He was 18 years old and jobs were scarce. It seemed like an attractive option for the young man from Norwich, Conn., who was looking for steady work with a steady income and three squares a day.

Countless military careers may begin this way, but not many take the hair-raising, heart-pounding twists and turns Sierra Vista resident and retired Army captain Wilfred "Fred" Toczko encountered.

"I was too proud to beg, too honest to steal and too lazy to work, so what else could I do?" Toczko joked. "Well, I joined the Army."

He tried to enlist on his birthday in March 1939, but the recruiters told him the Army had no vacancies for privates.

"At that time, you couldn't just walk up and join the Army," he mused. A letter arrived that July, instructing him to report for duty in Springfield, Mass.

"When I enlisted, they said, 'Well, what do you want to do?' and I said, 'Well I'm Polish, so I want to be in the cavalry,'" Toczko chuckled. "But they were putting all the high school graduates in the Air Corps."

Although he was assigned as a bomber mechanic instead of cavalry, Toczko was able to choose his first duty station: Hawaii.

It took him two weeks to get to Hawaii by way of New York, the Panama Canal and San Francisco. When he and his comrades arrived in Hawaii, they rode the "pineapple train" to Wheeler Field, Oahu, where they learned basic Soldier skills such as donning gas masks and firing weapons.

From Wheeler, they traveled to Hickam Field, an Army Air Corps base adjacent to Pearl Harbor. Hickam was not yet open because it was still under construction at the time, so the Soldiers bunked in Hangar 5.

After a few weeks of performing menial tasks such as "area beautification," gate guard and nighttime fire watch, Toczko was assigned to the 72nd Bomb Squadron, and trained to be a parachute rigger.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, (then) Pfc. Toczko reported to guard duty on the flight line with his .45 caliber pistol and 21 rounds of ammunition.

"I got there a little early to make sure I was on time -- somewhere around 7:30 or 8 o'clock, and I saw an airplane come out of the sky, northeast of the airfield over the Ko'oloau Mountains," Toczko ruminated. "I thought the Navy was practicing 'reds and blues' again, and they're dropping practice bombs. I didn't pay much attention at first."

Then the bomb exploded and the sky seemed to fill with planes.

"From the ocean side, which is to the south of Hickam, came a bunch of Japanese torpedo bombers," he continued. "They're down on the deck at Hickam, maybe 50 to 100 feet from me, and there's this little, little guy in the back seat, shooting everything in sight with his machine gun."

Toczko began firing his .45 at the aircraft.

"I ran out of ammunition pretty quick," he said.

He ran back to the hangar, where people were beginning to assemble, and a Soldier in the armament shack helped him set up a .30 caliber water-cooled anti-aircraft tripod machine gun just outside. They were preparing to fire at the bombers when an infantry Soldier stopped them because they had no water in the reservoir.

"The operations sergeant and I ran into the hangar to fill it up, but the Japanese had mistaken our underground water tanks for fuel tanks and bombed them," he said. "So, we had no water in the hangar and we didn't know what to do."

The Soldiers' ingenuity took over.

"We grabbed a fire axe and broke-open the Coke machine, filled the reservoir with Coca-Cola, brought it out and fired the guns," he laughed, adding, "Things just seem to go better with Coke, don't they?"

Toczko sustained shrapnel injuries to his foot during the course of the attack.

"The next day, my best friend and I went to Bellows Field and were assigned to crew a B-18 [twin-engine bomber]. They went out every day on sub patrol, and the two of us worked on the airplane, living in a tent … cooking our own meals, basically camping out," he said.

