When captains arrive at the Special Forces Qualification Course, their primary instructors are NCOs who have been on small Special Forces teams downrange.

These NCOs take their skills, expertise and knowledge, and instruct their future leaders on what each member of a Special Forces team is capable of. After graduation, SFQC students will join an operational detachment A (or Special Forces A team) downrange.

Master Sgt. Shawn Thompson, an 18F special forces intelligence sergeant, served on a team for three years before coming to the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg, N.C., as an instructor for the SFQC's military occupational specialty phase for 18A detachment officers.

"The inside joke is we're training captains who are supposed to be smarter than us," Thompson said. "But [their knowledge is all] book knowledge, and we show them how to apply that book knowledge the way it needs to be applied. That's the strength of the NCO."

The NCOs who train the captains at this course bring a different perspective -- how teams operate and what each team member brings to the table, Thompson said. An ODA is made up of a 12-man team: a detachment commander, an assistant detachment commander, a team sergeant, a special forces intelligence sergeant, two weapons sergeants, two engineer sergeants, two communications sergeants and two medical sergeants.

Knowing who is responsible for what and how NCOs work together is critical, Thompson said. That information is what NCOs pass along to captains during the 14-week MOS portion of the course.

"We've had so much team time, held different positions on teams and have watched a lot of captains," Thompson said. "Captains only get a couple years on a team; an NCO can get 13 years on a team. You see a lot of captains come through, you see how they interact, you know what a team is responsible for. And what each section on the team does, you have that expertise yourself. By bringing that to the table, you're able to bring to the captains how a team operates and, basically, allow him to find his place on a team."

Master Sgt. Steve Everett has served 14 months at the Special Warfare Center as an instructor and served two years in Okinawa, Japan, as a team leader.

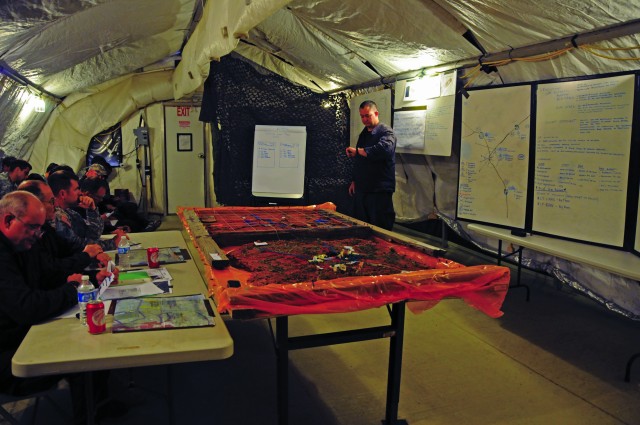

He said NCOs bring their downrange experience to captains in the classroom so that those captains can see directly how textbook theories and tactics are applied on the battlefield.

"We have to make sure that they understand what's being taught, not just on a book basis, but on an operational basis," Everett said. "NCOs have been in the environment, and we know what works in that kind of small Special Forces team."

NCOs help expose officers to the realities their Soldiers will face and the things the officers will have to keep in mind when they're downrange, Everett said.

"[A captain] needs to be able to consult the senior noncommissioned officer and the rest of the men on his team," Everett said. "Officers are oriented toward planning; NCOs are more directed toward taking care of their men."

During the course, NCO instructors act primarily as observers. They assist and guide officers through the training, and can be used as a resource. They also lead after-action reviews once the training missions are complete.

Steve McDaniel, a retired sergeant major, served 18 years on a Special Forces team, 16 of which were spent downrange. He currently serves as a contractor with the SFQC, where he provides information to the command about students in the course and guides students through role playing, which is based on doctrine and his experience.

"It says a lot about NCOs that are [teaching here]," he said. "It says a lot about the command that NCOs are enabled to teach these officers everything they need to know so they can be successful commanders.

"A lot of time, you don't get that NCO point of view," McDaniel continued. "All of these NCOs have served on a team as an NCO team leader. They know the weaknesses that they've seen in the past, as well as the strengths. They're the only ones here with team experience. An officer can't share what the Soldiers on the team feel like; they can command a lot better if they know what the guys on the team are experiencing."

Sgt. Maj. Gil Vargas, who oversees the instructors during the MOS-training portion of SFQC, said that being an instructor can help an NCO's career. An instructor at the school has the best promotion potential to become a staff sergeant or sergeant first class within the special operations community, he said.

"It expands an NCO's horizon and prepares him for the next level of responsibility by executing his duties here," Vargas said. "It's a very challenging job as an NCO because now you have guys who are really, really smart. The NCOs have to stay one step in front of them all the time"

The NCOs also have to demonstrate their professionalism, qualification and experience daily, Vargas said.

"If you look at what the definition of a 'professional' is, my view is it's a guy who's in shape, who's very smart, thinks outside the box, is committed to his mission and has passion for what he does," Vargas said. "Those are the guys I have working here as far as NCOs."

Social Sharing