FORT LEE, Va. (Feb. 7, 2013) -- Like all histories, that of the Black American is storied, complicated and filled with triumph and tragedy. The following vignettes are reflections on the diversity of the past and how Black Americans have impacted the present.

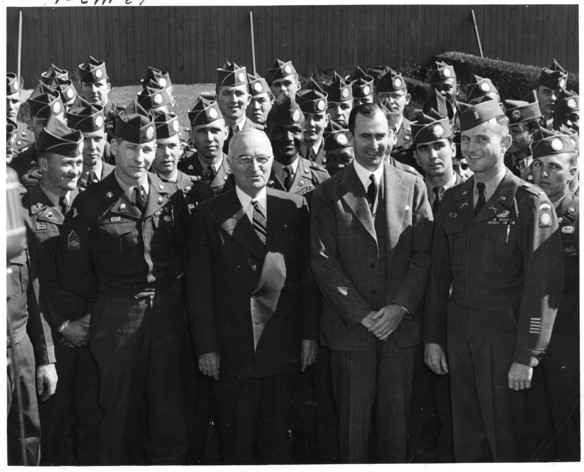

1. The intent of President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981was to end segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces, not only on the grounds that it was inefficient but it was the right thing to do. EO 9981, however, didn't solve issues related to race but rather laid a foundation for better race relations and subsequently a more effective fighting force.

It must be pointed out that Truman took an enormous risk in signing the order. A proclaimed son of Confederates, Truman was also a progressive who was moved by reports of violence committed against black veterans who fought for their country during World War II. He knew it was the right decision and stood by it, just as he did when he ousted the popular war hero Gen. Douglas McArthur. It was with the same sense of audacity that he issued the order on July 26, 1948. The ground breaking policy caused an uproar among the ranks. The president, however, was undaunted yet patient and understanding. He realized that such a policy couldn't immediately change attitudes and had enough forethought to make accommodations for an orderly, reasonable transition. He was insistent as well. When the Secretary of the Army failed to follow his directives a year after the order was signed, he was forced to retire. It was not until 1953, the final year of Truman's administration, that the armed forces seemed well on its way to integration. The last all-black units were gone by 1954, roughly six years after EO 9981 was signed.

2. Jackie Robinson was not the first African-American to break the color barrier in major league baseball. It is fact if it's applied to the modern era. The absolute distinction belongs to Moses Fleetwood Walker. In 1884, the Ohio native played catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association, a major league at that time that often competed with the National League for baseball dominance.

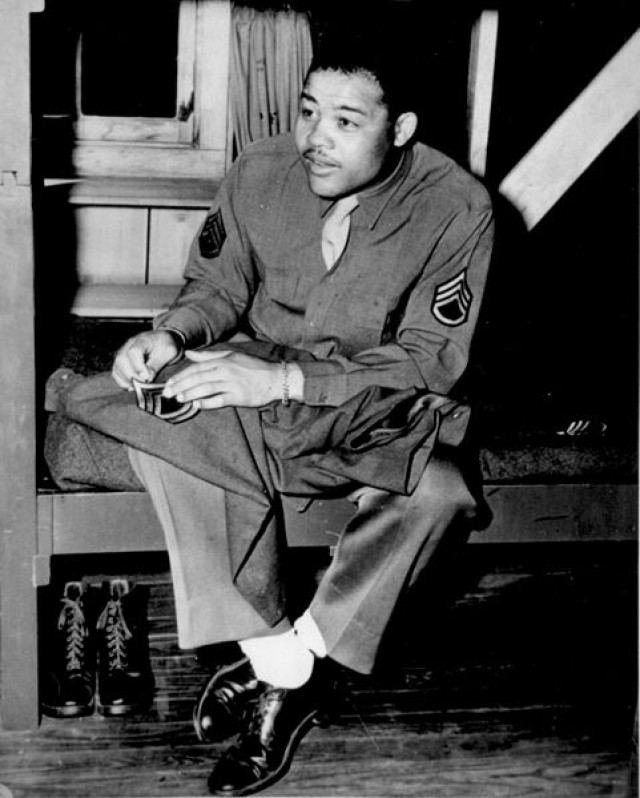

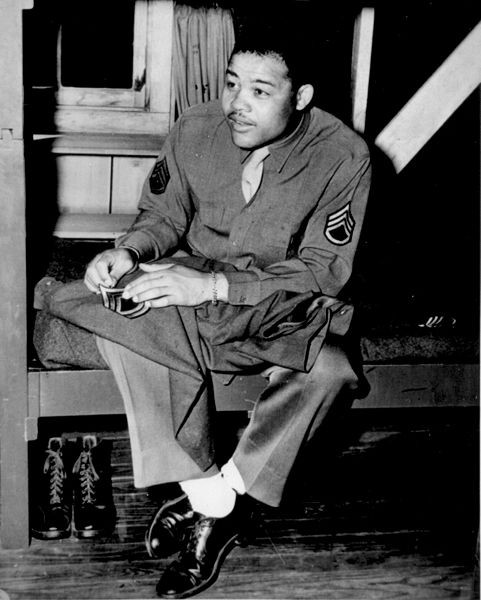

3. Joe Louis is best remembered as the "Brown Bomber," a boxer who possessed unparalleled physical powers that led him to defeat German Max Schmeling in a 1938 bout that united the country and came to symbolize America's resolve to stand firm against a growing Nazi presence.