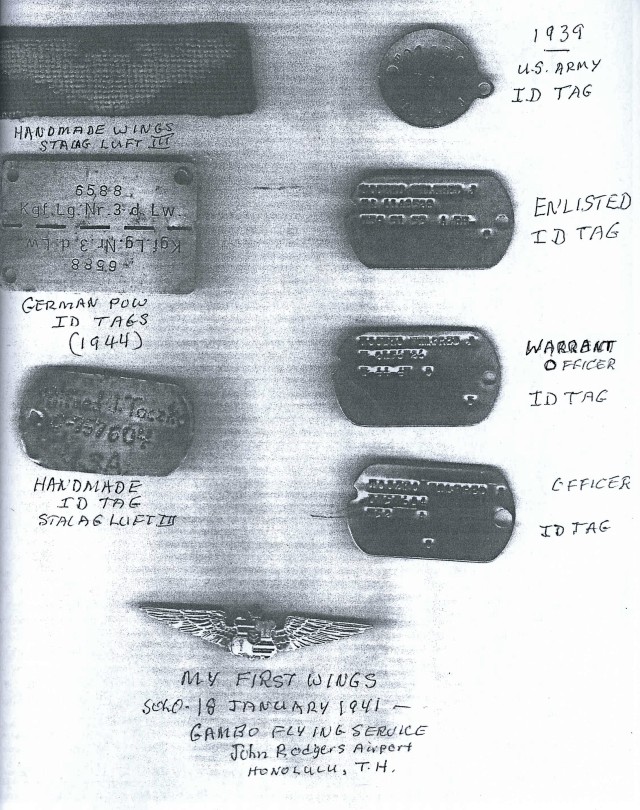

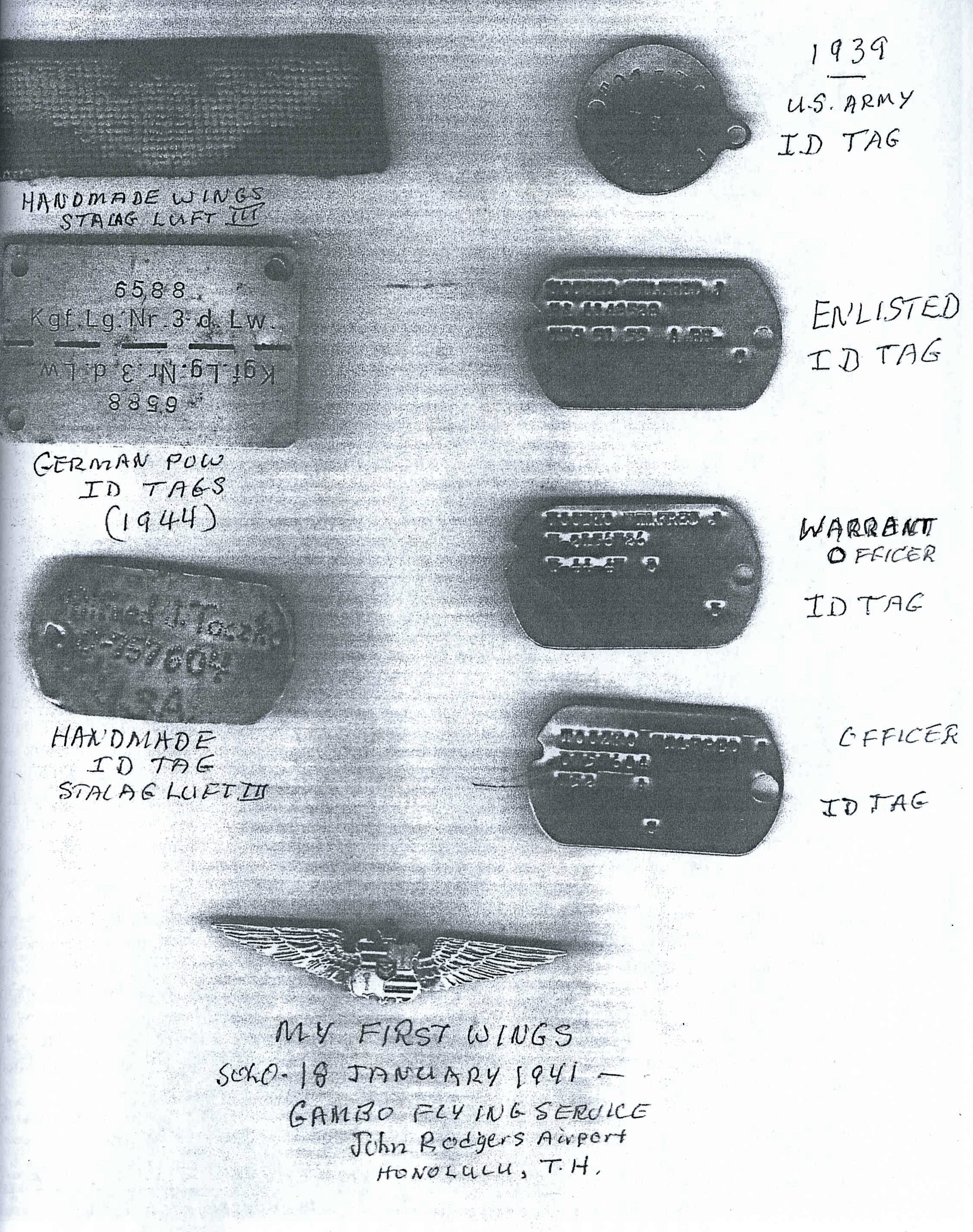

During his time in Hawaii, Toczko was also taking private flying lessons at John Rogers Airport, which he said was only a 600-foot strip at that time. Honolulu International Airport resides there now.

