There's no place like… the dining facility? While the culinary accomplishments of the U.S. Army are not typically associated with gourmet fare, the Army has been feeding troops since the Revolutionary War. As part of its mission to feed its troops, the Army has served up Thanksgiving dinner all around world for more than a century.

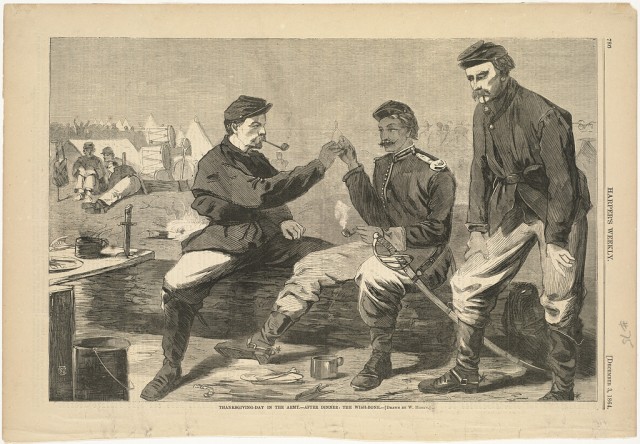

Humble Beginnings

President Abraham Lincoln and Sara Josepha Hale, editor of Godey's magazine, are responsible for the contemporary manifestation of Thanksgiving. Though based on an actual historical event, the modern celebration was invented in the 19th century. The holiday evolved from a regional day with modest edible offerings into a celebration of middle-class America and bountiful food. According to social historian Elizabeth Pleck, as the Civil War divided a nation, Thanksgiving sought to instill a cohesive identity, no longer associating the day with just a New England celebration, but encompassing all Americans. In her 1999 work, "The Making of a Domestic Occasion," Pleck argued, "…nostalgia at Thanksgiving was a yearning for a simpler past" located in a pastoral and old-fashioned landscape. The "New York Times" article "From Sheridan's Army" that appeared Dec. 1, 1864, lauded the hearty servings of turkey, goose, and duck as well as the side dishes prepared for the Union troops "real old-fashioned Thanksgiving dinner."

The Frontier

"The Great Source of Amusement: Hunting in the Frontier Army" illustrates where soldiers spent Thanksgiving made a big difference in what they ate for dinner. In his 2005 article on the topic, James E. Potter outlined the way hunting was a common pastime for both enlisted and officers stationed in the American West. "By supplementing the diet and providing recreation," Potter argued, "hunting improved the lives of frontier Army soldiers." In the 1860s and 1870s, even if enlisted troops lacked the time in their days to enjoy the sporting aspects of hunting, they were able to benefit from a culinary standpoint. The holiday season, especially, was the time hunting became more urgent. While forts on the east coast were able to benefit from railroad transport of a wide variety of foods, those out west had to rely on their own devices to create more lavish holiday meals. "Boiled beef and salt pork" were the standard Army fare, and no one wanted to subsist on these at Thanksgiving. In 1874, a correspondent from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, reported that a hunting party of 12 men provided the canteen with 156 turkeys, while still another group of officers provided 60 additional turkeys, five deer, two wildcats, and a bear. At Fort Lyon, Colo., a few years later, the 1871 Thanksgiving feast centered around buffalo.

Progressivism and the First World War

Celebrating America as a nation was a focal point of early Thanksgiving festivities. During World War I the holiday took on an additional role of helping to assimilate the wave of newly settled immigrants to the United States. One way individuals adopted a collective identity was though serving together in the Army. World War I is not often remembered for its impressive dietary highlights, but menus from this era survived and list a wide variety of foods that were far more than basic rations of beef and beans. Major Louis C. Wilson of the Quartermaster Corps wrote in 1928 "not only must the Soldier be fed, but fed properly!"

