WIESBADEN, Germany - Visitors to the German cities of Wiesbaden, Frankfurt and Berlin find it hard today to imagine what the country resembled after the massive destruction of World War II.

But even as life slowly returned to some semblance of normalcy back then - and citizens began the arduous task of picking up their lives and rebuilding amidst the rubble - a Cold War was already simmering between former allies.

A major flashpoint in the 50-year confrontation between the powers of the East and West occurred when the Soviet Union, led by Joseph Stalin, began a nearly yearlong blockade of Berlin in June 1948, attempting to starve more than two million citizens and thousands of Allied troops. The siege included blocking all access to Berlin by land and water, and eventually cutting off power to the city's west.

The Allied response was immediate. What became known as the "greatest humanitarian airlift in history" was quickly launched to supply the people in the American, British and French sectors of West Berlin with needed coal, food, medicine and other supplies.

An air bridge - or "LuftbrAfA1/4cke" as the Germans called it, and Operation Vittles as the airlift mission was unofficially labeled by Brig. Gen. Joseph Smith, Wiesbaden post and airlift commander - featured non-stop flights to the beleaguered city, delivering tons of supplies around the clock. Flying from airfields in Wiesbaden, Rhein-Main near Frankfurt, Celle, Fassberg and other northern Germany towns, the Allies eventually transported more than 2.3 million tons of goods in more than 277,000 flights in and out of Berlin before the Soviet stranglehold was broken and the siege ended May 12, 1949.

A pilot remembers

John Dear spent the war years in Texas teaching fellow pilots as an instrument instructor. The airlift gave him a chance to contribute closer to the cause.

"During the Berlin Airlift, I started out in Rhein-Main," Dear said. "I was one of the first ones there to fly into Tempelhof (airport) in Berlin."

The now 90-year-old airlift veteran spent 26 years in the Air Force, including a stint with Headquarters U.S. Air Forces Europe in Wiesbaden from 1961-65. While shuttling troops from San Francisco to Guam, he was given 24 hours notice to report to Germany. What started out as a 30-day temporary duty assignment quickly stretched into approximately 150 missions and eight months of flying in and out of Berlin, Rhein-Main Air Base and an airfield in the British Sector at Fassberg.

"It was a real emergency," said Dear, who lives in Bell, Fla. "We were all proud of (President) Harry Truman. He's the one who stopped the Russians in their tracks."

Dear said serving as an instrument instructor during the war years paid off during the airlift as pilots frequently were called upon to rely on their ground control approach support when landing in Berlin because of low visibility due to fog and rain.

He remembers how difficult it was to make initial flights into Tempelhof via two-engine C-47 Skytrains. Structures stood in the way of the flight path. An aircraft's landing gear sometimes actually scraped roofs, which forced the pilots' route into the airport by having them cut power suddenly and braking before running out of landing strip. "Several of my friends couldn't stop in time and ran out of runway," Dear said.

"The radar guys did a beautiful job," he recalled, adding that on at least one flight he wasn't able to see the runway until 20 seconds before touching down.

After initially flying out of Rhein-Main AB, Dear moved north out of the American sector (Germany was still divided into Allied areas in 1948) and began flying four-engine C54 Skymasters, hauling mostly coal shipments from the Royal Air Force-controlled airport at Fassberg to Gatow and Tempelhof airports in Berlin.

With flights eventually arriving at three-minute intervals in Berlin, Dear said airlift planners such as Maj. Gen. William Tunner eventually decided that during bad weather - rather than having aircraft circle during a missed approach and "stacking" at ever higher altitudes for a second attempt - pilots were instructed to return home. "If we missed our approach, we just took our coal and went home and got ready for another mission."

Fellow Germans assist

Retired German engineer Gustav KochendAfAPrfer recalls how an ever-increasing number of military members, civilian technicians and planes began arriving at the air base in Wiesbaden-Erbenheim as the airlift stretched into its eighth week.

KochendAfAPrfer, who was an engineer with the Air Installation Office, joined the airlift effort after a Berlin-bound airplane loaded with steel planking failed to take off. Ground crewmen, many of whom were former German prisoners of war and displaced persons living in tents on the airfield, had misjudged the weight of the metal, which was meant for constructing runways, streets and other construction projects. Consequently, engineers - using a slide-rule device known as a load adjuster - were called in to help measure every load and to properly judge placement in the aircraft.

Although the Wiesbaden native, who started working at the airfield in 1947 at age 24, admitted he initially "had no love of Americans" after being harshly treated by Allied guards while a prisoner of war, the airlift changed his views. "With the airlift," KochendAfAPrfer said, "my ideas changed. Here was something good being done."

As the airlift continued, KochendAfAPrfer became involved in several projects to improve the working environment for loaders and mechanics servicing the planes. One such effort: building covered ramps from which crews could do repair work outside, regardless of the weather. The canvas-covered "stairs on wheels" were so popular in Wiesbaden that KochendAfAPrfer was called to Rhein-Main to explain how to build the mobile workstations. During his presentation, it became obvious that Americans didn't understand the metric system, so he changed the plans to feet and inches.