The Army Air Corps launched a new program allowing sergeants to become pilots, so he applied. A few weeks later, he was traveling with orders in-hand for flight training on the mainland.

As the war waged on, Toczko learned to fly glider planes and the B-24 Liberator bomber. He graduated from the Army Air Forces Pilot School at Stockton Field, Calif., on Oct. 1, 1943, was promoted to second lieutenant and transferred to Davis-Monthan Air Base in Tucson, Ariz.

Late February 1944, Toczko and his comrades were on their way to England to be bomber crew replacements for the Eighth Air Force.

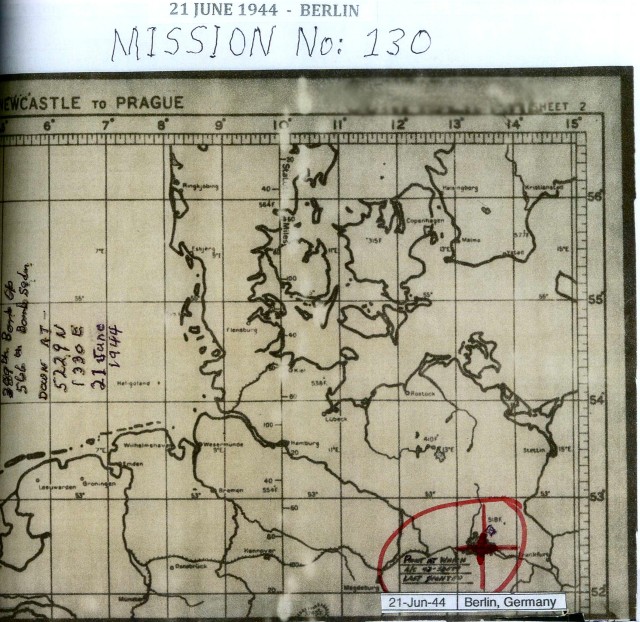

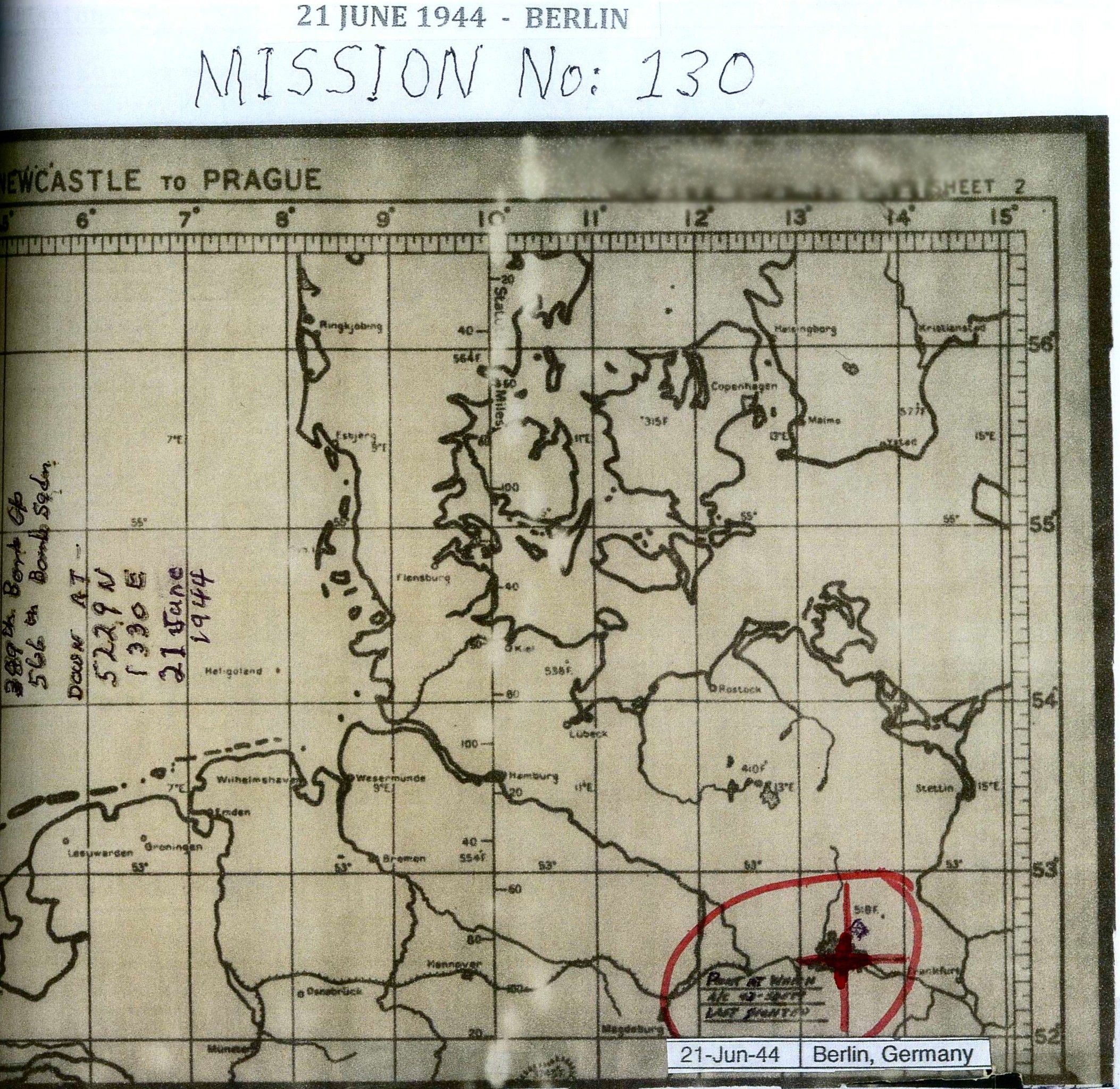

By May 7, 1944, he was assigned to the 566th Bomb Squadron out of Hethel, England, flying his first of 16 combat missions, to include flying in support of D-Day June 6, 1944.

Toczko's last combat flight was June 21, 1944, when the Germans shot down the B-24 he copiloted. He likened it to being attacked by a swarm of wasps, only much bigger and deadlier.

Toczko bailed out at about 10,000 feet as the plane entered a flat spin.

"Fortunately, we were flying with the bomb doors open," he reflected. "I think I was the last one out."

Toczko could not deploy his parachute immediately after jumping from the plane because

it was still directly above him. Once it spiraled past him, he pulled his ripcord.

"No sooner than I had gotten my chute open, then I fell under ground fire. A parachute doesn't hold air too well when there's holes in it," he joked.

"I had two bullets in my back … I've still got 'em back there," he added.

Somewhere between the plane taking fire and completing his life-saving, first-ever parachute jump, Toczko lost his shoes. His feet were scorched from the fiery aircraft; he had two 9 mm slugs in his back and he landed barefoot on Johannisthal airfield in Berlin, roughly 50 feet from the wreckage of his burning aircraft.

