FORT MEADE, Md. (Army News Service, Oct. 31, 2011) -- Although November was not designated as National American Indian Heritage Month until 1990, I grew up knowing about my Indian heritage by hearing stories from my mother, who was born to a French woman from Quimper and an Indian descended from Chief Black Hawk.

I and my Sac and Fox cousins didn't play cowboys and Indians growing up. We played at "taking back our land and restoring our nation." We imitated our ancestor who tried to do that in 1832, giving the future President Abraham Lincoln his only battle experience during the Black Hawk War.

We knew we were playing, however, because like so many of those who had gone before us, not only had the names of Indian places and people become destinations and football team names, the people had become assimilated, too.

It's a fact of life.

After warring with people, we all begin to become "one", even though some insurgents take longer than others to understand this rite of passage. Or, as we jokingly said of ourselves, "our Indian blood had become polluted."

For instance the Lenni Lenape, better known as the Delaware Indians, had assimilated long before William Penn came to Philadelphia on his ship, "Welcome."

However, when my grandfather, Wapahmak -- Dark Shining Object on Still Water -- took me fishing or watched me play football, I knew the eyes of my ancestors were upon me. When we played at war and performed stunts, such as diving through windows, climbing rock walls, swimming in cold springs, catching fish with our hands and holding onto electric fencing, we knew we were testing ourselves.

My Indian grandfather did the same but it wasn't play. He was a deep-sea diver in World War I and a ship fitter in World War II and then he built radio towers outside of Philadelphia.

Indian men always wanted to prove themselves, but when war ends, they take jobs considered too dangerous by many.

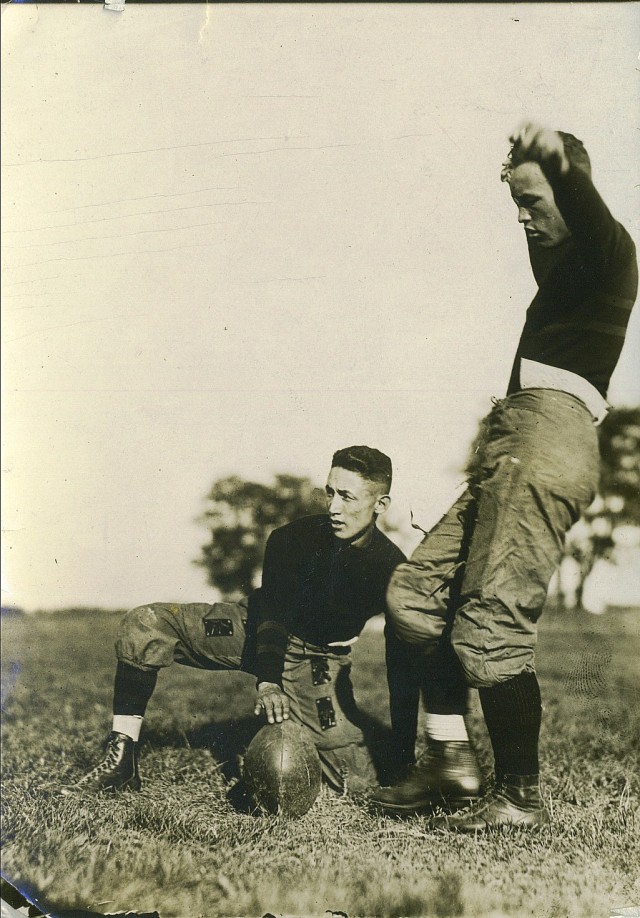

Before that, my grandfather attended the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania -- founded by Capt. Richard H. Pratt in 1879. There my granddad played football with his cousin Jim Thorpe.

So, even though Pratt's effort to take the Indian out of the Indian had, in large part worked, my cousins, disbursed by marriage and opportunity from our tribal lands in Shawnee, Okla., still held on to both sides of our heritage.

And then, in 2002, I had the opportunity to be executive producer for the National Museum of the American Indian on the mall, near the U.S. Capitol.

While my mom -- First Ray of Dawn, and granddad had both been given Indian names at birth, the museum experience gave me the opportunity to reconnect with my ancestors many years later.

During my time at the museum, through my sponsors Grace Thorpe -- Jim's daughter, Bud McClellan, and other elders of the tribe, I was given the name Ni-Ka-Noo-Ko-Huk -- Leader when Lightning Strikes. I became a member of the We mi ko (Thunder) Clan, and also was invited to dance with the Gourd Clan because of my military experience.

I hired a TV crew and we traveled through Canada from Montreal to Winnepeg and from the Virginia tribes to Oklahoma, New Mexico and up to Washington state and got the chance to dance with a group of Indians in Chicago.

I was hesitant to join the other dancers because I had once told a cousin that I didn't know how to dance. His answer to me was, "that's alright, no one knows how to dance ... only God knows."

My film crew and I interviewed members of the Kahnawake Mohawk territory, many of whom built the Empire State Building and the World Trade Center. This powerful tribe stood up against the Canadian police when they refused to make French their first language.

This was the first time I had heard of Indians re-learning or holding onto their language -- or that which makes them Indian. The tribe had an elementary, middle and high school where children were immersed in the language.

We made friends with the Tohono O'odham reservation near Tucson, Ariz., which began a non-profit organization called Native Seeds, and we were invited into a home to eat the results of their labors as they promoted the use of ancient crops.

We journeyed to Yakama Nation and visited Mount Adams -- their source of water and irrigation for their crops and lumber mill, and saw salmon fishing along the Columbia River in Washington.

We also visited the relatively small Hoopa Valley Tribe where they showed us how they cut the river grass to make baskets, and took a boat ride up the majestic Trinity River in northern California where we saw eagles soar.

We saw tribes and nations with many resources and some striving to hold on to what they have. Some shared their art and music while others shared the fruits of their labors. But all had pride in their heritage.

Not unlike the Pow-Wow, where the people get together to join in dancing, visiting, renewing old friendships and making new ones, and to preserve their heritage, the Native Americans we met across North America knew the importance of sharing their past, present and future with others at the National Museum of the American Indian which officially opened in 2004 with a national Pow-Wow.

Once many of the tribes raided and fought against each other. Now they gather together to keep a people alive ... to prove we are still here and we still have a voice.

Where once there was mutual honor and respect for the enemy in battle, this now has evolved into mutual honor and respect for each tribe, nation or native community. We work with each other to keep alive the language, the song, the dance and the beat of the drum.

Social Sharing