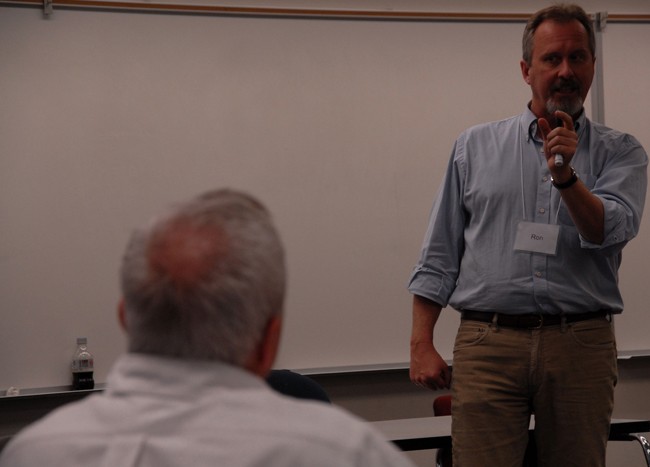

WASHINGTON (Feb. 18, 2012) -- "You can tell the extroverted writers; they are the ones that stare at your shoes while they are talking to you, while the introverted writers stare at their own shoes," Ron Capps, founder of and instructor with the Veterans Writing Project, joked during a weekend seminar.

The borrowed classroom on the George Washington University campus in Washington, D.C., was filled with both varieties of writers. The lunch hour consisted of quiet discussions among men and women of all ages--some staring at their shoes, others staring at someone else's -- all discussing their experiences in the military with each other.

"The basic idea behind the project is working writers, who are graduates of Master of Arts or Fine Arts programs and veterans -- you have to meet all three of those criteria -- come and give away what we know to others," Capps said, about the VWP. "Veterans, family members, active and reserve servicemembers, anybody who wants to write about the military experience" are welcome to join the seminar.

A Soldier for 25 years, Capps completed two tours in Afghanistan, and was later sent to Iraq as a Foreign Service officer (he has also served in Rwanda, Darfur and Kosovo). He was traumatized by the violence he encountered. Therapy and prescription medications meant to help him deal with his memories did nothing.

"(I) came very close to committing suicide -- I was actually interrupted. I survived, obviously, and now I'm here. Writing helped me get control of my mind."

Capps is a regular Time Magazine contributor, and has been a featured speaker on NPR's "All Things Considered." In 2008, he left government service and attended the graduate fiction and nonfiction writing programs at Johns Hopkins University, where he got the idea to start the project.

One night, while driving home from class, Capps began to consider what he would do with the knowledge he was acquiring.

"I'm learning a lot, I'm a working writer, I'm in graduate school … what can I do with it? And I thought, writing helped me, maybe it can help others," Capps explained. "And so, about a year ago, the idea came to me to start the Veterans Writing Project, and we incorporated in January of 2011 and started teaching seminars."

The VWP, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, has several goals in mind -- primarily, to help people involved with the military tell their stories by providing tools and advice to build a foundation for good writing.

Larry Rock spent three years in the Marine Corps, including a tour in Vietnam from August 1965 to September 1966. He was a clerk and driver with the 1st Marine Air Wing, and spent most of his time supporting combat troops. He came to the seminar to get some feedback on his book, learn about the publishing process and share a story that he said hasn't been told before.

"I am putting together an oral history on (the support troops') role," Rock said. "In World War II, the ratio of support troops to combat troops was four to one; in Vietnam it had risen to 10 to one. Ninety percent of those sent to Vietnam were not sent to fight."

Rock took a year to interview 150 support troop veterans for his book, which has the working title of "The Tooth and the Tail." He is working to find a publisher, and hopes the book will provide a better understanding of what went on in Vietnam.

"I think there are a lot of stories to be told," Rock said, explaining that the difference in some common war stories lies simply in the experience of the individual and how it affected them. "It's different for everybody, but there's also things to be learned from it."

Another project goal, according to Capps, is to bridge the social and communicative divide between the minority of the population who serve in the military and civilians. He said that writing could also provide a therapeutic release for some participants.

"We want to help people tell these stories, and if there's a therapeutic aspect (like) the way it worked for me, so much the better."