World War II

A unique aspect of World War II rationing meant food went to the military first, and to the open market for civilians second. The Under Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson, wrote in The Quartermaster Review in 1945, the Army's food requirements accounted for 12 percent of the total food supply of the county. The "Signal Corps Message" a military newspaper printed at Fort Monmouth, N.J., reported in the fall of 1944, the War Food Administration restricted the sale of turkeys to civilians until the Quartermaster Corps had fulfilled its requirements. Poultry production was reportedly so great, however, that there would not actually be a need to restrict the sales. The military needed "plentiful helpings of white meat and dark meat for every man in the service." But the Army didn't only serve men.

The Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, or WAACs, at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, enjoyed a "gala holiday for 7,600" on the Army post. The "Register," the local newspaper, printed Nov. 27, 1942, reported many WAACs received boxes of gifts and non-perishable food from relatives back home. This was the first Thanksgiving in the history of the women's army, and offers a unique perspective on a holiday typically associated with women spending hours preparing a meal. In addition to the thousands of WAAC Soldiers who celebrated Thanksgiving on the Army installation, many civilian guests joined them.

Consumer studies professors Melanie Wallendorf and Eric J. Arnold attest that the holiday celebrates "not just a moment of bounty, but a culture of enduring prosperity." Their work on this phenomenon, "Consumption Rituals of Thanksgiving Day," illustrates that while Thanksgiving might be a uniquely American holiday, it was well-known in Europe as a major event. During World War II, the British hosted a celebration for U.S. troops in Westminster Abbey!

The Cold War Era

Maj. Gen. Lawton, Signal Corps officer and commander of Fort Monmouth, expressed his gratitude in 1953 because "this year has marked the cessation of active hostilities in Korea and the return of thousands of Americans to their homes and families." The installation expected a large number of soldiers, upwards of 5,000, to vacate the base during the Thanksgiving weekend. Elaborate meals were available for those individuals remaining on post: the soldiers were able to enjoy dinner for free, while guests of service members and Department of the Army civilians were able to purchase dinner for a nominal fee. "The Monmouth Message" reported that all Thanksgiving dinners could be purchased for less than $2.50 per person.

Feeding the Modern Army

Spc. Scott Grohowski recalled Thanksgivings he's had during his enlistments with the armed services. He'd had Thanksgiving dinner on the USS Essex (LHD-2) as a Marine, in Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, and plenty of bases in between. "It was some turkey and standard Thanksgiving day sides on the Essex, with a lot of crab and lobster," Grohowski said. "On Bagram, it was a big to-do at the chow halls. Fresh carved turkey, roast beef, ham at their own carving stations; plus all the sides and then some. It was huge, and definitely seemed like they put a good bit of effort into it." Compared with some of the bases in the United States, he thought the meal at Bagram was more elaborate and tasted better, too.

Karen Stowers, a staff writer for the Army Times reported that in 2010, 144,854 pounds of turkey was consumed in Iraq for Thanksgiving alone. The Defense Logistics Agency supplied more than 270 dining facilities with Thanksgiving fare in 2011. Menus need to be planned months ahead in order to make sure all deployed troops are able to have the special meal. Whether prepared in Garrison facilities or at mobile kitchens in remote sites, officials use supply chain infrastructure to provide food to service members as well as State Department employees overseas.

The mythology of tradition is strongly linked with Thanksgiving; as an American holiday, the notion that all citizens celebrate it in the same way is a prominent part of the narrative. Not only is similarity stressed but the idea that contemporary Americans are eating the same meal as their Pilgrim predecessors did centuries earlier. In "The Invention of Tradition," Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger categorize this type of behavior as "invented tradition," or a ritual implying continuity with the past, even though the continuity might be overstated. It's vital to keep in mind, however, that this phenomenon is not something negative. The invention of tradition is a way to connect to the past through a shared history and borne of the desire to form national identity and unity in the present. It happens with all holidays and is reflected in customs, style of dress, food prepared, and activities. The main aspect that sets Thanksgiving apart is that it is a comparatively recent holiday and there is ample historical documentation detailing how the holiday evolved.

This Thanksgiving, regardless of where you are or what's on the table, remember that we all have a lot to be thankful for.

Social Sharing