FORT SILL, Okla. -- You may have noticed that Fort Sill has an airfield.

And it's not just an ordinary airfield. It is the oldest continuously operating Army airfield, almost 100 years old, and is considered the birthplace of Army combat aviation. It was established in 1917 as the Henry Post Army Airfield, and was named after Henry Post, one of the earliest aviation pioneers. Post established a new altitude record of 12,120 feet at San Diego, in 1914. Sadly, he was killed when the wing of his plane collapsed as he came in for a landing.

Aviation activity at Fort Sill actually began in 1915, two years before the airfield was established, when the 1st Aero Squadron was created under the command of then Capt. Benjamin Foulois.

"The squadron was made up of Curtis JN-3 'Jenny' biplanes that were shipped here in crates. They didn't fly them here. They unpacked the crates right out here on the Fort Sill Post Quadrangle parade grounds," said Towana Spivey, retired curator and director of the Fort Sill National Historic Landmark Museum. "After they were assembled they walked them down the hill and flew them for the first time, right off the Fort Sill polo field. There was no airfield at that time."

"The 1st Aero Squadron pilots were all taught to fly by the Wright brothers, but they didn't have any training in navigation," Spivey said. "There were no radio-telephones in the airplanes and all signals were by hand or visual, from one plane to the other that's the way they communicated."

Pilots conducted experiments in aerial observation of artillery fire at Fort Sill as they learned how to fly. They were trained in navigation and map reading. Many "aviation firsts" were achieved in signal corps, mapping and aerial photography, including the first aerial mosaic photo, which composite 42 photos into a landscape mosaic that was used for artillery fire direction. While they were experimenting with the aircraft, they discovered that the support struts on the planes were inadequate, so they made modifications during this testing period. They also beefed up the wing supports and landing gear struts.

Those modifications were made just in time.

"The 1st Aero Squadron was sent to Fort Bliss in 1916 to provide support for Gen. John 'Blackjack' Pershing's operations against Pancho Villa in Mexico. Villa had mounted a cross-border raid on the town of Columbus, N.M. Villa and his men had attacked a detachment of the 13th Calvary Regiment and killed eight Soldiers and 10 civilians. That began what was referred to as the "Border War" that lasted over a year. Pershing took an expeditionary force that included the 1st Aero Squadron. This deployment marked the first use of aircraft by any Army in tactical combat. "Things didn't go as planned," said Randy Palmer, airfield manager for Henry Post Airfield. The Army quickly discovered that early aircraft were not ready for desert combat because dirt clogged the air filters and the rough terrain damaged the landing gears. But the lessons learned back in 1916-17 would pay off 25 years later during the early battles of World War II.

"Most of the early planes were used for scouting and locating the enemy. Then they developed the ability to drop grenades and small bombs on the enemy. The planes that were at Fort Sill after World War I became the 'eyes' of the artillery so that they could direct fire down on the enemy. They found out they could train the artillery observers to go up in these little aircraft and adjust artillery," Palmer said.

Balloons were also used at Fort Sill for observation of artillery fire and battle. Originally used during the Civil War, they evolved from round balloons that were tethered in one place and used hot air for lift, to sausage-shaped balloons filled with hydrogen that could move under their own power.

"Right before America entered World War I, the Army formed the observation school here. Artillery officers would go up in these balloons, in the gondola basket, to observe and adjust artillery fire.

