PICATINNY ARSENAL, N.J. (May 16, 2012) -- As far as the design of the basic hand grenade goes, essentially it has been frozen in time.

The first pull-pin design with a lever and delayed fuze dates back to May 1915 and is often referred to as the grandfather to the current variation.

"The basic technology is almost 100 years old," said Richard Lauch, a Picatinny Arsenal engineer, referring to the Mills Bomb No. 5.

The Mills bomb is the popular name for a series of prominent British hand grenades. They were the first modern fragmentation grenades and named after William Mills, a hand grenade designer.

Lauch, who served in the U.S. Marine Corps, has been on a mission to modernize the hand grenade so that it is safer as well as easier to use and cheaper to produce.

During the last year and half of his Marine service, Lauch was primary marksmanship instructor in the Weapons Training Battalion at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, Calif.

While he was assisting in training recruits on the proper use of the M67 hand grenade, Lauch became intimately familiar with what he saw as the grenade's deficiencies.

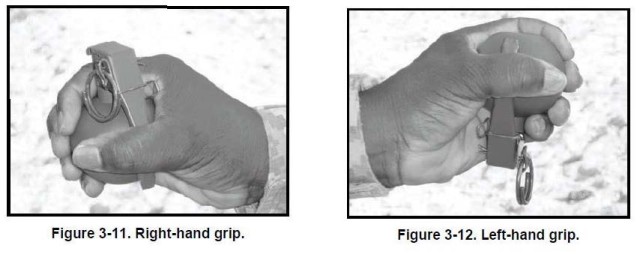

The current grenade fuze design only allows for a right-handed user to throw it in the upright position. A lefty has to hold the grenade upside down to safely pull the pin.

Also, the current fuze consists of an explosive train that is in-line from production through usage; thus, it is always "armed."

In a grenade, the explosive train is the sequence of events that begins when the handle is released. That initiates a mechanical strike on a primer, which ignites a slow-burning fuze to provide time for the grenade to be thrown before the fuze sets off the primary explosive.

In an "in-line" explosive train, the sequence is always in-place and ready. Until it is removed, a pin in the handle is the only thing that prevents the sequence from being initiated.

Lauch believes his design is safer because a lefty or righty holds the grenade no differently, and because the grenade can only be armed by rotating the explosive chain in line.

CHAIN OF INVENTION

Lauch came to the Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center, known as ARDEC, in 2008 after working several years in private industry.

About a year and a half later, his idea came to Lauch after he read about an injury to a Soldier who was training at Fort Dix, N.J. A year and a half after, he submitted a patent application for his project.

The Soldier at Fort Dix, a lefty, was preparing to throw an M69 practice grenade and was holding it in an inverted position with the vent port toward her face. Even though the master sergeant was wearing protective eyewear, when she pulled the pin, the fuze detonated and debris vented, burning her face and blinding her for three weeks.

"What struck me most was that a Soldier, miles from home for what was supposed to be temporary training, was now sitting in her barracks room blinded," Lauch said.

During Lauch's research, he noticed that for hand-emplaced devices, the fuze safety policy for a new fuze design requires an out-of-line explosive train until it is ready to be armed.

"When I started exploring a means to make the grenade ambidextrous, it led itself to an out-of-line design. There was no way around it with what I was doing," Lauch said. "Something was going to have to rotate. It was just one of the things that happened to fall into place with what we are striving to do."

Lauch's patent application design includes a safety that requires two distinct actions to arm the grenade.

The first motion ensures that users have a firm grip and control of the lever before they can arm it.

The second motion "arms" the grenade by rotating the explosive train in-line. If the tactical situation were to change, the Soldier just reverses the second step and the grenade is re-safed. Currently, re-safing a grenade requires trying to reinsert the sometimes-deformed safety pin, which is not easily done.

Another reason Lauch was determined to make an improvement was that Soldiers have been known to make their own modifications to grenades when they know there is potential for an accident.

