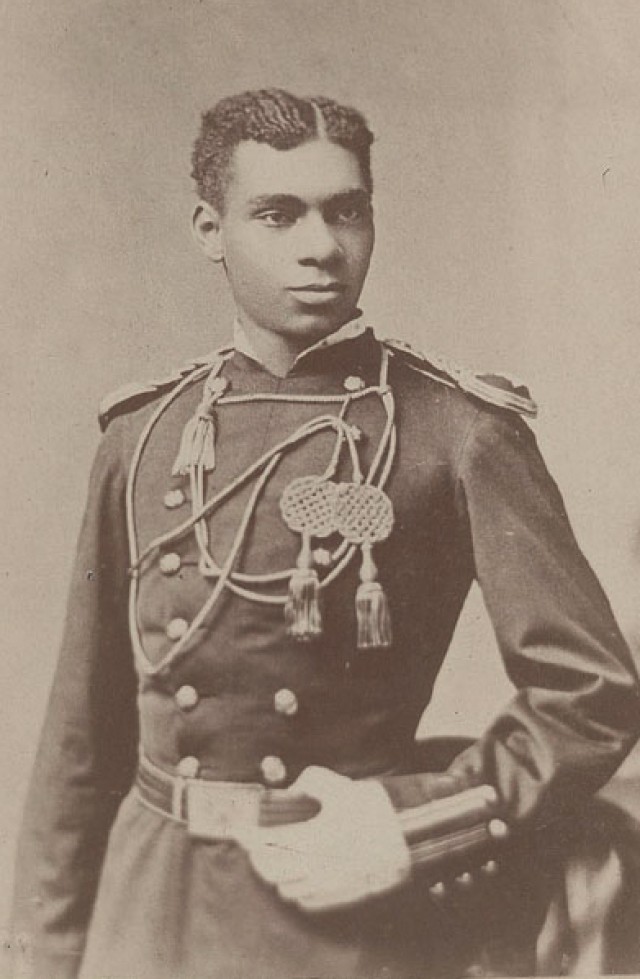

FORT SILL, Okla.-- Henry Flipper graduated as the first black officer from the U.S. Military Academy in 1877. As a second lieutenant, he influenced the history of the Army, and America, as much as anyone else.

Flipper was born into slavery in 1856 in Thomasville, Ga. He was taught to read when he was 8 by an educated slave. After the Civil War, Flipper's family moved to Atlanta where he attended a missionary school, and then studied at Atlanta University. But his true desire was to serve in the Army and attend West Point.

Blacks had fought with distinction in the Civil War and afterward the Army wanted to train black officers to lead all-black Army units. But the academy vigorously fought admission of black cadets. A white Republican congressman from Georgia appointed Flipper to West Point in 1873.

Flipper was the fifth black candidate to apply to the academy and the third to be accepted. White cadets avoided talking to him. Flipper endured four years of persecution and isolation in the face of harsh racism. In spite of hostilities from cadets, the officers and instructors encouraged him to stay when he often wanted to quit.

In 1877 Flipper was commissioned as a second lieutenant, becoming the first black commissioned officer in the Army and was assigned to the 10th Cavalry, the famed Buffalo Soldiers.

The 10th Cavalry had been formed only 10 years earlier at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. under the command of Col. Benjamin Grierson and his adjutant Capt. Nicholas Nolan. Nolan commanded Troop A, and served with the Buffalo Soldiers for the next 15 years.

When Gen. Philip Sheridan established Fort Sill in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in 1869, Grierson became the post's first commander and brought Nolan and the Buffalo Soldiers to help construct the new fort.

The Buffalo Soldier regiments rode with other units from Fort Sill to protect wagon trains and cattle herds that traveled along the nearby Chisholm Trail in Indian Territory and north Texas. In early 1878 Flipper was posted to Fort Sill as the first black commander of Troop A, 10th Cavalry, under commander Nolan. Prior to Flipper taking command, all-black units were led by white officers.

