(Editor's note: This story uses the term black as opposed to African-American. America itself was only beginning to emerge as an identity during the Revolution. Most people thought of themselves as Virginians or New Yorkers or citizens of any of the other 11 colonies. No one would have used the term African-American, and as Revolutionary-era names for black Americans would be considered offensive today, Soldiers has settled on black as a compromise.)

FORT MEADE, Md. (Feb. 27, 2013) -- It's the winter of 1777-1778. Under Gen. George Washington, the Continental Army is waiting out the winter at Valley Forge, Penn. Just one year earlier, they had led lighting-fast, surprise attacks against the British at Trenton and Princeton, N.J. But now, many of the Soldiers are without shoes and blankets. They're starving. They're suffering from exposure, typhus, dysentery and pneumonia. They're dying and they're deserting and Washington has no way to replace them. States aren't meeting their militia quotas. There simply aren't enough willing and able men to left to fight -- willing and able white men, that is.

At the start of the war, Washington had been a vocal opponent of recruiting black men, both free and especially slaves. He wasn't alone: Most southern slave owners (and many northern slave owners), found the idea of training and arming slaves and thereby abetting a possible slave rebellion far more terrifying than the British. Black men had long served in colonial militias and probably even saw action during the French and Indian War, explained retired Maj. Glenn Williams, a historian at the U.S. Army Center for Military History, but they had usually been relegated to support roles like digging ditches. In fact, he continued, most southern militias had been created precisely to fight off slave insurrections.

