FORT LEE, Va. (March 1, 2012) -- In Iraq, the enemies of coalition forces had a crafty way of communicating threats to anyone they wanted to erase.

"Their way of threatening is the traditional way," said Pvt. Adel Alogaidi. "They delivered a letter and put a bullet within the letter and basically said that I am a traitor; that I am helping the infidels and if I didn't quit my job, this bullet will be inside my body or the body of one of my family members."

It was 2007, a time of escalating violence during Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Alogaidi, a native translator, had been found out.

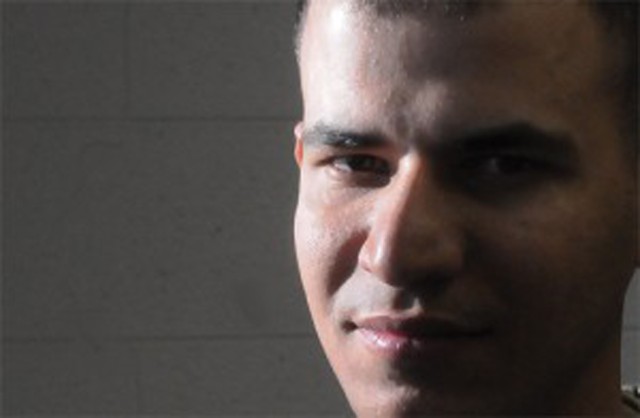

"Somehow my name got out or somebody recognized me or something, so I got threatened and had to leave the country," said Alogaidi, now an advanced individual training student assigned to Romeo Company, 262nd Quartermaster Battalion, 23rd QM Brigade.

Iraqi translators working for the U.S. government took on the same risks as the Soldiers they supported. In addition, their family members and friends were targeted, and many translators lost loved ones in retaliation. It seemed the word "traitor" was synonymous with "translator," and that meant collaborating with the enemy and living under the threat of death to perform such a job, regardless of the motive.

"Most Iraqis viewed the American Army as invaders, not as a people who helped them to get rid of a tyrant and re-established their country," said the 28-year-old Alogaidi. "That's clearly explainable. Most of the people have poor education. They are very simple people, and they cannot comprehend the idea that those forces are helping, so if you are working with those forces, you are helping the invaders."

Alogaidi began his translator work in 2007 with the U.S. Army's National Police Transition Team. It was in charge of training and rehabilitating the Iraqi national police. Alogaidi said his job involved much travel, and that posed an abundance of hazards.

"For the most part, it was dangerous," he recalled. "The danger of it was the IEDs all the time. We were always afraid we were going to be hit, and we were because we travelled in long convoys. Luckily for me but unfortunate for others, we would just miss it or were too early for it."

On top of the threats and physical dangers of the job, Alogaidi had to battle his own loyalties and emotions.

"When I first worked with the U.S. Army, I felt guilty," said the Baghdad native, noting he was torn. "You cannot help being affected by your culture. But when I began working with the Army, I didn't see anyone kill anyone. I didn't see the U.S. Army abuse locals. I didn't see any of that.

"I saw a group of people who were trying their best to complete their mission and go back to their country."

Alogaidi said the Americans' noble efforts to rebuild the country inspired him.

"Day by day, I began to love that job," he said, "and I believed in what they were doing. Many times I got the opportunity to leave my job, but I chose to stay because it was more than a job. It was doing a job and saving Iraqi people."

As the country became more stable, Alogaidi began to make more trips home.

"In 2007, I wasn't going home much," he said. "In 2008, I kind of became comfortable with the idea that I'm working for the U.S. Army and began to go see my family and some of my friends."

Alogaidi's comfort and freedom would end there. Like many other translators, he was forced to flee, leaving family, friends and all that was familiar to him. Alogaidi entered the states in 2009 under a special visa program set up for Iraqis who worked for the U.S. government. Retired Air Force Lt. Col. Peter Glawe sponsored and mentored him.

"Adel Alogaidi is a very unique young man," said the Vietnam veteran and San Antonio resident. "He has adapted to his new life in the U.S. very well, made many friends, worked in the civilian economy prior to his enlistment and has become fluent in English. He is extremely motivated to succeed, despite the fact that he may never see his family again."

Glawe and other friends encouraged Alogaidi to join the entity he had been working with all along.

"They told me you are not probably OK with the idea of being a part of a foreign military, but the more you are in the U.S. Army, you will actually find people from all over the world," he recalled. "They said it is all about diversity."

The notion of diversity exceeded Alogaidi's expectation when he shipped out for basic training in September 2011.

"When I came here (joined the Army), I met people from countries with names I don't know," he said.

While Alogaidi marveled at the good that he found in the U.S. Army, his Iraqi homeland was still in turmoil. Roadside bombs and IEDs were still a problem. In September 2011, shortly after he enlisted, his mother became a casualty of a car bomb, one of the hazards he had escaped many times before.

"My mother is recovering, and I hired a nurse who can take care of her," said Alogaidi. "My mother herself told me to stay there (in the United States). She said, 'I need a female to take care of me, not a male.' I decided to stay."

Alogaidi said the Army has given him a few good reasons to remain. He gained his citizenship while in AIT, learned as much about America in the process of becoming a Soldier as he did anywhere else and has gained a newfound comfort in his new home.

"Don't get me wrong, I love Iraq," he said, "but I don't feel like I'm Iraqi here, and I don't feel like the next Soldier is American. I just feel like a Soldier, part of a group. I don't feel like the black sheep, the one who is different."

Alogaidi is scheduled to graduate March 8.

Social Sharing