Time wields considerable power. It possesses the power to forgive, possesses the power to forget.

In times of tragedy, time often possesses the power to help heal.

It's been roughly eight months since tornadoes remade the landscape in parts of Ringgold, Ga., and Joplin, Mo., taking lives and taking the innocence of people once largely apathetic to storm warnings.

In some ways, time has begun to heal the wounds. The months since have seen an outpouring of goodwill, much of it from strangers across the country who have donated money, supplies and their time to help residents rebound.

There are other signs, too. Mounds of debris laden with the mangled remnants of people's lives have been cleared away, businesses are reopening weekly and homes are being rebuilt.

Alongside the hired hands and armies of volunteers helping people pick up the pieces have been Junior ROTC Cadets, who have spent countless hours clearing land, resurrecting structures, collecting donations and providing a sense of normalcy -- as much as normal can be now -- to those who need it.

By the time the EF-4 tornado and its 175 mph winds formed and touched down April 27 in the northern Georgia town, a beleaguered Sharon Vaughn, the Ringgold High School principal, was already reeling. Earlier in the day, the same line of storms devastated sections of Tuscaloosa, Ala., where her children live, and Vaughn had no word on their condition.

Trying to sleep away the worry, she was summoned shortly after the Ringgold tornado moved on by fellow school administrators, who had gone to her home that sat outside the twister's swath. She remembers being forced to focus on the havoc at home. She also remembers, amid the immediate chaos, finding some serenity in the sight of some Cadets and an instructor guarding the school from looters.

"That night, the Cadets were the only normal things I saw," said Vaughn, who later learned her children were safe. "Anytime I need them, the Cadets are there. When they were there that night, I had an idea that everything would be OK."

The tornadoes that barreled across Ringgold and Joplin collectively killed close to 160 people and injured more than 1,000 others in what went down as one of America's most active tornadic periods ever and the deadliest since 1950. Some 600 tornadoes touched down last spring nationwide, most of them concentrated in the Southeast.

As Joplin and Ringgold work to regain their footing, so too do the JROTC programs.

Tornadoes still dominate life in Ringgold and Joplin, and will for months and years to come. The scars -- physical and emotional -- are too deep still for even time to mend.

Work goes on to clear debris and reconstruct what used to be. But the mark of mother nature is inescapable -- the splintered trees, the once-crowded subdivisions that exist now as only a collection of concrete slabs, the forested ridge with a distinct canvas of leafless and downed trees where one twister cut a path.

Cadre and Cadets with both programs consider themselves lucky in that they survived, most with their lives, their families and their homes intact. But they weren't completely unscathed. They all knew someone who lost their home or suffered injuries.

Or worse.

Everyone has a story to tell.

JOPLIN, MO.

Whether by fate or sheer luck, third-year Cadet Sarah Stephens spent the evening of May 22 watching her boyfriend graduate Joplin High in a ceremony on the city's northwest side. Meanwhile, the tornado bore down on her home that sat directly across from the school.

As word of the twister and its movement quickly spread, Stephens knew she needed to get home. As panic set in, her boyfriend's mother tried to calm her, telling her everything would be all right.

It wasn't.

The force of the winds whisked away much of her home, including a dress she had bought a short time earlier she hoped to fix up and wear someday at her wedding.

Stephens could only make it to the start of her road because the street was blocked by debris. So she got out of the car and ran the rest of the way.

Stephens got to her house, now a pile of rubble, and frantically called out for her mother, younger brother and step-father, who were there when the tornado struck. She found them injured, but alive. They were buried under a slew of items, including a mattress, part of the bathroom wall, pieces of the high school roof and one of the goal posts ripped from the ground at the football field.

Stephens spent a half-hour digging out her family. Her mother, injured the worst of the three, suffered a broken foot that was crushed by the weight of the debris.

After pulling her out, Stephens fashioned a splint for her mother -- something she had learned in first aid training during JROTC classes -- using sticks and pieces of cloth she tore from her shirt. Then, once she knew her family was safe and receiving medical care, her instinct was to find and aid others in her neighborhood who were injured.

She quickly consoled a shaking and crying woman whose children were lost in the tornado.