"I know that if anyone ever got on my chopper with a grenade, the crew ensured they all taped the pins in with duct tape so there was no room for an accident," Lauch said.

However, when the tape is removed it may unintentionally remove the safety pin, resulting in serious injury or even death. In recent years the Army disallowed the taping of grenade pins and started a training campaign to reinforce safe practices.

"If we send a finished product to the field and the warfighter has to modify or alter it for their mission, then we didn't do our jobs very well," he said.

"It's been going on for decades, from aircrewmen using a C-Ration can to aid the belt feed on the door-mounted M60s to this," Lauch added. "Instead of telling a warfighter, 'Don't do that,' we need to make it so they don't want to make any modifications."

After bouncing his idea around the office, Lauch became frustrated that there simply was no funding for his concept because there was no written requirement for a new grenade design.

With troops in combat, the Army places a premium on delivering capabilities based on what combat troops say are their most pressing needs. The Army has a detailed process to document these needs into written requirements.

Lauch believes that the reason there is no real requirement is because the Soldiers are unaware that a better version could exist.

"If you asked someone in the 1880s how you could improve a horse and carriage, they would tell you they would want it to go faster. They had no idea that the automobile was next in line," Lauch said.

He became determined to prove that he was at the cusp of something great. Lauch worked daily during his personal time to bring his idea to reality.

Lauch then turned to the Innovation Developments Everyday at Army Research, or IDEA, Development and Engineering Center also known as ARDEC, or IDEA program and one of the program's "catalysts," Andrea Stevens.

An idea catalyst encourages and fosters ideas, helping to refine existing ideas, to connect associates with other ARDEC entities, and advise associates on the innovation processes.

With some guidance and working with Stevens, paperwork was submitted for more funding and to acquire a patent for the new grenade design concept.

"This is a great example of the advantage of having an innovation process and catalysts there to assist these engineers," said Maria Allende, a Grenades and Mortars Fuzing Team Leader.

Lauch received some funding from the office of John Hedderich, executive director of ARDEC's Munitions Engineering Technology Center. Lauch presented his idea before the patent evaluation committee with just two days notice. The committee liked what it saw and labeled it a high priority.

On Dec. 29, 2011, a patent application was filed.

"We could have put him on any program," Edwina Chesky, a Fuzing Systems branch chief, said of Lauch when he first arrived at Picatinny. "Luckily we put him on grenade fuzes."

Lauch and Philip Gorman, the competency manager for Fuze Division, agree that there is still a lot of work on the product that needs to be explored. Final dimensions and delay mechanisms are still to be finalized. A patent does not mean a product will end up in the hands of troops anytime soon.

SOLDIERS NEED PERSUADING

"There is still no documented requirement from the field and there has been a resistance from the user to accept a radical departure from the old design," Gorman said.

Lauch acknowledges that it takes a lot of persuading to gain acceptance from Soldiers.

"But at the same time, it is their opinions that you want because they will find any and every flaw you haven't thought of and if they can't find any you know you have a good design," Lauch said.

Currently, there are only 12 prototypes in inventory and further research is still needed. But Gorman and Lauch believe there are further benefits besides improved operational safety.

"In the production of the M67 hand grenade, inspections are conducted to ensure that none of 20 potential critical defects related to the in-line assembly of the explosive train are present" Gorman said.

He said that with the improved safety features, fewer inspections need to be implemented, creating potential cost-savings.

Reducing the number of critical defects to be inspected reduces the amount of time spent on inspections and testing.

"At the end of the day, grenade fuzes are a real bear to make," Gorman said. "Driven by the fact that you screw it in-line. This explores the possibility to get rid of that in-line explosive," he said.

For the approval of his patent application, ARDEC will receive a $200 invention award. Lauch plans to donate the prize money to the Wounded Warrior Project to help other injured Soldiers like the injured master sergeant at Fort Dix that inspired Lauch to pursue his goal of putting a new grenade out in the field.

Social Sharing