WEST POINT, N.Y. (July 19, 2012) -- The U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., is looking for a few good Soldiers.Soldier admissions officer Maj. Ryan Liebhaber has 85 slots for active-duty Soldiers and 85 slots for reserve-component Soldiers in every class.

One of the hardest parts is convincing Soldiers, who must be single with no dependants and between 17 and 23 years old, that they might have a shot at getting in to a school that has educated presidents and four-star generals. Liebhaber targets Soldiers who have high Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery and General Technical test scores, reasoning they would also do well on the SAT or ACT.

Many Soldiers are accepted to the prep school first. It's not "the B-team," it is just a way to set them up for success. And the prior-service cadets who've attended said that while they may have been initially reluctant to spend an extra year in school, it pays off.

"After being out of school for four years, the prep school helped me a lot," said 1st Lt. Samuel Aidoo of the class of 2010. "It got me back into the mindset and routine of doing school work again, thinking critically in the application of mathematics and communicating effectively through writing. When training to become as tactically proficient as possible, Soldiers tend to place some of these skills on the back burner. Luckily for us, the prep school is here to help recover those long-stored skill sets."

An Army Ranger with two deployments under his belt, the former sergeant learned about the Soldier admission program from West Point graduates at Ranger School, and as he was trying to decide what to do when his enlistment ended, he kept thinking about how much he admired those officers.

"I was an 18-year-old combat veteran. To the second lieutenants I was a hero," he wrote. "They were my heroes. I became very close to many of [them] and I shared my ambitions of going to college with them. That's when they began talking to me about West Point."

"I wanted to stay in the Army so that was a big plus. But I think the greatest discriminator between USMA and ROTC was that most of my officers and mentors, gentlemen I had great respect for, graduated from this institution. I could only hope to be half the leader they were, and I decided West Point would help me."

Cadet Alexander Brammer, the prep school battalion commander last semester, had a similar experience. Also a Ranger and a three-time combat veteran, he too was intrigued by West Point alums while at Ranger School. After being offered direct admission to the academy, he was injured during a parachute jump and unable to participate in Beast (cadet basic training). If he had waited a year, he would have exceeded the age limit.

Fortunately a loophole enabled the former sergeant to swear in, then medically withdraw and attend the prep school. He will be 27 when he graduates, but said the delay was a blessing in disguise. "I was thrilled to have the opportunity to go to West Point at all. The prep school helped me get back into the academic mindset, but more importantly, it gave me a year to decompress. I have a lot of respect for the prior-service cadets coming straight into West Point from combat units."

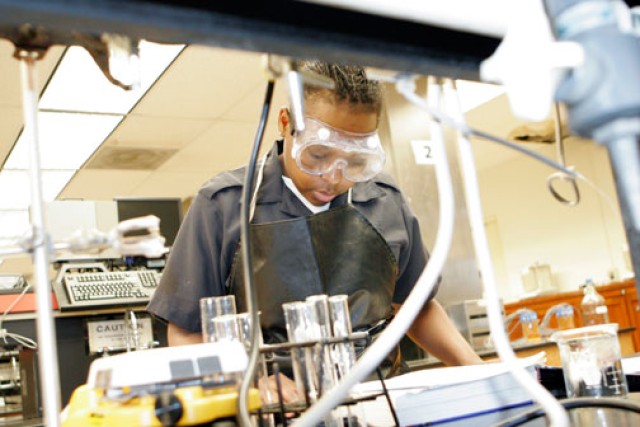

Former Spc. Brandi-el Cook is one of those cadets. She only had about two weeks to redeploy from Iraq, reintegrate and take leave before reporting to West Point in 2009.

"I think I still had sand in my hair when I got here," she laughed, explaining that she completed her entire application downrange.

It took almost a year and involved many late-night phone calls and faxes as she tried to track down her records and test scores. She had already completed two and a half years of college and had to start back at square one per USMA requirements, but added, "There's something about it that's absolutely worth it."

Her first reaction when arriving at the academy, however, was that she wanted to return to Iraq, as West Point is a shock academically and socially. Although basic training at West Point is run by cadets who are usually years younger with no real experience, it's harder than one might expect, and also quite humbling.

"You go from being an E-5 to being basically a nobody and it's tough. You have to exercise humility. You have to have the goal in mind of graduation. You have to be focused on that and understand that you're going to have to pay your dues just like everyone else," said now 1st Lt. Tyler Gordy, class of 2010, adding that it took about four months for him to adjust.

As the first captain (the highest ranking cadet) last year, Gordy was in charge of about 4,400 cadets. He represented the Corps of Cadets at meetings and relayed intent to subordinate cadet leaders; greeted dignitaries like the president, cabinet secretaries, celebrities and even royalty; and served as the master of ceremonies at parades and dinners. His active-duty combat experience helped him, but sometimes his academics had to take a back seat to his other responsibilities.