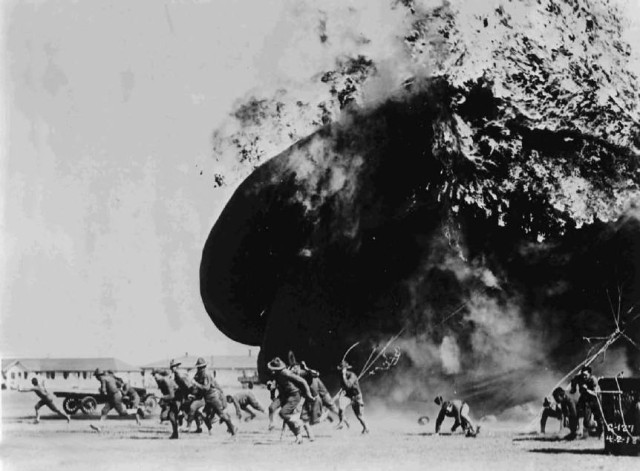

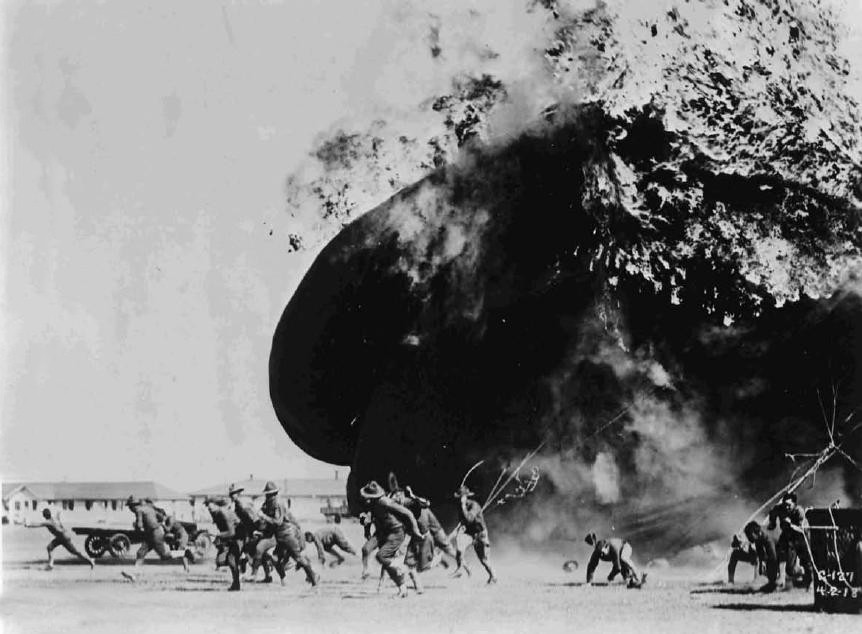

Hydrogen was the primary gas they used," Spivey said. It took numerous accidents, explosions and fires before the Army decided that hydrogen was the wrong gas for filling balloons.

"In 1918 there was a tragic accident at Henry Post field. A balloon filled with hydrogen was getting ready to lift off and the ground crew was still holding the guide ropes hanging down. Static electricity caused a spark and the whole thing blew up," Spivey said. "Soldiers initially ran away from the fireball but were ordered to go back towards the fire, to keep the balloon from drifting toward the wooden barracks in the vicinity. At least six Soldiers were killed and another 30 were injured in that incident."

"There had always been wooden balloon hangars here, but they would burn down. So they got the current all-metal balloon hangar we have, disassembled it in California, shipped it to Fort Sill in 100 rail cars and reassembled on its present site in 1935. Balloons were used throughout World War II," said Wayne Guffy, Henry Post Army Airfield operations officer.

Hovering was always the key issue, to do artillery observation more accurately.

And whether it was balloons or fixed-wing observation aircraft, or eventually helicopters, Fort Sill pioneered many of the techniques and equipment that the Army would use to help direct artillery fire for decades to come.

Fort Sill was to become the official "Birthplace of Modern Aviation" June 6, 1942, some 70 years ago. The War Department established the Department of Air Training , directed by Lt. Col.

William Ford. This group of 19 students, referred to as the "Class Before One" graduated that fall. Army aviation entered combat when L-4 "Grasshoppers" flew off of the USS Ranger aircraft carrier to provide support for "Operation Torch," the American beach invasions of Africa on Nov. 9, 1942. These tiny aircraft were used to provide aerial observation, adjust artillery fire, gather intelligence, support naval bombardment and even conduct direct bombing missions against German and Italian forces in North Africa.

"The Army had started using these 'liaison aircraft', the L-4 'Grasshoppers' for artillery spotting and directing fire, just prior to World War II. The pilots were trained at Henry Post Army Airfield and went into combat in late 1942. The enemy referred to these observation and spotting planes as the harbingers of death" because when they saw them fly over, they knew that artillery fire would soon follow," Spivey stated. "They were used throughout World War II and then were succeeded by the next generation of liaison aircraft, the

L-19 'Bird Dogs' in the Korean War."

Army aviation did indeed become so successful in World War II that in August, 1945 it was integrated into all combat branches of the Army.

The increased demand for Army aviators was so great that the Department of Air Training was deactivated and the U.S. Army Aviation School was established at Fort Sill June 6, 1953.

But just a year later, the Army Aviation School was moved to Fort Rucker, Ala., where it still operates.

Army aviation was not totally gone from Henry Post Field, though.

Beginning in the 1950s and on into the Vietnam War, various rotary-wing aircraft would be brought to Fort Sill to fulfill roles in aerial observation, reconnaissance and once again, directing of artillery fire on the enemy.

Guffy and Palmer were stationed here during those days and remember the role helicopters played.

"In the Vietnam War, they had what they called 'artillery raids.' They would hook up a battery of 105 mm howitzers under the Chinooks with all their ammunition and go out and clear the top of a mountain, drop the artillery in, shoot a fire mission and then get out of there because that would attract a lot of attention from the enemy. That was a tactic that we used with artillery," Palmer said.

Artillery's impact on Army aviation has been great. There may soon be new roles for Henry Post Airfield. Palmer explained that the Army is developing a program called JLENS.

"If it stays funded, Fort Sill could be one of the locations. It is a long-ranged radar and infrared surveillance system for controlling air defense systems, using blimps. It would link up with the Air Defense Artillery programs here at Fort Sill," he said.

Over the nearly 100 years of Army aviation at Fort Sill, the role of Henry Post Army Airfield has evolved.

From hot air and gas filled balloons, to delicate fabric and wood biplanes that were barely airworthy, artillery officers have braved the skies to help rain down artillery fire on opposing forces.

When the first airplanes came to Fort Sill in 1915, heavier-than-air flight itself was barely a dozen years old. So Fort Sill has adapted to the ever-changing needs of the Army and field artillery.

Now as technology is changing the future, there may be a new role for Henry Post Army Airfield.

Social Sharing