Fort Huachuca, AZ. - In June 1944, when Comanche Indian Cpl. Charles Chibitty landed on Utah Beach in Normandy, his first radio message was to another Comanche on an incoming boat. He transmitted it in his native tongue. In English, the message was: "Five miles to the right of the designated area and five miles inland, the fighting is fierce, and we need help." At 23, he was already a veteran code-talker. There were a total of 14 Comanche who hit the beach that day. Two were wounded, but they all survived.

Chibitty's journey to that moment in time began in the Wichita Mountains north of Lawton, Okla., in 1921. He grew up speaking his tribe's native language. A descendant on his mother's side from Chief Ten Bears, Chibitty's name, in Comanche, means "holding on good." That name would be important in the coming years as he worked to hold on to his own identity.

As a child, Chibitty attended the Fort Sill Indian School, Fort Sill, Okla., where he was punished if he spoke Comanche. The school was one of many government-run boarding schools established to assimilate Indian children. The Smithsonian Institution's exhibit, "Native Words, Native Warriors," explains that the boarding schools "were founded to eliminate traditional American Indian ways of life and replace them with mainstream American culture. Initially, the government forced many Indian families to send their children to boarding schools. Later, Indian families chose to send their children because there were no other schools available." The schools used humiliation, punishment and coercion to separate the children from their native religion, language and traditions.

Chibitty attended high school at the Haskell Indian School in Lawrence, Kan. His native language was not forbidden there, but he was schooled in a strict, militaristic style. Far from his family, Chibitty and his classmates exchanged traditional clothing and hairstyles for uniforms and crew cuts. They became accustomed to marching drills, following orders and strenuous athletics. While at school, he heard the rumors of war and learned that the military planned to organize a native-speaking unit. During Christmas break in 1940, Chibitty asked for and received his mother's permission to enlist.

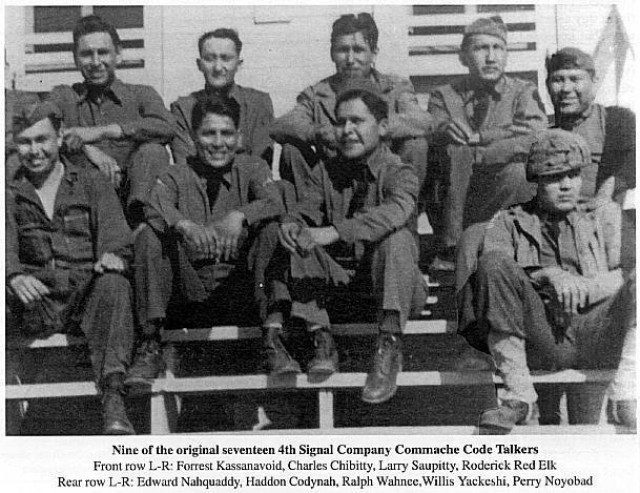

Pvt. Chibitty easily transitioned into military life. He joined 16 other Comanche sent to Fort Benning, Ga., for basic training and then to the Signal School at Fort Gordon, Ga., for training as radio men. Their primary mission was to create a coded language the Germans could not decipher. They created a military dictionary of 100 words from their native tongue. If a word they needed did not exist in Comanche, they made up a term from other Comanche words to fill that need. Their code was never broken. In addition to D-Day, Chibitty participated in fighting at St. Lo, Hurtgen Forest, the Battle of the Bulge and the rescue of the "lost battalion."

During World War II, Cpl. Chibitty earned five campaign battle stars and received a cavalry officer's saber from his tribe, an honor comparable to the Medal of Honor among the Comanche. But it took nearly 45 years for the government to honor the code-talkers for their contributions. In 1989, the French government recognized the code-talkers of both world wars. Ten years later, Chibitty received a Knowlton Award from the Military Intelligence Corps Association at the Pentagon's Hall of Heroes. Somewhat uncomfortable with the attention, he focused on his Comanche friends who served with him. Holding back tears, Chibitty commented, "I always wonder why it took so long to recognize us for what we did … They [his deceased comrades] are not here to enjoy what I'm getting after all these years. Yes, it's been a long, long time."

Chibitty "held on good" to his Native American roots, even when he was punished for doing so. His Comanche language was both a source of comfort to him and an asset to his military mission. Throughout his life he remained closely connected to his native culture, dancing in gourd dances to honor veterans and in pow-wow contests throughout the country, teaching his beloved Comanche language to anyone who was interested. He became a respected chief of his people, inspiring new generations to respect their traditions and preserve their culture. For this, and for his exceptional contributions and sacrifice made during the war, America owes him her deepest gratitude.

(Author's note: Much of the information in this article on Chibitty was taken from The Smithsonian Institution's Museum of the American Indian exhibit "Native Words, Native Warriors." For online access, go to http://nmai.si.edu/education/codetalkers/html/. A traveling version of the exhibit is being shown in conjunction with "Navajo Code Talkers, Photographs by Kenji Kawano" at the Heard Museum in Phoenix through March 31. For information, go to http://www.heard.org/visit/index.html.)

Fort Huachuca celebrates Native American Heritage

Fort Huachuca's Native American Heritage Month observation will be held on Nov. 14, with two separate events:

Native American Heritage Month at Thunder Mountain Activity Centre takes place at 11:30 a.m., with a brief presentation on Native American Code Talkers, cultural demonstrations and food tasting.

The MI History Office presentation at takes place in Fitch Auditorium in Alvarado Hall, 2:30 -- 3:30 p.m., by Dr. William Meadows, historian, and author of "Comanche Code Talkers of WWII." Meadows will provide an in-depth look at the code-talkers from many tribes who served in both world wars.

For more details on this presentation, call the History Office, 533.4113 or 538.6638.

Social Sharing