FORT MEADE, Md. (Army News Service, Nov. 10, 2011) -- Nearly 71 years after President Franklin D. Roosevelt laid the cornerstone on the tower at Bethesda Naval Hospital, Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta cut the red ribbon, Nov. 10, officially opening the new Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

A result of the 2005 Base Realignment and Closure, the newly enhanced facility is now staffed with Navy, Army and Air Force personnel.

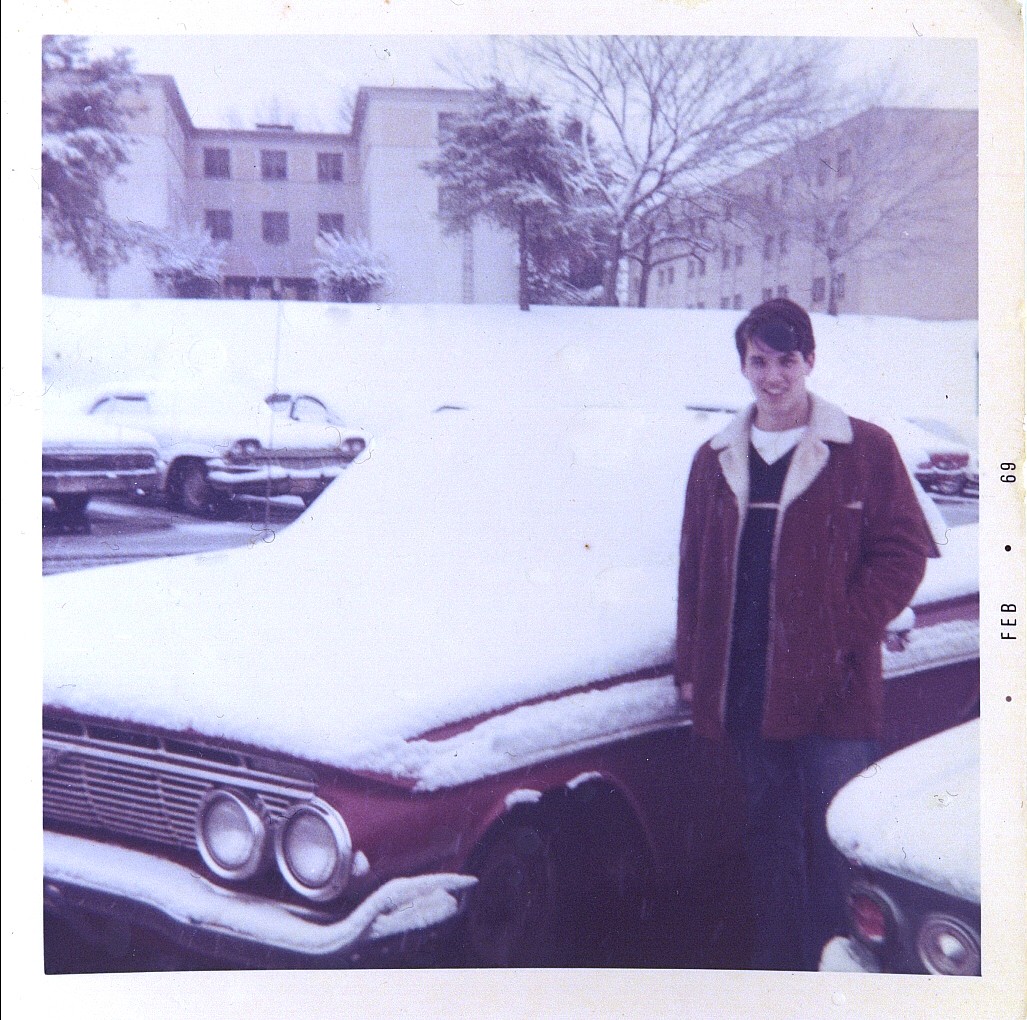

But in the fall of 1968, a bunch of us young Sailors who had just graduated from Great Lakes Hospital Corps School near Chicago and had gained six months of ward duty experience at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, reported to begin Operating Room Technician School.