At Fort Sill, Flipper applied the engineering training he received at West Point. The area where troops set up camps became swampy after it rained and a breeding ground for mosquitoes that carried malaria. Flipper designed an effective drainage system that eliminated the stagnant water and the malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Still known as "Flipper's Ditch," it became a national landmark in 1977. Flipper also surveyed the post and led the Buffalo Soldiers to build new roads and telegraph lines.

The young black officer became close friends with commander Nolan, who began training Flipper to be a good cavalry officer. He invited Flipper to dinner in his quarters on several occasions, which caused other white officers to try and censure Nolan. But Fort Sill commander Grierson dismissed the accusations, because he knew the basis of this discrimination. Nolan defended his actions by stating that Flipper was an "officer and a gentleman, just like any other officer at Fort Sill."

Flipper would usually decline invitations to social events on post, choosing to spend much of his leisure time riding with Nolan's sister-in-law, Mollie Dwyer. Flipper received high marks from his commanders but was the subject of jealous rumors and letters that hinted of impropriety between Flipper, a black man, and Dwyer, a white woman. This began a smear campaign against Flipper that would later cost him dearly.

In 1881 Flipper and the Buffalo Soldiers were transferred to Fort Davis, Texas and soon fell under the command of Col. William Shafter. Shafter disliked blacks in general and the Buffalo Soldiers in particular. Shortly after the colonel's arrival, Flipper was accused of stealing commissary funds. Flipper stated at his court martial, to keep the money safe from thieves, he hid the funds in his personal trunk. He did this because there was no secure place to keep the commissary funds and that Shafter was fully aware of this. Despite the fact that Shafter found $2,800 in commissary checks in the possession of Flipper's white housekeeper and cook, this fact was never mentioned at the trial. The local town merchants, who highly admired Flipper, took up a collection and replaced all the missing funds. The nine-man court martial panel (that included three of Schafter's officers) could not convict Flipper of embezzlement, but were able to convict him of "conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman," based solely on personal letters from Dwyer that were taken from Flipper's quarters when they were searched. Although the Army's judge advocate general concluded that the conviction was racially motivated, President Chester Arthur refused to reverse his conviction, and Flipper was dishonorably discharged from the Army June 30, 1882.

Disgraced, Flipper sold his horses and went to El Paso, Texas. There, he used his West Point education to establish a distinguished career as a civil and mining engineer along the Mexican border. He had become fluent in Spanish and translated many court documents and land appraisals. He also wrote many books and articles that were widely recognized. Flipper would rise to prominent positions of leadership with the U.S. Justice Department and Senate foreign relations committee as an expert on Mexican political relations. Later, he became the assistant secretary of the Interior, where he was chief engineer for the planning and construction of the Alaska Railway system.

From the moment he was dismissed from the Army, Flipper fought to clear his name and have the charges reversed. He tried to return to the Army during the Spanish-American War and again during World War I. Both times his application for reinstatement was denied. Only when his health declined did he give up his fight to clear his name. He moved back to Atlanta and lived with his brother until his death in 1940. Flipper never married.

But the campaign to clear his name did not die with his passing. Several individuals renewed the effort in the 1970s and on Dec.13, 1976, the Army granted a full pardon to Flipper after an extensive review of his record, and of the testimonies and proceedings of the court-martial. And, in 1999 President Bill Clinton pardoned Flipper posthumously, thus restoring his rank and the achievements of his military career.

Today the Henry O. Flipper Memorial award is given to the most outstanding cadet at West Point who best demonstrates leadership, self discipline, and perseverance.

Despite Flipper being the first black academy graduate in the Army, it remained difficult for other black cadets to make it through West Point. Between 1870 and 1889 only 22 blacks received appointments to the academy. Twelve applicants were admitted but only three graduated despite four years of discrimination and social isolation. In addition to Flipper, only two other black cadets would graduate in the 19th centuryJohn Alexander, in 1887 and Charles Young, in 1889. A fourth black wouldn't graduate from West Point for another 46 years.

The passing of time has changed America, and the Army. The legacy of Henry Flipper lives on in the careers of distinguished black Soldiers and officers who have served their country despite difficult obstacles. Today, there are more than 300 black cadets at West Point, preparing to be the officers and leaders of the future Army.

Social Sharing