical Branch did try to help the Division of Purchase and Supplies

by lending them personnel, but the bureaus dragged their feet and would not

provide qualified personnel from their agencies. Only in September did General

March grant authority to create a Requirements Branch in the Office of the

Director of Purchase, Storage, and Traffic responsible for co-ordinating calculations

of requirements among the bureaus. Obtaining qualified personnel continued

to hamper operations, and only a beginning was made in setting up control

over the bureaus' statistics when the war ended. About all that was accomplished

was the establishment of a uniform system for calculating requirements.91

-

- Statistics aside, the Overman Act led Goethals, Thorne, Johnson, and Swope

to argue that the bureaus should now be consolidated into a single service

of supply. Goethals in a memorandum of 18 July to General March forcefully

recapitulated the shortcomings of the existing system of separate bureaus.

Despite recent changes the present system did not provide for effective executive

control over their operations. What was required was consolidation along functional

lines under the Director of Purchase, Storage, and Traffic "whose functions

shall be executive-not supervisory," and "in command of the supply

organization," except for procurement,

- [44]

- production, and supply of artillery, aircraft, and other items of a highly

technical nature. To avoid interfering with current operations, the whole

reorganization should take place gradually. 92

-

- General March approved the Goethals' proposals a month later on 26 August

as part of a larger reorganization of the General Staff. (Chart 2)

-