Like many prior-service cadets, Gordy got academic help from younger cadets, most of whom spent their entire high school careers earning grades good enough for West Point. In turn, the prior-service cadets gladly helped their classmates learn the finer points of military bearing and culture.

"Being prior service has taught me how to deal with stressful situations. It helped me mature. I've used my experience in the Army extensively at West Point. You've had some time out in the real world. You know what's important to you. You know what you want to do with your life, so when you get to West Point, you're not playing around. You're ready to get serious, get to work," he said.

"Combat changes people," added Aidoo. "You learn to appreciate life more after seeing it disappear before your eyes. Combat matured me. I think I bring a lot of that maturity to my class work. Prior to the Army, I didn't have that that sort of appreciation for education."

But it was also difficult to deal with combat memories while at West Point, he continued. No one from his unit was there to understand why he might be sad on a particular day, and combat veterans have the usual reintegration challenges in addition to schoolwork. Cook agreed; she doesn't sleep well and, thanks to several mortars and improvised-explosive devices, doesn't like loud noises. She said the counselors at West Point are more equipped to deal with college-student anxiety than combat veterans and that many of her fellow cadets simply don't understand. They can't.

"Because they haven't been there, they don't really understand combat," Cook, who is involved with the prior-service club, said. "They don't understand it really can affect people. PTSD is always a joke. It's always about how weak these people are. I just wish they could see some of the things that I've seen, or go to the places that I've been and know the people I know, and understand it's not a joke."

"The biggest challenge for me has been knowing that my friends are still at war and I am sitting in calculus class," Brammer added. "I have to actively keep myself motivated and focused, and keep my eye on the ultimate goal. It would be very easy to withdraw from West Point and go fight as an enlisted guy again, but it would be selling myself short. Remembering that and keeping a good attitude is the hardest part."

That's all offset by opportunities they could never have dreamed of before. Cook's former commanding general is a West Point alumna, and Cook said she was honored to have lunch with her, one-on-one, and amazed that the general wanted to know how she liked West Point. She was also thrilled to have the opportunity to travel to Ghana on a summer training trip.

"If you look at your life and you think to yourself it's either not exactly where you want it or could be better, there's no option (but to consider West Point)," Cook said. "There's no option if you want great career options and you want a degree. If you want to be an officer -- even if you don't want to be an officer -- I still say consider it, because the opportunity that this institution provides is unparalleled."

"The Army pays for you to be a better person. The Army says, 'I want you to be the best you that you can be for us. Come work for me and be amazing. And we're going to pay for all of the training that makes you that person.' Why wouldn't you want to take advantage of that?"

A Soldier's guide to applying to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point

-- Visit http://www.westpoint.edu/admissions/SitePages/Pros_Cadets_Soldiers

to check the requirements. Read through the rest of the USMA website to see if you qualify and if the school might be a good fit for you.

-- Try to find West Point alumni in your unit that you can ask about the school.

-- Discuss your ambition with your chain of command, and ask your company commander to complete the USMA commander's endorsement.

-- Contact Maj. Ryan Liebhaber (ryan.liebhaber@usma.edu), the Soldier Admissions officer, with any questions.

-- Improve your packet by taking or retaking the SAT or ACT (you'll need a minimum score of 1000 on the SAT or an ACT score of 20; both tests are free at post education centers), and possibly attending a few college classes. You can use the website www.march2success.com to help you prepare for the SAT and/or ACT.

-- Start a file in the fall a year before you would like to begin school at http://www.westpoint.edu/admissions/SitePages/Apply.aspx. If you pass the initial screening and meet the minimum USMA requirements, you'll receive access to the full application.

-- Complete your application, including fitness assessment, three candidate essays, three evaluations from your chain of command and a formal nomination from your company commander. You'll also need your transcripts, test scores and a medical screening.

-- Next year's application deadline is Feb. 28, but West Point has a rolling admissions process, so the earlier you apply, the better your chances of getting in. There is only one application for both the academy and the U.S. Military Academy Preparatory School.

-- Wait for a decision. If you're accepted to the academy or the prep school, you'll receive orders and a report date, and will incur a five-year, active-duty service obligation after graduation. If you're not accepted, West Point admissions counselors may give you advice on reapplying the following year or other options such as ROTC.

Related Links:

The U.S. Military Academy at West Point on Twitter

Army.mil: Inside the Army News

STAND-TO!: The U.S. Military Academy at West Point

The U.S. Military Academy at West Point on Flickr

The U.S. Military Academy at West Point

The U.S. Military Academy at West Point Admissions

Social Sharing