Even before the airlift began, Wiesbaden Air Base was a busy place where aircrews frequently trained. During the airlift, when fog and bad weather grounded flights, KochendAfAPrfer said the base became crowded with parked aircraft.

"The big advantage at Wiesbaden-Erbenheim was that the German personnel - from cooks to engineers - were already in place before the airlift," said KochendAfAPrfer, who continued to work and improve the installation in the years following the airlift, including such projects as helping to build the airfield control tower and water systems.

A teacher's personal connection

For Wiesbaden High School teacher Christine Taylor, the airlift simply was another part of surviving the lean years during and after World War II for her parents.

Her father was a former Polish soldier who escaped from German capture only to be retaken and transported to Berlin to work as forced labor. Her mother endured life in the devastated city as a teen and young adult. The Berlin blockade was the final straw that convinced them to leave German to seek refugee status in the United States.

"My mother, who will turn 84 this year, told me she was at a performance of 'Madame Butterfly' in Berlin when they stopped the production to say the war had begun," said Taylor.

As for her father, "no one else in his family survived the war ... he worked for the International Refugee Organization in Berlin after the war because he spoke so many languages."

While her father "never talked about the war," and the years following, her mother described "just how awful it was - tearing everything down that was (made of) wood to use as fuel" and how her mother's father died of malnutrition before the war was over. "She always had stories about what they had to eat - digging for roots for soup." Her mother also described how people, desperate for fuel, chopped down trees throughout the city.

The winter of 1948/1949 was especially hard for the Berlin population.

During the blockade, Taylor's mother climbed aboard Russian train cars - which had to pass through the Western sector at night - to steal coal. Neighborhood men discovered how to work track signals to stop the trains. When the Russians learned of the thefts, they patrolled the rails with dogs to keep desperate Berliners away.

"They were contained in the city and trying to survive," Taylor said, referring to people trapped by the blockade. "It was so hard; that's what made them want to get out."

After Taylor's parents meet and married in Berlin, they emigrated to the United States, arriving in New Orleans on Labor Day 1949 aboard a troop carrier, and eventually ended up working on a plantation in Shreveport, La.

Taylor, who was born in 1951, regularly sent "care packages" to family members left behind in and around Berlin even years after the airlift had ended.

"Growing up, I remember we always had an emergency suitcase packed - my mom called it a boogie bag - in case we had to leave in the middle of the night. They had lost so much money during the war years that she would never again invest in the government."

Sixty years later, Taylor is sharing her memories with her Wiesbaden students as she assists them on a special Berlin Airlift Anniversary project to be entered in a competition sponsored by the American Consulate and city of Frankfurt.

Students researched the Berlin Airlift, putting together a Website showcasing their class work and historical insights. They also made parachutes with chocolate - modeled after those originated by famed Candy Bomber Lt. Gail Halvorsen during the airlift - which will be sent to a German school in Berlin overseen by one of Taylor's in-laws. "We're building bridges between Wiesbaden High School and the school in Berlin, between what the Allies did during the Berlin Airlift and what's being done in Iraq today, between the past and the present, Germans and Americans," she said.

(To view the students' airlift website, visit the U.S. Army Garrison Wiesbaden's Berlin Airlift home page - http://www.usaghessen.eur.army.mil/BA/BA.htm - and click on the "Wiesbaden High Berlin Airlift Website" link on the lower left side of the page)

A child in Berlin

Traute Grier experienced the war years firsthand as a child in Berlin. Recalling the hardships of the post-war years, Grier remembers how she and her mother (her father died during the war) put mustard on their bread or fried it in sugar to make a meal. Another staple was potatoes, she said, as "one day we had soup with potatoes and the next day it was potatoes with soup. My mother worked in a school, so we had a little food."

"We were afraid when the Soviet blockade began; the Russians were not our friends," said Grier, who has long been a naturalized American citizen after having married an Army dentist in Berlin and living in the States for many years. "We were afraid the Allies would leave."

"(For) a child during the blockade, the worst thing was having no lights," said Grier, who lived in the Neu KAfAPln section of Berlin and was born in 1932. "With only up to four hours of electricity a night, people got used to cooking and performing other chores at home in the wee hours of the night. As children, we always had a fear that someone was waiting for us in the dark."

Grier said she will never forget the sound of planes arriving every few minutes with needed relief for Berlin.

"It's sad that the story about the Berlin Airlift is being forgotten," laments Grier, who now lives in the town of Oberursel, just north of Frankfurt. "If it hadn't happened, and the Allies had left, Germany would have fallen to the Russians and sunk into the East zone. And then what would have happened to Europe' That didn't happen thanks to Gen. (Lucius) Clay (U.S. military governor of Germany) for standing fast and making sure the airlift occurred and was a success.

"Children these days don't understand that if things had gone wrong in 1948 and 1949 how different the world would be today."