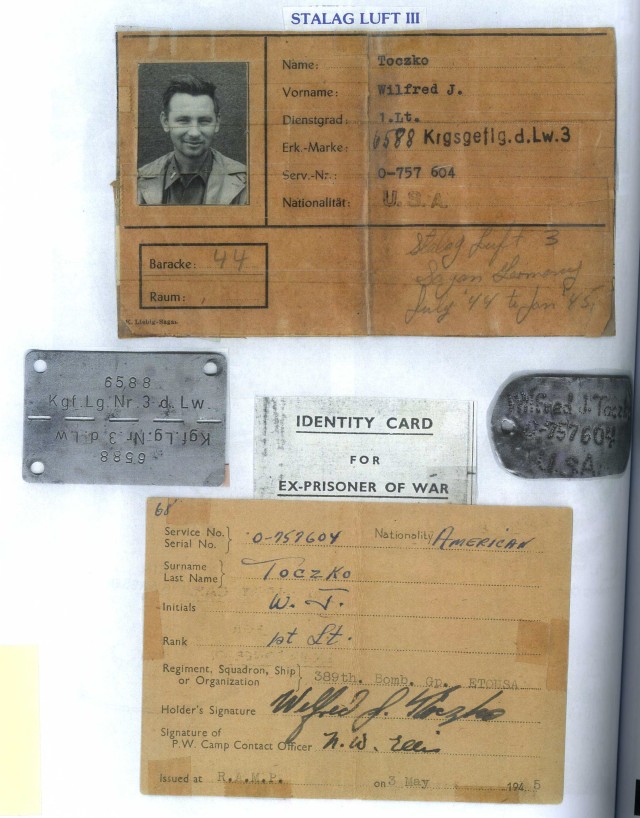

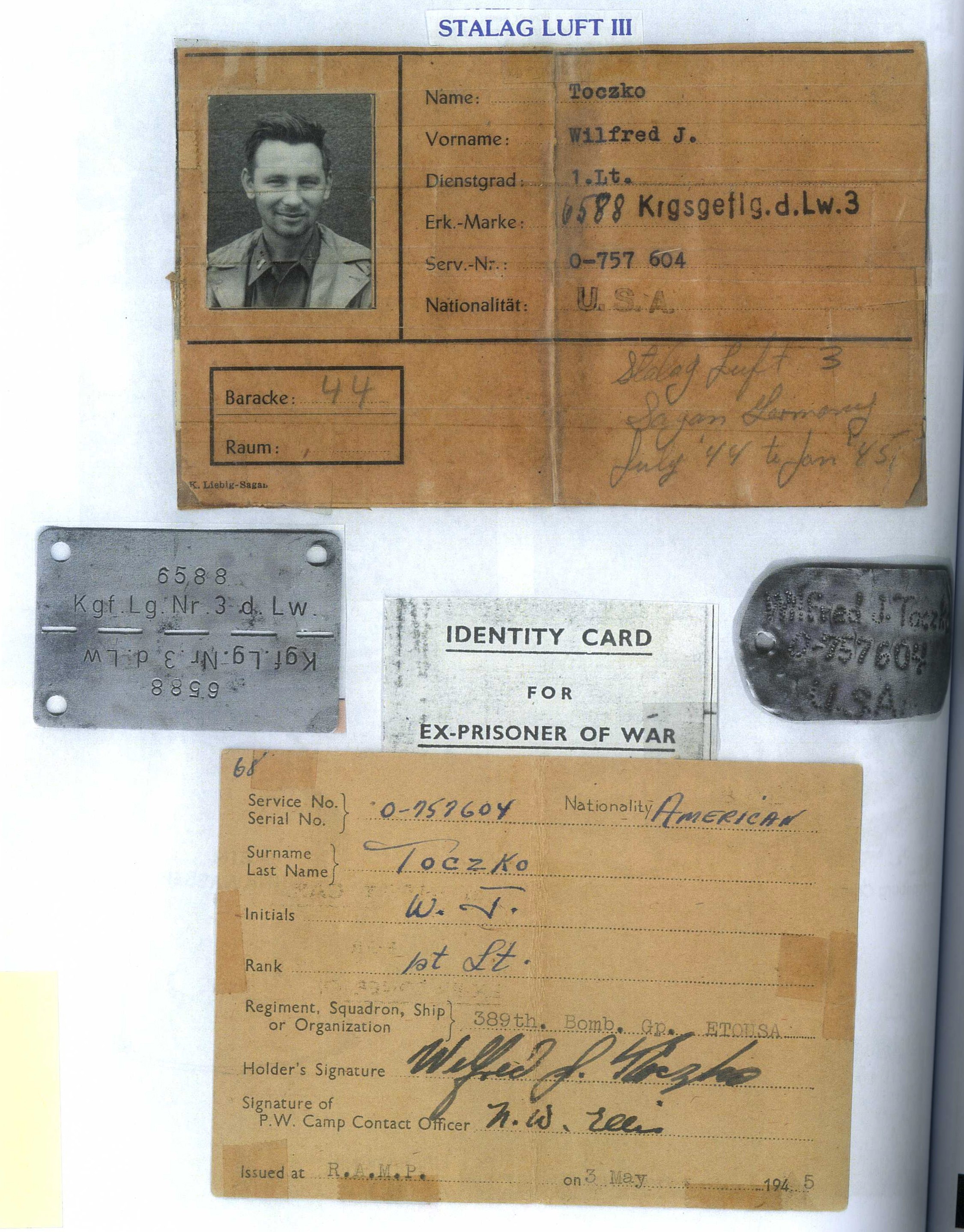

Toczco made first lieutenant the day the Germans shot down his plane.

"I guess you could say I dropped-in on my promotion," he said, laughing.

When the German soldiers realized Toczko was unable to walk, they arranged for an ambulance to transport him to Hermann Goering Luftwaffe Hospital, or what he called "the best hospital in Berlin," for treatment. There, he reunited with two of his crew members.

"[The U.S.] dropped bombs all during the day on them, and then at night, the British, the French, maybe the Russians and anybody else that wanted to drop bombs --and boy, those things, when they came down, it sounded like a freight train getting ready to come into a tunnel!" he exclaimed. "I have never been so frightened in my life. That's probably the only time I have ever been frightened about anything."

As the concussions shook the building, Toczko laid in fear because he could not yet walk. When everyone else evacuated to the bomb shelters, he was confined to his bed, listening to the explosions and hoping he lived to see another day.

He said they were treated very well at the hospital.

