Fort Bliss, Texas (June 25, 2012) -- From the gridiron to the battlefield, coping with behavioral health doesn't mean hiding behind a team jersey or a camouflaged uniform.

Herschel Walker -- a former NFL running back, Heisman Trophy winner and Mixed Martial Arts fighter -- faced a sea of green June 18 at Fort Bliss visiting the Warrior Transition Battalion and the Combat Aviation Brigade Dining Facility.

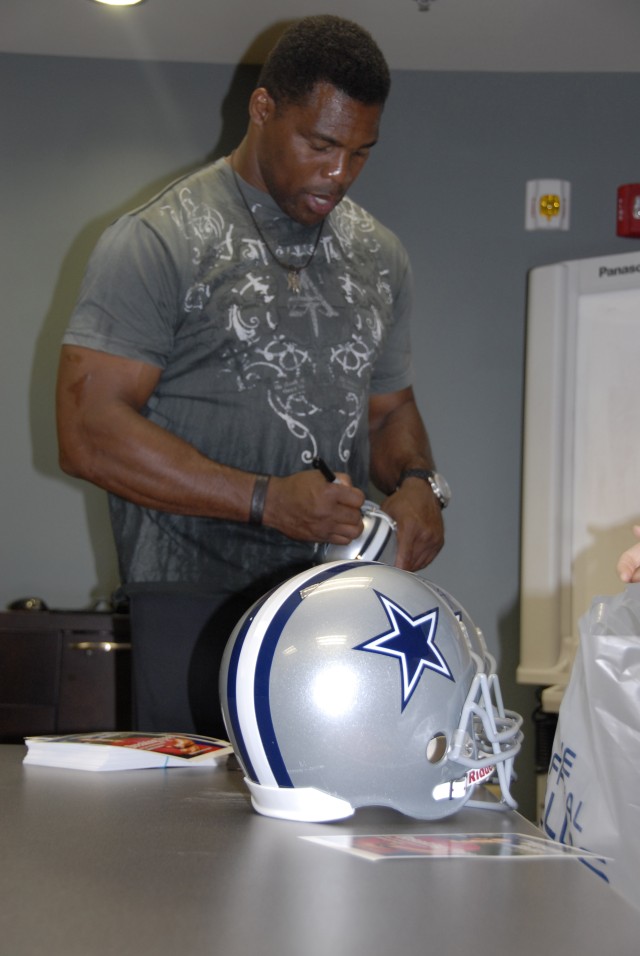

"It's different now," Herschel said as he stood in a conference room signing autographs and posing for pictures with Wounded Warriors and Cowboys fans.

"Now the face mask and helmet are off."

Shortly after retiring from the NFL, Walker was diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder -- a severe form of dissociation, a mental process, which produces a lack of connection in a person's thoughts, memories, feelings, actions, or sense of identity. For Walker it meant blacking out during episodes of intense rage.

But the world-class athlete accustomed to playing in front of thousands found his stride and coping skills in telling his story to Army Soldiers.

"What was it like to play with Tony Dorsett?" Walker responded with a grin and a few football playbacks tossing out names like Jimmy Johnson and Tom Landry.

"What's your workout routine?" A shuffling of Walker's feet and bobbing of his body accompanied a brief rundown of his intense training workouts for fights in the MMA.

"How do you cope?" Walker's face fell serious, and he replied "Every day."

Now a University of Behavioral Health spokesman, Walker says he copes every day with the issues stemming from DID.

Journaling and sharing testimonials are just a few of his coping strategies. Paired with exercise, Walker's disciplined approach keeps him focused.

"It's very important, uplifting and inspirational when famous athletes come and share their stories with Soldiers," said Chaplain (Capt.) Richard Dunbar, Fort Bliss WTB.

"You see it in the Soldiers' eyes. They light up. They grew up with or watched them on TV. Now Walker is using the same principles of discipline we see Soldiers use to stay in shape and get help."

Walker admitted he had no idea what his wife was talking about the first time she approached him about his behavior.

But Walker can remember the flash of anger that took control as he hopped in his car racing to meet a man with whom a misunderstanding evolved into an interpretation of disrespect.

Walker remembers speeding down the road, his anger building. He intended to kill the man.

Then a car in front of him slowed down, and Walker eyed a bumper sticker.

"Honk if you love Jesus."

The spiritual and born-again man was snapped back into reality. Something was wrong.

Walker said he often could not remember his episodes of anger. DID is often the effect of severe trauma during early childhood, usually extreme, repetitive physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. Walker believes childhood bullying led to his DID.

Life changed after football as Walker's once focused career had kept his "alters" on a similar course. Without the common goal, his disorder began to take control in negative and sometimes dangerous ways.

Visiting military installations around the world, Walker uses his illustrious sporting career to grab Soldiers' attention. But he uses stories of the struggles on the sidelines to relate and advocate.

"He makes it OK to not be ashamed to share your anxiety," said Donna Juarez, community liaison with UBH El Paso. "Trauma, learned behavior, health -- it's all about learning triggers and skills."

Signing his autograph to the shining surface of a Dallas Cowboys helmet, Walker carried on conversations with Soldiers and staff at the Fort Bliss WTB. Families appeared for photo ops and fans carried in bags of merchandise eager for the penmanship of an athletic hero.

"It's not always a yellow brick road to success, but people don't see the trials and tribulations," Walker said.

"Tom Landry told me once when you take something out of society (you have to) put it back in. That's what I'm doing. There's no shame in getting help."

Social Sharing