Controlling the experience

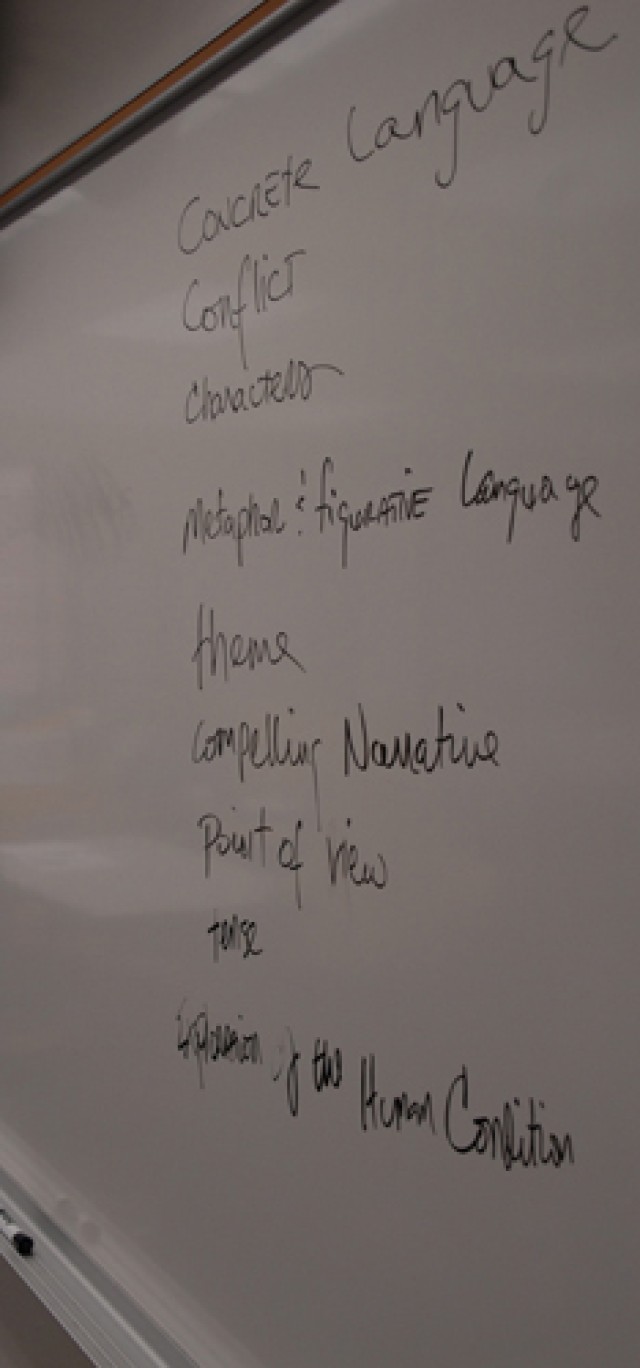

The fall 2011 VWP Open Seminar was held the first weekend in November. The project curriculum follows Capps' book, "Writing War: A Guide to Telling Your Own Story," and can be taught as a traditional semester-long workshop class, or as an intensive two-day seminar. In the seminar, participants run through the entire book and share short writing exercises, but don't critique others' works.

George Washington University's Veteran's Service Office and the university's writing program sponsored the seminar, which is free for participants.

"We start with the questions, 'Why do we write?' Why do we bother?' And then, 'What's different about writing the military experience?'" Capps said.

Writing about an experience as a servicemember can be daunting, not just because the individual may have the need to relive traumatic events, but because now those events are being shared with the world at large.

"The saying is, 'Either own your story or it owns you,'" Dario DiBattista, another project instructor, said. He explained that by sharing and reliving traumatic events, a person is taking charge of what happened and acknowledging that he has moved on.

DiBattista served six years in the Marine Corps Reserve and completed two tours in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He started blogging after his second tour as a form of self-help. Now, DiBattista has finished two books -- a memoir and a novel -- and has literary nonfiction and poems forthcoming in publications like The Washingtonian and The New York Times.

"Writing was quintessential to me to help get over my issues resulting from my experiences overseas," he said. "And because I had that, I was able to overcome it. I want to teach people to be able to do the same thing. I want to show them the story I learned, the techniques I learned."

The military is less than one percent of the population, DiBattista explained. He believes that it is important for servicemen and women to share their stories and advocate for that population through spreading awareness and attention to the experiences of war.

"What happened to me, my experience, I think that I needed to write about it to get control of it, to control those memories," Capps added. "But I also, whether it's true or not, actually believe that I have some kind of commentary on the human condition. What I experienced can explain the human cost, the individual human cost of the wars that I went through, and I think that's worthwhile."

Captain Steve Scuba, an Army nurse, has worked at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for six years. During his tour as a combat nurse in Iraq, Scuba sustained shrapnel wounds. His experience is unique in that he saw the war from both sides of the hospital bed.

"I went to Iraq during the surge in the fall of 2007, and all of 2008, I served with the 86th Combat Support Hospital, the 86 CASH," Scuba explained. "I served five months in Mosul in northern Iraq, and then 10 months in Baghdad."

Scuba works at the hospital's Warrior Transition Brigade, which helps injured Soldiers transition back into the Army, or to civilian life.

"At Walter Reed, we started a writing program for wounded warriors about a year and a half ago," Scuba explained. "We meet once a week and most of the things we write about are similar to this, the experiences that we had in the military, whether it's in the war zone or just what it's like being in the military."

Scuba participated in the seminar to not only learn some of the tricks of the trade to help shepherd his own war memoir on it's way, but also to bring back information on the VWP to his wounded warriors at the WTB. He believes that just like men and women from previous conflicts, current veterans have the mentality that they shouldn't talk about their war experiences. Writing is a way to get around that mental block.

"It's a grand thing to do. It allows people to know what went on -- there's a historical aspect to it. There's also a therapeutic component, whether it's realized or not, but I think by doing that you can make some sense of the stuff that went on, both good and bad," Scuba said.

Believe in your story

Teaching someone to be able to write well isn't something that happens overnight, or even over the course of a weekend, Capps and DiBattista agreed, but it is possible to teach participants the basics.

"(Our goal) really is to give our participants the tools they need to be a writer, whether that's poetry, fiction, non-fiction," Capps said. "I'm not going to train someone over a weekend to be a competent, functional, professional writer. We're going to give them the tools that, with practice, (will help them) become writers."

Throughout the course, instructors stress that writing -- whether it's done to overcome the effects of a traumatic event or because it's been a lifelong love -- is hard work. They emphasize the need for continual practice and, above all else, to believe in what you have to say.

"Take the chance, live large," Capps said. "Hemingway drove an ambulance in the first World War, (and) later won the Nobel Prize for literature. Faulkner was an aviation cadet -- he never got into combat because he crashed his airplane; he's also a prodigious liar. But he's a veteran, and later won the Nobel Prize for literature. This is possible."

DiBattista explained that he isn't trying to make people uncomfortable with his writing. For him, it is simple: Writing is a way for him to face his demons and move on.

"I believe in my story," he said. "I've read all the Iraq and Afghanistan war literature there is. I don't think anybody's nailed it yet. I believe in what I'm doing and it's important for me to get my story out there."

For more information about the VWP and upcoming seminars, visit www.veteranswriting.org.

Social Sharing