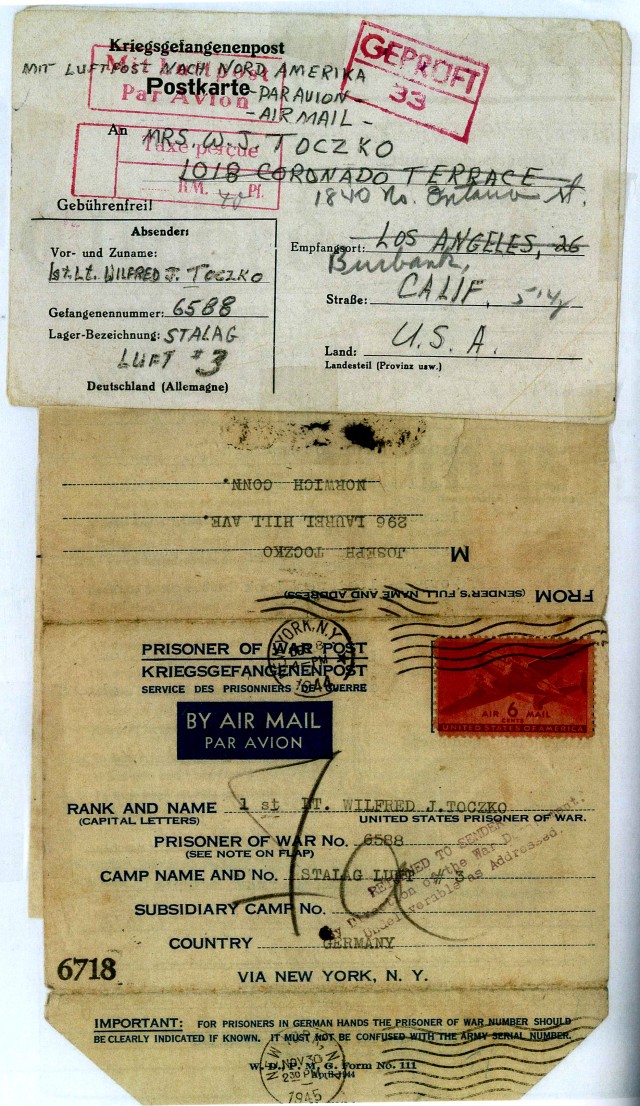

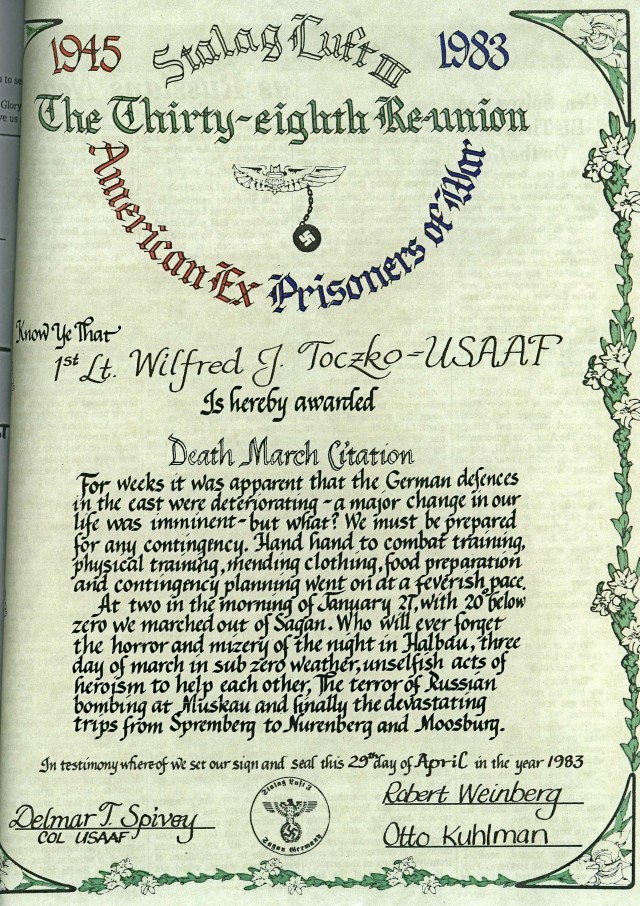

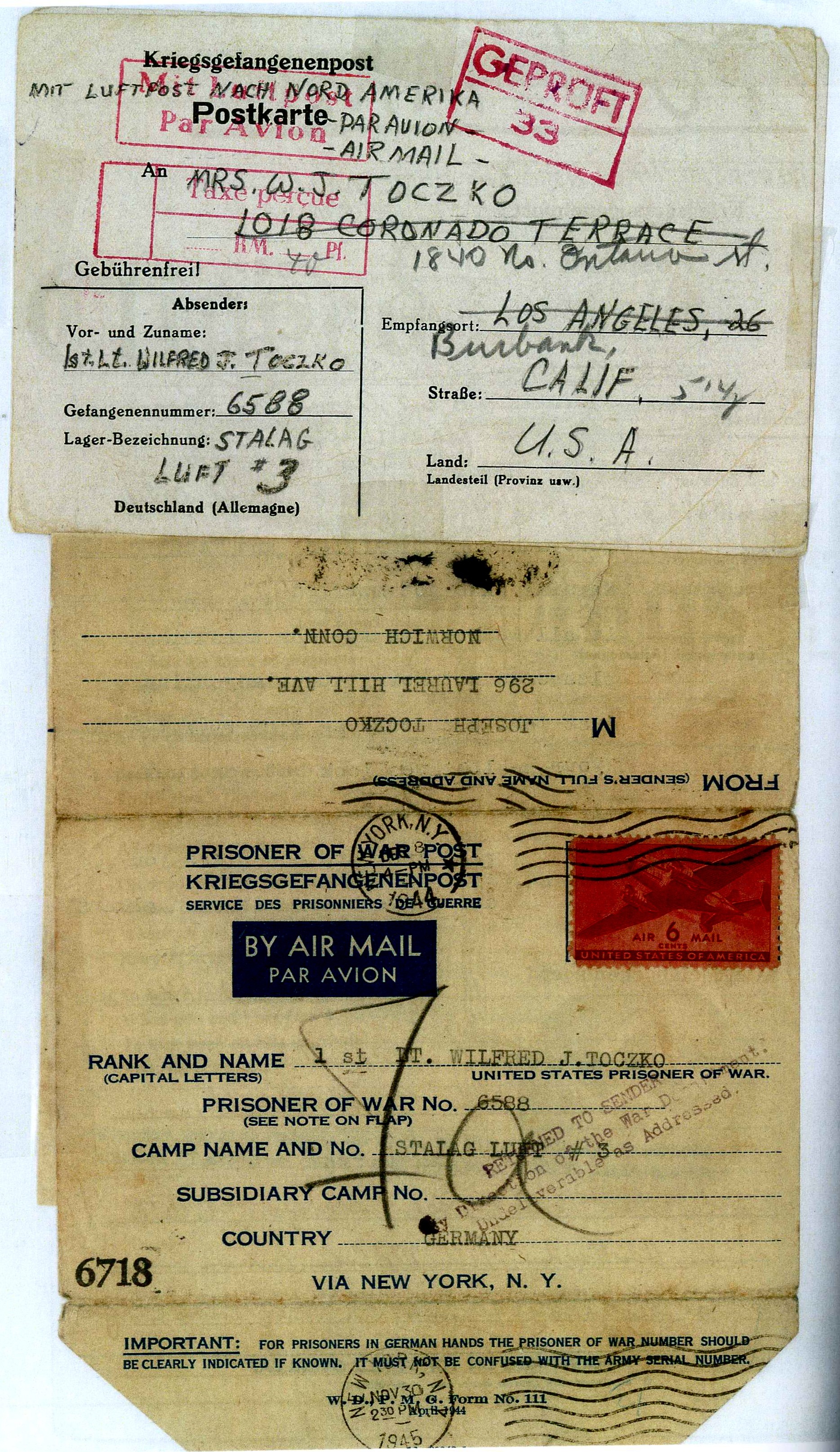

"As soon as they figured I could walk, they sent me over to Stalag [Luft] III, from 'The Great Escape.' We got there about a month after that escape," he said. Toczko also escaped once while he was there, and was recaptured.