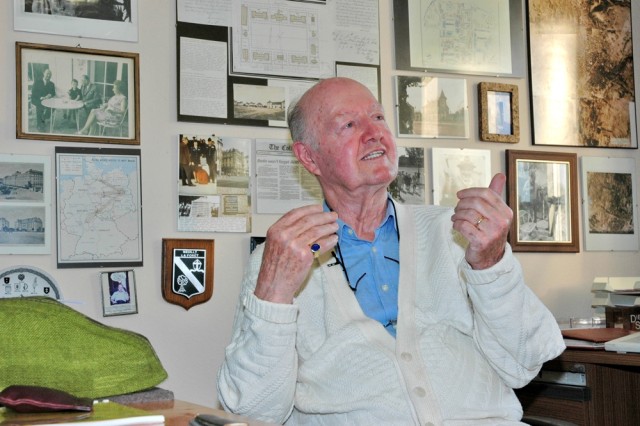

Author shares stories

For historian John Provan, coauthor of the book "Berlin Airlift - the Effort and the Aircraft," an encounter with a legend during the 1988 Rhein-Main AB open house inspired him to delve deeper into the background of the massive humanitarian air mission.

During the open house, Halvorsen, wearing his flightsuit, visited Provan's display on the zeppelin period. As he stood there, another man stopped to ask Halvorsen if he was the Candy Bomber. "When Gail said yes, the guy broke down crying; he was one of the children who got the candy in Berlin," Provan said. "I then realized that this topic and all the stuff we've done in the years since World War II are being forgotten."

Provan, a 1974 graduate of Kaiserslautern American High School, added, "That's (why I) started gathering up materials from those leaving (as bases continued closing after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989).

Provan believes Halvorsen's innocent gesture to toss chocolate to the children of Berlin became a symbol of American goodwill and the Allied willingness to do whatever it took to ensure freedom and democracy in Europe.

"That probably did more good than the speeches of a whole bunch of politicians put together."

While researching the airlift for his book and for various exhibits he displays in Germany, Provan came across many unique stories about the massive effort. One concerns Clarence the Camel, the mascot of the Neubiberg-based 525th Fighter Squadron that had trained in Tripoli, Libya. When the 525th FS joined the airlift, unit members delivered a camel to Berlin for children in the land-locked city to enjoy.

Besides the airlift itself, Provan also studied Operation Kinderlift - an airlift of children that ran from 1953-57, giving some 12,000 children the opportunity to leave an impoverished Berlin for summer vacations in West Germany, courtesy of USAFE and the Red Cross. "The children were flown from Tempelhof and were 'adopted' for the summer, many by American families," Provan said.

Remembering the fallen

Road signs on Wiesbaden Army Airfield today pay tribute to 32 U.S. servicemen who sacrificed their lives during the airlift.

Ensuring that those who died are remembered has long been a personal mission of D-Day veteran and historian Ronald MacArthur Hirst. The 84-year-old military retiree, who served with the Air Force at Wiesbaden's former Lindsey Air Station, spent years researching and organizing such groups as the British Berlin Airlift Association. In doing so, he has made a personal connection with families of the fallen, letting them know their loved ones are remembered.

With the closing of Lindsey AS in 1993 and Rhein-Main AB in 2005, Hirst made sure installation signs paying tribute to those killed during the airlift and in other air crashes made their way to family members - or found a new home on Wiesbaden Army Airfield.

"There must be some form of remembrance for the people who have given their lives," said Hirst.

Explaining that while the exploits of one pilot, referring to Halvorsen, have captured the attention of most people who know anything about the Berlin Airlift, Hirst stressed that it is important to remember all who contributed to the phenomenal effort to save the starving population of Berlin.

"I don't think it's publicized enough ... what these guys went through. I really don't think people realize what that airlift was all about."

After noting what he called "decrepit street signs on Lindsey" while serving as an Air Force action officer, Hirst approached the base public affairs office to learn more about the men behind the names on the signs, which had been dedicated in 1949. "Over the years," he said, "I found out exactly who these guys were."

His persistence also helped to identify servicemembers who died during the airlift but were not included among those memorialized. After he questioned why only one sign for them was erected on Wiesbaden Army Airfield in 1994, it was decided in 1995 to recognize each fallen American with his own sign - 32 in all.

Upcoming airlift observances

The city of Wiesbaden and U.S. Army Garrison Wiesbaden will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Berlin Airlift from June 26-29. With a special exhibit at the Wiesbaden Kurhaus - which served as the American Red Cross Eagles Club during the airlift - and an open house at Wiesbaden Army Airfield on June 29, visitors young and old can encounter living history ranging from witnesses, testimonials, aircraft and much more.

Visit the USAG Wiesbaden's Berlin Airlift Website at http://www.usaghessen.eur.army.mil/BA/BA.htm

for more news about the Berlin Airlift celebration: parking, events, media coverage and other ceremonies in Wiesbaden as details take shape.

Social Sharing