"I told her, 'God will help,' " Stephens said. "That's the first thing that came to my head."

Looking back, Stephens said she's not so sure she could've coped well emotionally and would've been helpless had it not been for what she learned in JROTC.

"Just having the mechanical movements and knowledge of what to do kept me sane," said Stephens, who now lives in a nearby mobile home park that was developed shortly after the storm.

Joplin High School stood in the path of the EF-5 tornado that hit there and had little chance in the face of winds that topped out at 200 mph. Much of the building was obliterated. All of the windows were blown out, the gym collapsed, parts of the multi-story main building pancaked on each other and the JROTC classrooms were blocked by debris and then quickly overcome by an aggressive mold that flourished in the damp, warm environment that followed. All sorts of mementos, equipment and ACU uniforms were lost.

About the only items salvaged were a laptop computer, flags and a picture of Joplin's first JROTC class. Members of the program hope to go back into the school to retrieve a plaque that had been dedicated shortly before the tornado to the school's first enlisted instructor, Sgt. 1st Class Daniel Collins, who started the program in 1919.

It wasn't exactly the way retired Lt. Col. Paul Norris anticipated wrapping up his first year as the program's senior Army instructor.

Now he and his 190 Cadets are carrying out one of JROTC's lessons -- adaptability -- adjusting to life split apart. Seniors and juniors attend school in a refurbished part of the North Park Mall, while freshmen and sophomores go to the former Joplin High, known as Memorial, that's a 15-minute drive away.

Instructors shuttle back and forth to teach. Because the site for upperclassmen contains no gym, drill teams and color guard members must practice at Memorial at times that don't conflict with other activities. That means training at 6:30 in the morning.

The program has received financial assistance from Cadet Command's 3rd Brigade. But even when the program replenishes what it lost, Norris is uncertain how to logistically assemble all the Cadets together during the school day to get them measured and outfitted.

The split operations are taking a toll on the program, mostly from a developmental standpoint. Because juniors and seniors attend school across town, there is little interaction between them and new Cadets. A secondary chain of command, consisting of underclassmen, has been assembled to direct Cadets at Memorial.

"Unless those kids are on the drill team, there are kids there who don't even know their Cadet staff," Norris said.

It's uncertain what impact that might ultimately have on the program, Norris said. But until a new school is built that brings all the grades back together, he said leadership has to make do as best it can.

For now, there are no uniform days. But Cadets say they don't need uniforms to honorably represent their program and community.

Many of them served as security around the high school in the days after the tornado, keeping people from going inside what was left of the unstable structure.

"Nobody told us to," said Janene Woodruff, a junior and the battalion's command sergeant major. "It was just something we did."