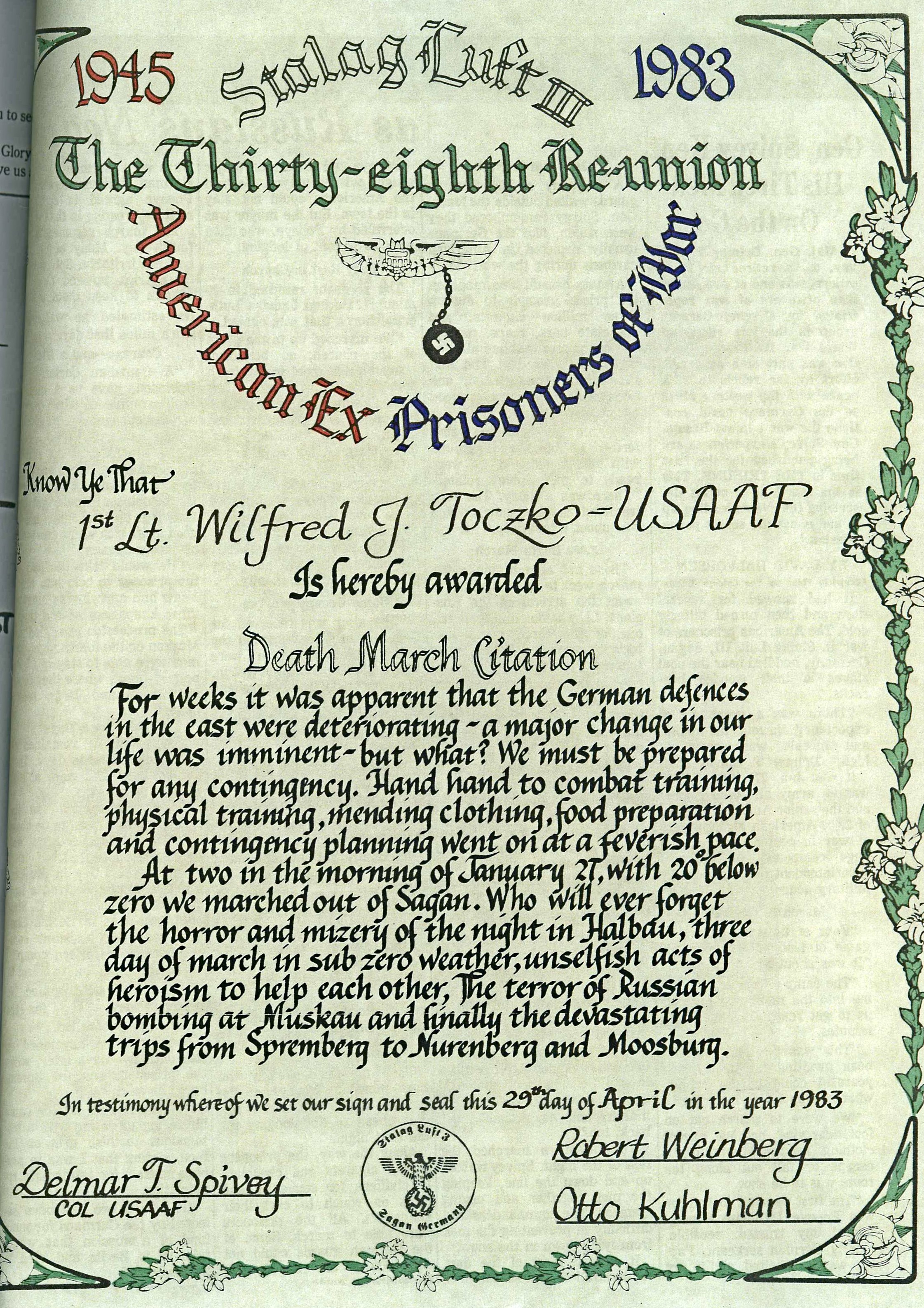

He also survived the l00-mile march in blizzard conditions with sub-zero temperatures to Stalag VII A, near Moosburg, Bavaria, ultimately sustaining frostbite on his feet.

On April 29, 1945, Toczko's 313th day as a prisoner of war, Combat Team A of Gen. George S. Patton's 14th Armored Division liberated the camp. The American flag flew over Moosburg at 12:15 p.m.

Toczko's story does not end there.

He eventually changed career paths and became a counterintelligence officer, which in turn, landed him an assignment back in Germany.

As a counterintelligence officer, he performed interviews and interrogations every day, in a building that was once part of a German prison camp.

"I did my job all day and would go home and cry all night," he said. "They didn't have [post-traumatic stress disorder] back then, so I didn't know what was going on."

The emotional stress put a strain on his marriage and his psyche. He considered himself a fairly emotionally-even man, so he was confused by his own weeping.

Toczko attempted to retire, but a year passed by before it was approved. Ever the professional, he continued performing his duties as required until they let him return to civilian life.

"I dropped their bombs for them, chased out their agents, did their security surveys," he said. "I gave them my loyalty."

Toczko missed being a Soldier and he could not stay away. Ninety days after leaving the military, he returned to the Army.

The ability to speak seven different languages was beneficial to his career as a counterintelligence officer. Much of the second half of his career reads like a story line from a James Bond movie.

He eventually "slowed down" and took command of an intelligence unit in Tucson, which also required him to maintain an office at Fort Huachuca.

He retired at Fort Huachuca as a master sergeant with 20 years and 14 days of service, and was later upgraded to the rank of captain. He then became a civil servant, continuing as a counterintelligence officer, and retiring after attaining the civilian grade of GS-13.

In March, Toczko will be 91 years old. His wars may be over, but he still battles symptoms of PTSD from time to time. He said he wants today's Soldiers to know that they can make it through the tough days, to "stick it out."

He said the key to his resilience is knowing the triggers and avoiding them.

Toczko has been completely retired for about 50 years now, and said he has seen and done everything he ever wanted to do in life. He extensively traveled the world, visited every continent except Greenland, piloted his last glider flight in Hawaii on his 83rd birthday and sold his last motorcycle after hip replacement surgery when he was 86.

"It's time to put my wings on the shelf and let the young ones fly now," he said, smiling.

Social Sharing