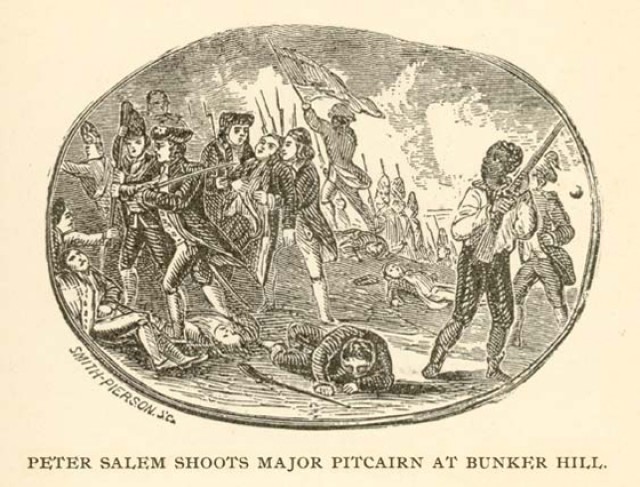

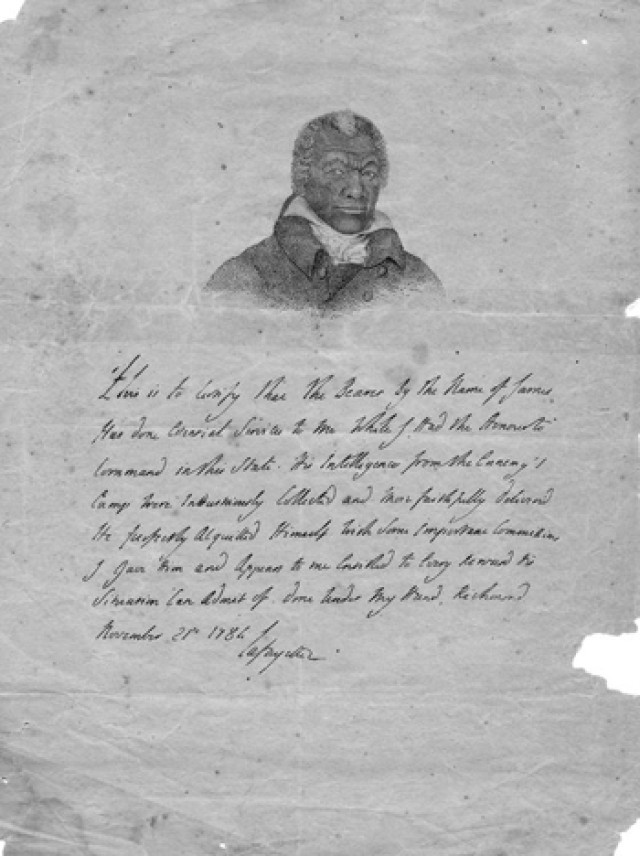

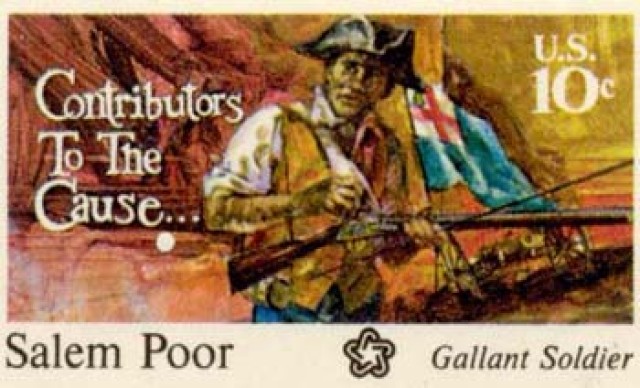

As war with Britain broke out in the spring of 1775, however, Massachusetts patriots needed every man they could get, and a number of black men -- both slave and free -- served bravely at Lexington and Concord and then at the Battle of Bunker Hill. In fact, according to documents archived on www.fold3.com, a former slave named Salem Poor performed so heroically at Bunker Hill -- exactly what he did has been lost to history -- that 14 officers wrote to the Massachusetts legislature, commending him as a "brave and gallant Soldier" who deserved a reward. Valor like this wasn't enough, however, and shortly after his appointment as commander in chief, Washington signed an order forbidding the recruitment of all blacks.

The British saw an opportunity to divide the colonies, however, and the royal governor of Virginia offered freedom to any slave who ran away to join British forces. Thousands took him up on it, and Washington relented almost immediately. In fact, the famous picture of him crossing the Delaware on Christmas Day, 1776, also features a black Soldier who many historians, according to "Come all you Brave Soldiers" by Clinton Cox, believe is Prince Whipple, one of Washington's own bodyguards, who had been kidnapped into slavery as a child and was serving in exchange for freedom. Another black Soldier, Primus Hall, reportedly tracked down and single-handedly captured several British soldiers after the battle of Princeton a week later.

These were freemen, however, freemen and slaves who were serving in place of their masters, fighting for freedom they would never see for themselves. (In many cases, their enlistment bonuses or even their pay went straight to their masters.) Washington still wasn't prepared to go as far as recruiting and freeing slaves, but many northerners had begun to question how they could call for freedom and enslave others. As that terrible winter at Valley Forge dragged on, the state of Rhode Island learned it needed to raise more troops than it could supply. State legislators not only promised to free all black, Indian and mulatto slaves who enlisted in the new 1st Rhode Island Regiment, but offered to compensate their owners. Desperate for manpower, Washington reluctantly agreed, and more than 140 black men signed up for what was better known as the "Black Regiment," according to Williams, and served until Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Va., in 1781.

In fact, they fought so bravely and inflicted so many casualties on Hessian mercenaries during the battle of Newport, R.I., in the summer of 1778, that Williams said one Hessian officer resigned his commission rather than lead his men against the 1st Rhode Island after the unit had repelled three fierce Hessian assaults. He didn't want his men to think he was leading them to slaughter.

The 1st Rhode Island was a segregated unit, with white officers and separate companies designated for black and white Soldiers. It was the Continental Army's only segregated unit, though. In the rest of the Army, the few blacks who served with each company were fully integrated: They fought, drilled, marched, ate and slept alongside their white counterparts. There was never enough food or clothes or even pay for anyone, but they shared these hardships equally.

After watching a review of the Continental Army in New York, one French officer estimated that as much as a quarter of the Army was black. He may have been looking at the 1st Rhode Island or units from Connecticut and New Jersey, which also had high rates of black enlistment, Williams explained. Many muster roles have been destroyed so there isn't an exact count, but Williams said most historians believe that 10 to 15 percent is a more accurate representation of black Soldiers who served in the Revolution. They served in almost every unit, in every battle from Concord to Fort Ticonderoga to Trenton to Yorktown.

"I've heard one analysis say that the Army during the Revolutionary War was the most integrated that the Army would be until the Korean War," Williams said. "World War

I and World War II both, and of course in the Civil War, there were lots of blacks in uniform, but the men were segregated into separate units. Even the Rhode Island regiment was half black, half white, and the men were segregated into their own companies, but in the rest of the Army, they were integrated throughout the regiments."

It was a war for freedom, not only for their country, but for themselves. After the men of the1st Rhode Island and other black Soldiers served bravely at Yorktown alongside southern militiamen whose jobs it had been to round up runaway slaves, the war gradually drew to a close. Soldiers began to trickle home. Some black Soldiers like those in the 1st Rhode Island, went on to new lives as freemen. Far too many, however, returned to the yoke of slavery, some for a few years until their masters remembered promising to free them if they served, but others, having fought for freedom, were doomed to remain slaves forever.

And then they were forgotten. The new Congress passed laws forbidding blacks to serve in the military, and by the time it offered pensions to the veterans of the Revolutionary War, Williams said that most of the black heroes were already dead.

He calls their service and their heroism "invaluable." It "came at a time when the new United States needed it very badly and they stepped up and they took their place in the ranks. If they were misrepresented in our histories before, then we owe it to them to make sure we include it now, because they certainly did their part to earn not only their own freedom, but ours as well. We should never forget that for them, it was a double fight for liberty: their own and their country's."

Social Sharing