But there was more to Louis than his punching power. He enlisted in the Army in January 1942, and the service employed the Alabama native to recruit blacks and to boost morale among all troops. Louis experienced racism while he was a Soldier but was grounded enough to look at the big picture, once remarking," Lots of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain't going to fix them." He also was conscious of his status and used it to better the lives of blacks serving in the military. Louis helped baseball great Jackie Robinson and others to gain entrance into officer candidate school. In 1952, the retired boxer, also an avid golfer, challenged a whites-only policy to play in a Professional Golf Association tournament being held in San Diego. He rounded up supporters and submitted a petition to the governor of California. The governor sided with Louis, and the PGA allowed him to play, making the Brown Bomber the first black to play in a PGA-sanctioned event.

4. When Africans arrived on the coasts of America in the early 1600s, much of their culture was systematically repressed by the institution of slavery and servitude. The Gullah, who live in communities situated along the sea islands of South Carolina and Georgia, are an exception. Aspects of its culture -- language, art, music and agricultural methods -- still exist today, making it possibly the only African culture left intact after the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade.

Unlike most African-Americans, the Gullah can trace its roots back to specific regions of Africa. For example, the Gullah's sweetgrass basketry is similar to coiled baskets made by the Senegalese, and cloth made from its strip looms bare resemblance to the cloth made by traditional strips looms used throughout Africa. Furthermore, many of the words used in Gullah communities are variations of words still used in Africa today.

How did the Gullah culture survive when virtually all others were extinguished? The history books provide a clear explanation: in the South Carolina and Georgia low country, as it is called, rice was the chief crop. To produce it, slaves were given some measure of autonomy during the rainy seasons due to harsh conditions and diseases such as Malaria and yellow fever. Slave owners tended to live elsewhere and left management operations up to slave overseers who were much more lenient in their management practices.

Today, the Gullah culture has somewhat evolved, but modern threats such as land development and economic conditions have forced some descendents to leave. Successful legislature to preserve and protect the sea island culture has given some measure of assurance the Gullahs will continue to survive.

5. Rosa Parks is often called the mother of the modern civil rights movement because she refused in November 1955 to yield her seat to a white on a segregated Montgomery, Ala., bus. Her act of defiance led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott that brought the public bus system to its knees and was the catalyst behind further protests and demonstrations that pushed the movement into high gear.

Though Parks' actions were momentous, they were not the first. In fact, at least three other women performed the same actions with less-celebrated results. The first, 27-year-old Irene Morgan of Baltimore refused to give up her seat to a white couple on an interstate Greyhound bus 11 years earlier in Middlesex County. The case went before the Supreme Court, and it ruled in her favor.

The case of Sarah Louise Keys followed. A private in the Women's Army Corps, she took an interstate bus from Fort Dix, N.J., headed toward her North Carolina home on the night of Aug. 1, 1952. At a stop in Roanoke Rapids, N.C., she refused to surrender her seat to a Marine and was eventually arrested and convicted. Her case was brought before the courts and the Interstate Commerce Commission. The latter ruled in 1955 that actions against Key violated the Interstate Commerce Act that prohibited segregation.

Another woman, Claudette Colvin, was merely a 15-year-old when she defied orders to give up her seat on a Montgomery public bus in March of 1955. She too was arrested and convicted and her case was also handled by the NAACP, which took it all the way to the Supreme Court in the Browder v. Gayle case. The court on May 11, 1956, ruled in favor of Colvin, but the NAACP decided not to promote the case because of Colvin's age and the fact that she was young, unwed and pregnant, which violated the social norms of the time.

6. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., Tuskegee Airman and first black general in the U.S. Air Force, didn't start his military career as an airman. The son of Brig. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the Army's first black general, earned a degree at West Point, underwent infantry training and followed his father's footsteps into the Buffalo Soldiers (24th Infantry Regiment). Most noteworthy was Davis' West Point experience in which classmates rarely spoke to or dined with him and where he roomed alone for the duration of his four years there. The academy tested the depths of Davis' commitment to his cause, but he emerged more determined to prove his worth and would go on to command the Airmen in World War II. More than 30 years after Davis' retirement, President Bill Clinton acknowledged his sacrifices, promoting him to the rank of four-star general. "General Davis," he said, "is here today as living proof that a person can overcome adversity and discrimination, achieve great things, turn skeptics into believers; and through example and perseverance, one person can bring truly extraordinary change." Davis died in 2002.