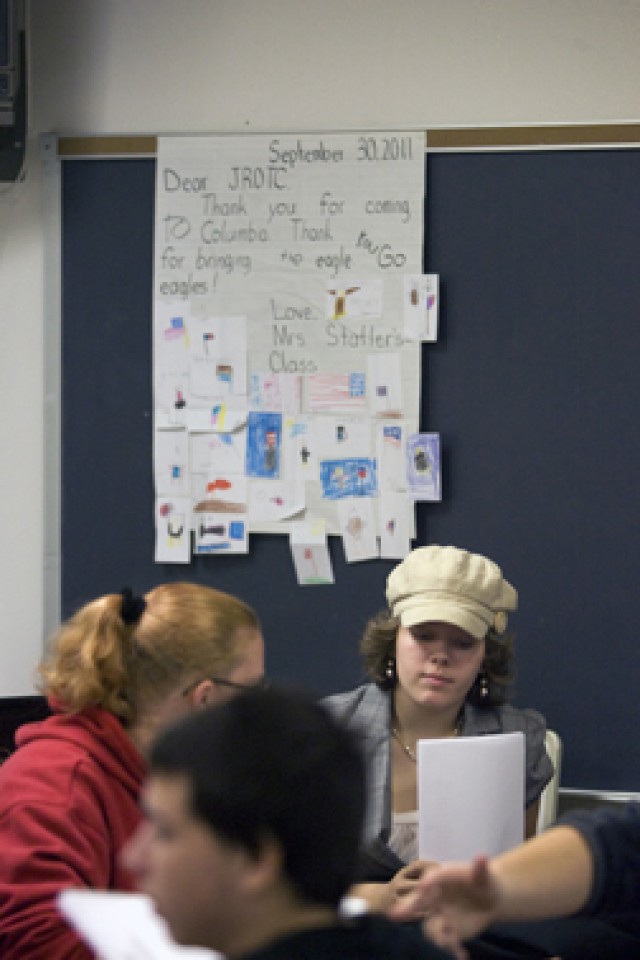

Perhaps the most indelible mark being left by the Joplin program is through an idea to take a chainsaw to the toppled trees of a grove outside the demolished high school and turn them into sculptures of eagles, the school's mascot. One was also carved into the likeness of a bear, the mascot of a former local high school that was merged into Joplin.

Cadets have spearheaded a campaign to put carvings, called Eagle Drops, in each of the city's elementary and middle schools and one will sit on the new high school campus, whenever and wherever it is built. They led fund-raising campaigns to pay for most of the carvings.

Cadets also are advocating for the construction of a local pavilion that would be dedicated to the donors and volunteers who helped after the storm.

"It's a way to remember what they did for us," senior Cadet Tanner Crawford said. "We've gone through it all, and nothing can stop us now. We want to do something great. Things like this pavilion will give us a lasting legacy. We'll make sure they remember us."

RINGGOLD, GA

After the tornado passed Ringgold, Cadets donned their uniforms and headed into the community trying to help. But because most were minors and because of the dangers that existed with gas lines spurting fuel and power lines blocking roadways, they were turned away.

So they went to their home away from home, the high school. Besides serving as guards, they helped man roadblocks to keep passers-by from streets littered with debris from the school that peeled away as the tornado pummeled the grounds.

Still, many of the program's 110 Cadets longed to be part of the recovery in any way they could. They delivered food to families in need and served as the color guard at an annual local prayer breakfast, which normally attracts a few dozen people but hosted nearly 700 earlier this year.

Those like junior Cadet Dayzi Green teamed with her step-dad to help people cut down and remove trees in the area.

"It was dirty and tiring work," she said. "I felt I actually made a difference. If we were in the same position, those people would've helped us."

Sophomore Austin Kiser learned to roof while helping a friend repair his home and cleared trees from the land, cutting it into firewood. He also assisted in reconstructing the side of a trailer for another friend.

"The Cadets knew what needed to be done, and they just did it," said retired Sgt. 1st Class Larry Sisemore, a Ringgold instructor.

"That is their nature," said retired Maj. James Creamer, the senior Army instructor. "This whole school has a helping attitude."

As donations from around the country flooded in, Cadets recently manned a large attic in a building where material was housed, sorting and distributing clothing and other items.

The JROTC offices on the far north end of the school suffered significant water damage, but little was lost. Because the tornado wiped out part of the south end of the school, the JROTC offices were used as storage while other sections were repaired and to keep supplies -- paper, pens and the like -- that had been sent in from around the country. There was so much of it, months later a good deal still sits boxed in Creamer's office to be used as needed.

Crews have since wrapped up work on the JROTC building, and Cadets are hanging posters and pictures back on the walls. They've returned to drill and Raider team practices, hanging out with each other outside the building long after the final bell. And in late-October, a number of them fanned out around the area surrounding the school to plant some three dozen maple trees as part of a larger Ringgold effort to bring new life to the community where lives were lost.

In the weeks after the tornadoes hit, many Cadets spent little time with others in their respective programs, focusing instead on getting their personal lives back in order. Returning to school for a number of them was something they eagerly anticipated, a chance to be with friends, get back to their educational routines and focus their attention elsewhere.

"We didn't really want to talk about it," said senior Jordan Clark, a member of the Ringgold color guard. "We just practiced. It was a way to get away from the fact that half the town was gone."

Having experienced such widespread tragedy has brought Cadets within the Joplin and Ringgold programs closer. Many say they're quicker to set aside differences with others, more open to meeting new people and more aware of what might head their way when the skies darken.

"I knew tornadoes could be destructive," Stephens said. "I just didn't know how bad they could be.

"Having your friends there helps, but you never get over something like this."

Time will tell.

Social Sharing