FORT LEONARD WOOD, Mo. -- The world of a drill sergeant is multi-faceted and always changing. Every Basic Combat Training cycle, they're faced with new challenges, new civilians to shape into successful warriors -- and each drill sergeant has their own way of doing that.

A BCT cycle is divided into three phases: Red, White and Blue.

According to many drill sergeants, toughest part is always Red Phase, or the first three weeks of training.

Sgt. 1st Class James Metts, Company A, 795th Military Police Battalion, 14th MP Brigade, described Day 1 as "a lot of yelling, and pretty much, they do nothing right."

During Red Phase, trainees get introduced to military life and Army Values. Training includes drill and ceremonies, first aid, communications, combatives, land navigation, and chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear training.

This is the time when drill sergeants are most involved with the trainees -- from dawn until dusk.

"The first three weeks … is 'total control,'" said Staff Sgt. Alan Forester, a drill sergeant with Company C, 31st Engineer Battalion, 1st Engineer Brigade.

"You actually have to integrate them and actually get them to understand discipline and the Army Values. So, you have to have a complete presence at that time --at least one drill sergeant around at all times, and this is a seven-day-a-week job," he said.

In general, drill sergeants work 16 to 17 hours per day, six days a week, and even longer during Red Phase, Forester said. A typical day starts around 4:30 a.m. and ends between 7:30 and 8 p.m., he said.

"In Red Phase, we don't leave until 2100," he added. However, "The hours start getting less and less as it goes along."

During those first few weeks, drill sergeants inspect their Soldiers on every detail, from the way they shave and make their bed to the way they respond to commands.

"It's like teaching a newborn how to do something," said Staff Sgt. Russell Cash, Company A, 3rd Battalion, 10th Infantry Regiment. "Part of your job is to break down everything so everyone can understand it."

The Soldiers also learn -- quickly -- to respect authority and follow directions.

"The first three weeks, you can tell who's going to make it," Cash said.

During White Phase, Soldiers begin to work on marksmanship and tactical skills. There is an emphasis on self-discipline and less drill sergeant control.

"(In) White Phase, you sort of get … a little more relaxed, but not to the extent that they lose their discipline. You come into a kind of more of a mentorship role, to try to teach them to how to fire a weapon -- a lot of them are scared to fire a weapon," Forester said.

"If we're constantly telling them what to do on the practical exercise, we're not really helping them. We kind of … stand back and allow them to perform," he said.

In Blue Phase, the final weeks of training, trainees are encouraged to show troop leadership. This phase includes field exercises and culminates in graduation.

Once a class graduates, drill sergeants have anywhere from a few days to a few weeks to get ready for the next cycle.

The long hours can be hard, but seeing the results of those hours make it worth the effort, Forester said.

"The long hours pay off," Forester said. "If you see what you've done … what your Soldiers have accomplished, the long hours pay off."

TO YELL OR NOT TO YELL

Each drill sergeant has their own way of coaching civilians into Soldiers.

"Through the initial phase and through integrated and reception, of course we're going to be yelling a little bit more," Forester said. "We have to yell so everybody will be able to hear us and to get everybody's attention."

However, during the bulk of Basic Combat Training, drill sergeants don't yell "as often as you might think," he added.

"We are trying to turn civilians into Soldiers. Just yelling at them isn't really teaching them anything," he said. "When we're in a classroom environment, I let them relax a little bit, just so they will understand what I'm teaching them, because you can't really teach anybody in a stressful environment. However, when we're doing our practical exercises, I like to put a little bit more stress on them, to see how they can react under stress. It depends on the environment we're in."

Cash tries to make himself more approachable.

"Every NCO has a different way of doing it," Cash said. "I'm not a real big yeller. I yell if I have to, but I'm not the one that's going to be sitting there yelling at you every single day to make you do stuff. I just basically talk to them."

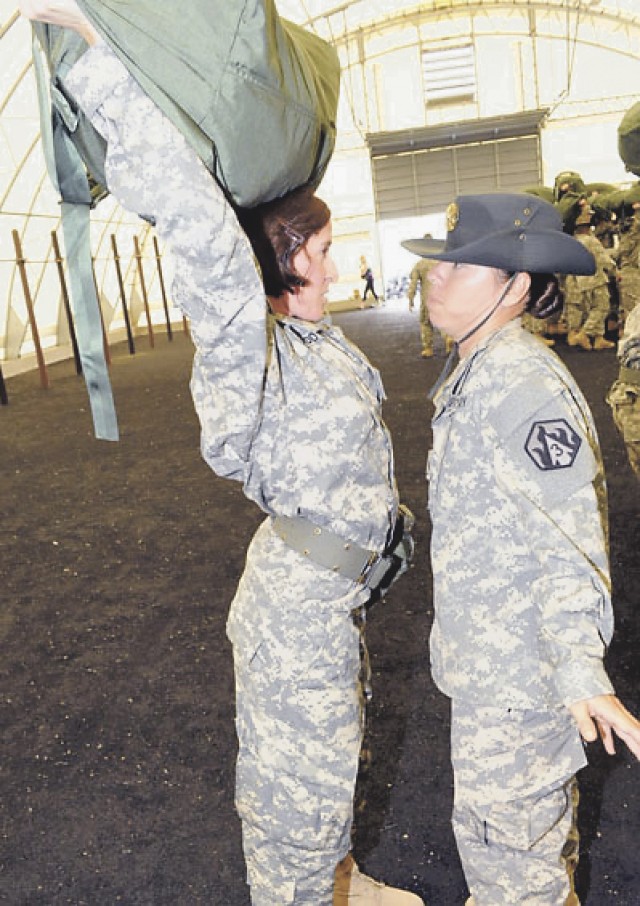

Staff Sgt. Blasa Ortiz, a female drill sergeant for Company E, 2nd Battalion, 10th Infantry Regiment, tells it like it is.

"I'm a yeller," Ortiz said. "I will yell at you from Day 1 until the day you graduate."

However, her biggest weapon for whipping Soldiers into shape isn't a loud voice.

"The best way, I've learned, is when you tell them you're disappointed. That's what crushes them," she said. "They want to please you, and they want to make you happy."

If a private misbehaves or is late to physical training, everyone else pays the price.

"I tell them every day, the choices you make don't affect you, they affect everybody else," she said.

"At the end, a lot of privates, whether they were in my platoon or not … they'll thank me," she added.

Ortiz was named Drill Sergeant of the Cycle a few months ago. She counts being a drill sergeant as the biggest accomplishment of her military career.

"It's where you impact the most lives," she said. "This is the way you can change the Army."

(Editor's Note: This is the second installment of a two-part series on what it takes to be a drill sergeant.)

Social Sharing