GARMISCH, Germany - Artillery Kaserne in Garmisch dates back to a groundbreaking ceremony Sept. 25, 1935, when it was established for what would become the mountain troops of the Wehrmacht, which the German armed forces of World War II were known as.

Since then the buildings have been extensively modified during the past 73 years, including the installation and upgrade of offices, shops and warehouses. But one feature still remains, one that frequently generates curiosity - hundreds of iron rings that dot building walls.

The rings are all waist-high and evenly spaced about the distance of a person's extended arms. Other than a lone eagle statue adorning the corner entrance of one building, the Spartan aesthetics of the original kaserne are proof that the German army of the 1930s had little interest in decorating buildings. So why the rings'

On Oct. 1, 1936, Germany's Mountain Regiment 99 and 4th Battery, Mountain Artillery Regiment 69 were transferred to the new kaserne and renamed the Gebirgs Artillery Regiment 79. In 1937 the kaserne was named Krafft von Dellmensingen, honoring the creator of the elite Deutsche Alpenkorps.

Born in 1862, General von Dellmensingen had combined snowshoe battalions together in May 1915 to form the mountain troops. A highly decorated officer, he served in World War I, commanding the 2nd Bavarian Corps during the last spring offensive and the final defensive battles of 1918. He lived to see the kaserne named for him and the battles of World War II, before passing away in 1953.

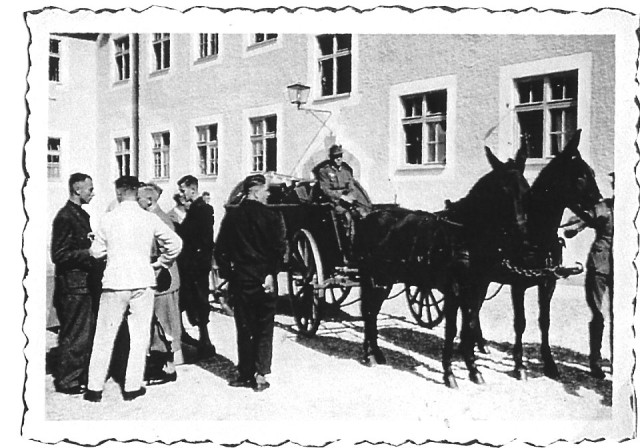

His legacy - the mountain troops - brought thousands of horses and mules with them to Garmisch. To secure these pack animals, thousands of hitching ports were built into the interior and exterior walls of buildings. A recent survey counted 454 surviving external ring ports visible on post, with only two of them missing rings. There are more rings and ports hidden by modern machinery and storage additions, and others are plastered over. Plus some are tucked away inside.

The kaserne's Building 202, with shops below and offices above, has 102 external rings, the most of any structure, despite the addition of many large bay doors and other significant modifications. The Post Exchange and commissary complex comes in second with 100 rings. One externally unmodified building in the back of the kaserne offers the best evidence of how many horses and mules could be tied outside of a single standard building with an evenly spaced 64 rings. Assuming an identical number indoors, each building could hitch about 128 animals.

The last use of the rings for their original purpose was reportedly by mounted Politzei on occasional visits to posts in the 1960s, and possibly the early 1970s.

The closest usage today is an occasional bicycle hitched to a ring instead of a rack.

Curiously, U.S. Army Garrison Garmisch headquarters, which was once a stable according to a plaque in the building, has no surviving rings.

At the outbreak of World War II, the German army was essentially still a horse or mule-drawn combat force. Hundreds of thousands of pack animals were used by Germany throughout the war, and the sure-footed mules were reliable transportation for dangerous mountain duty.

But the kaserne was never fully realized for its intended use as headquarters for the 1st Mountain Division, instead serving out the war as reserve and training center, a German army hospital and a rehabilitation station for wounded soldiers. After the war ended, it served as a hospital, prisoner of war camp and refugee housing area.

The arrival of motorized American forces in 1945 ended the pack animal era, so much so that in 1957 the kaserne became an Army facility for reclaiming and refinishing vehicles from across Europe for U.S. and NATO allies.

In 1975, 30 years after the end of the war, the German 1st Mountain Division finally moved their headquarters to Krafft von Dellmensingen, staying until 1990 before shifting south across the Loisach River to Sheridan Kaserne. Four years later they left Garmisch for Munich as part of a Bundeswehr (German armed forces) realignment.

Soon after the post became known simply as Artillery Kaserne. Today, military musicians of the Gebirgsmusikkorps of the 1st Mountain Division are the only remaining German soldiers - without a pack animal in sight.

Scenic carriage rides and a few horses in the fields south of the garrison are the only signs of what was once the primary means of military and civilian transport around Garmisch.

All that remains of their legacy are the hitching rings.

In fact, the last time horses were seen on Artillery Kaserne was for sleigh rides at the Christmas tree lighting ceremony in 2006. No word on the mules.

Social Sharing