In the beginning, we called the edifice Mecca -- the be all and end all of medical training, and woe to any tech who had trained at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, Va.

We considered ourselves to be the best as we circulated and scrubbed through every operation of the body: plastic surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Neurology, Cardiology, Inhalation Therapy, Orthopedics and Amputations, Physical Therapy and Ophthalmology.

At the end of six months of intensive training, often 12 hours and more a day, we knew every instrument's name and its use, we had studied with the surgeons at the National Library of Medicine across Wisconsin Ave. from the hospital, and we knew every idiosyncrasy of each surgeon.

When not scrubbing in surgery, or buffing the O.R. hallway, we took turns traveling to Andrews Air Force Base to get patients off of MAC (Military Airlift Command) flights, 13 hours after being shot in Vietnam, brought them into surgery where we prepped them, anesthetized them and often cleaned out maggots that had been placed on the wounds to eat away the dead tissue and keep the blood flowing.

Three surgeries come quickly to mind when I remember training at this hospital -- an aorta needing repair, a simple procedure that suddenly turned into a splenectomy, and my first C-section.

I was having lunch in the mess hall when this loud nurse came through the large room hollering my name. "McIlvaine, McIlvaine, where are you?"

I thought good God, what's going on? I forgot to properly cover the orange sticks? I left a 4" X 8" gauze lying around....?

"McIlvaine, didn't you hear me?"

"Sorry, ma'am," came my feeble reply.

"You need to come with me, immediately. A woman has a prolapsed cord and she's coming down to surgery now. You need to come and scrub up, NOW!"

My stomach knotted and my heart raced. The National Naval Medical Center was and still is a teaching hospital and the operating room theater is exactly that.

I scrubbed my hands and arms, rushed into the O.R., was assisted into a gown and gloves and immediately tended to my back table and Mayo table, making sure I had all the clamps and sutures, needles and retractors.

I looked up to see nurses and interns looking down from the glass dome above and the room filled with people as I heard the screams of the woman being pushed down the hall. A doctor was on the gurney with her, between her legs with his arm inside her, pushing to keep the baby from tightening the cord around its neck.

It could not have been more than a minute when the baby emerged from the uterus through her belly and was being handed off to a pediatrician while we immediately began sewing her up after delivering the placenta.

I actually had a tear in my eye as I saw my first delivery, whether Caesarian or vaginal.

The second surgery, a simple repair, was my first witness of ego and disaster. The surgeon, inflated with his own wonderfulness, was showing interns how surgery is really done. I offered the necessary retraction but he refused, boasting how he could use his fingers the old-fashioned way.

His "way" resulted in pulling on the splenetic artery and ended up becoming a splenectomy. His reputation went far and wide and I was chosen to scrub with him because I had a knack of moving quickly when he didn't like the #20 skin blade or Joe's Hoe -- a heavy device used to facilitate easy access.

But I saved the best for last.

This was my admiration, at the age of 20, for a female surgeon whose eyes burst forth with incredible beauty over her face mask.

"Call me Diane," she said as she opened up a gentleman who had an aorta needing repair.

"OK, Diane," said I with an air of dashing Errol Flynn, as I passed some suction or a sponge or a needle on a needle driver to her ... I really can't remember.

"Hemostat, please," she said as she looked up to me from her work.

"Yes, Diane, anything you want ...," no, I couldn't have said that ... I just placed the instrument in her hand and watched as her fingers gently took it from me.

This procedure was another operation that was over too quickly.

So, I envy those who are currently being trained at the new Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda and I know the patients who go through those halls I once scrubbed, and the newly constructed and renovated space of about 2.4 million square feet of clinical and administrative space, will get the kind of care they deserve in operations that, hopefully, are over too quickly so they can get back into a life filled with their new-found freedom from pain and debilitation.

Social Sharing