7. The Tuskegee Airmen was arguably the most well-known black military unit of World War II. Comparatively, the Army's 761st Tank Battalion and its exploits are quite obscure. Called the "Black Panthers" way before the militant group adopted the name, the 761st became the first black tankers to fight in any war, enduring 183 consecutive days of operational employment in the European theater. Much of that time was marked by intense combat, and the Panthers often fought alongside white infantry units even though the armed forces were still segregated. Jackie Robinson was a member of the 761st prior to being kicked out for refusing to give up his seat on a bus during training. Another member, Staff Sgt. Rueben Rivers, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1997. Twenty-four Panthers were killed and 88 were wounded during the war. The unit's motto was "Come Out Fighting."

8. In the annals of African American history, there have been many efforts on behalf of blacks to escape their conditions in America. One during the American Revolution, centered on an offer by the British to grant freedom to any blacks who would join its ranks. Roughly 100,000 freemen and slaves moved to the British side and many wound up in southeastern Canada after the war. Furthermore, thousands of slaves who used the Underground Railroad to escape bondage also found their fates in Canada. Today, thousands of black Canadians can trace their heritage back to the United States.

Another effort of note, organized by the American Colonization Society starting in 1816, was based on the premise that slavery couldn't be sustained in America and blacks could lead better lives in Africa. With the help of the U.S. government, ships carrying mostly free black emigrants began sailing for the shores of Africa in 1821, eventually establishing the country of Liberia. The voyages continued until the 1860s. By that time, more than 11,000 blacks had carved out a civilization in the land of their ancestors. J.J. Roberts, who spent part of his boyhood in Petersburg, Va., became Liberia's first president in 1847.

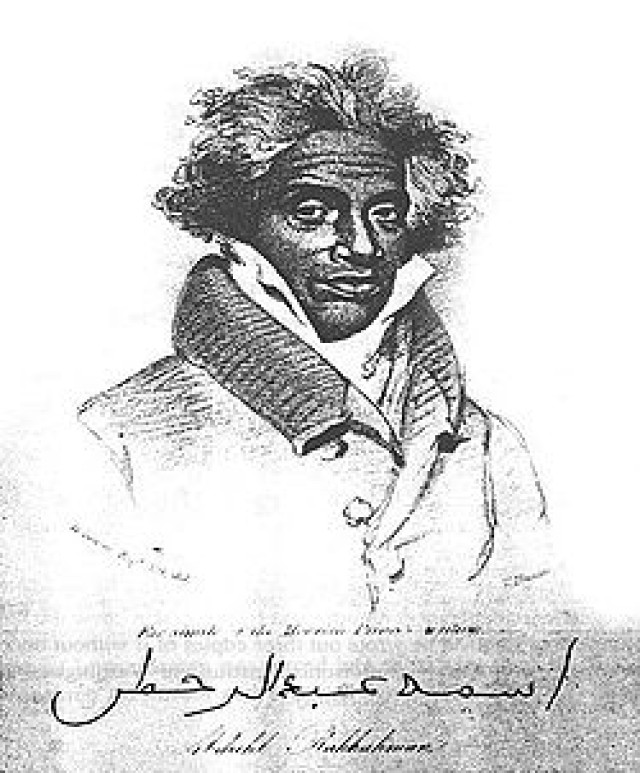

9. For the most part, slavery destroyed the ancestral lineage of African- Americans by the millions. As a result, many find it is quite difficult to trace family lines beyond three or four generations. That's not the case for the descendents of Abdu-l-Rahman Ibrahim Ibn Sori or Abdul Rahman. An African prince, he was brought to America in 1788. His talents were such that he became a trusted overseer of slaves on the Natchez, Miss., plantation of Thomas Foster. During his time at the plantation, Abdul- Rahman became acquainted with a Dr. John Cox, a surgeon who was aided by Abdul-Rahman's family after he and crew members were shipwrecked off the coast of Guinea. Cox lobbied for Abdul-Rahman's release to no avail. Abdul-Rahman joined the effort as well, writing a letter to Senator Thomas Reed in Washington. The letter, written in Arabic, was forwarded to the U.S. Consulate in Morocco. The sultan of that country read the letter and requested Abdul-Rahman's release. Abdul-Rahman was eventually released and began a campaign to raise funds to purchase the freedom of family members. In the end, he could purchase only two of his nine children. Abdul-Rahman did return to Africa by way of the American Colonization Society but never saw the remaining family members. In 2006, the descendents of Abdul-Rahman held a reunion that was made part of a PBS documentary about the prince's life. Curiously, several of his relatives carry either the first or last name of "Prince."

10. The first Southern reading of the Emancipation Proclamation took place at the Emancipation Oak on the campus of what is now Hampton University in Hampton, Va. Located three miles from Fort Monroe, the 98-feet-in-diameter Southern Live Oak is the place where contrabands were taught during the Civil War. The reading of the historical document took place there in 1863. The tree has been named one of the 10 Great Trees of the World by the National Geographic Society.

Social Sharing