Harry DeSmet Thompson is one of the 10th Mountain Division's oldest surviving "muleskinners."

He was a tree surgeon living in Boxford, Mass., with a wife and two young daughters when World War II broke out. Not to be "outdone" by three of his seven brothers, who were already fighting in England and the South Pacific, he entered the Army Feb. 1, 1944, at the age of 35.

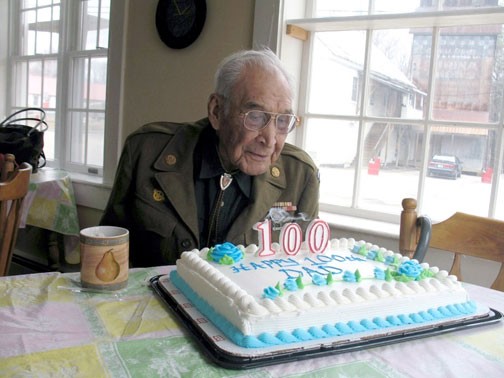

"I decided I better do my part," the 102-year-old veteran said during a recent interview at his home in Tamworth, N.H. "I didn't want my younger brothers to have anything over me."

After boot camp at Fort Bragg, N.C., he was assigned to the 10th Mountain Division's 605th Field Artillery (Mule Pack) Battalion, which supported the 86th Infantry Regiment with munitions and supplies in the Apennine Mountains of northern Italy.

Muleskinners were tasked with the difficult duty of keeping their string of mules in line. Thompson said five mules typically carried one 75mm howitzer gun emplacement, while at least seven mules were needed for the 105mm howitzer. He explained that the key to keeping a pack of mules on the straight and narrow was building a rapport with them.

"At first, you got to get acquainted with the animal," he said. "You make your presence felt often. Walk around him, rub his back, water him, feed him -- you're trying to get that mule to know you. "After that," he added, "you got to learn how to put the packs on him and cinch them up good and tight, so if he acts up, nothing will fall off."

Thompson recalled that during his first training experience in Camp Swift, Texas, he inherited an ugly and untrustworthy mule. "He had a weird look on his face," he said. "We called him Fish Face. We called him other fancy names too that can't be repeated."

Fish Face regularly stood on its front feet to kick Soldiers. Thompson said after it broke one private's arm, nobody wanted the belligerent beast. "But I took him on," he said. "He dragged me around a few times, but I stayed with him. We got on pretty good afterwards."

Thompson was the oldest of 12 children born to Mary "Mamie" DeSmet Thompson, the great-granddaughter of Lewis and Clark Expedition explorer Meriwether Lewis, and Harry William Thompson, a Teton Sioux Indian. He was raised in the Fort Hale District of the Lower Brule Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, where hunting, trapping, fishing and fetching fresh water from the Missouri River were everyday occurrences.

"We didn't buy meat very often," he said. "But we did buy a lot of ammunition."

His favorite meal was jackrabbit hash. During harsh winters, he said his mother could stretch out the hash for his large family over several days using just two jackrabbits.

Thompson's skills were not limited to the outdoors. His knack for being a quick study landed him in a prominent elementary school in the high country, or "flat," where white farmers sent their children.

He later was sent to high school in Santee, Neb., a boarding school run by American Missionary Association teachers about 150 miles down the river from his home in South Dakota. During his last year there, he met his future wife, Dr. Doris Sidwell -- a University of Vermont medical school graduate who left her job at a Massachusetts hospital to be the first physician at the school in Santee.

The men of 605th FA Battalion boarded the USS General M.C. Meigs troopship and departed Newport News, Va., Jan. 6, 1945. Troops aboard the USS Meigs, one of many ships in the convoy, did not learn of their destination until they were well out into the Atlantic. During the 13-day journey to Naples, Italy, Thompson said the seas were often rough. He remembered looking out portholes from where the Soldiers stood at tables to eat, and watching the destroyers appear and disappear in the trough of the waves.

Thompson said he will never forget the sick Soldiers lined up one day along the railing of the ship that caused one officer to take notice. "'Weak stomach, eh?'" Thompson recalled the officer asking one pale fellow. "'No sir. I'm throwing it as far as the next guy.'"

From Naples, the Soldiers were transported more than 300 miles up the coast to Livorno on landing crafts. Thompson said he remembers the bottom of their smaller vessel periodically scraping sunken German ships in the harbor when they arrived.

Other divisions had previously been sent into northern Italy. Thompson said the 10th Mountain Division was Allied Forces' third attempt to rout the Germans.

The mules Soldiers used for training at Camp Swift had stayed in Texas so as the division moved in, mules were rounded up and transported to the war front from southern Italy. Thompson noted Italian mules were smaller than American mules and couldn't bear as heavy a load.

Although Thompson's background in breaking wild animals on his father's ranch helped him outsmart even the most intransigent of mules, an incident in Italy with his best friend, Godfrey, left him partially crippled.

It happened one day after his unit had been ordered to train mules near Rome, where the war had torn much of the countryside apart. Godfrey picked out a mule to ride and asked Thompson to lead it.

"But that mule shot right out from a dead (start) without any warning," Thompson said. "I tried to run fast enough to get some slack in the halter rope so I could plant my feet and pull the mule back. In the process of doing that ... my knee bent backwards."

Godfrey cared for his bed-ridden friend after the mishap, and Thompson said he would always remember his friend's kindness and concern. He lamented that Godfrey, whose last name he cannot recall, died during the war and is most likely buried at the Florence American Cemetery and Memorial in Florence, Italy.

Because the 605th FA Battalion rarely remained in one place long, Thompson said mail from the home front often took a while to reach them. When there was mail call, Soldiers eagerly waited for their names to be called. Thompson considered himself a lucky man: His wife wrote him two letters a day. "I had an armful of letters," he said. "Some of the boys never got any letters."

How Thompson, the son of a Sioux culture known for its hunter-warrior traditions, won the love of Dr. Doris Sidwell of Harwinton, Conn., was quite fortuitous. As the only doctor for miles and miles, Sidwell was often required to drive her Ford coupe over hazardous wagon roads to make emergency house calls to families on ranches and farms in outlying areas of the prairie.

As fate would have it, the school principal directed the older male students like Thompson to accompany Sidwell.

"I guess I pushed her out of more mud holes than the rest of them," he said with a grin.

As she became more acquainted with Thompson, Sidwell periodically let him listen to the radio in her room, which is where he first heard an advertiser looking for "strong, young, outdoor-minded men who want to become tree surgeons." Thompson followed up and wound up working for Davey Tree Expert Company.

When Sidwell's father became gravely ill, the love-struck Thompson transferred within the company to the East Coast and looked after the family chicken business in Harwinton while also becoming better acquainted with his future in-laws, Stephen and Helen Sidwell.

One of Thompson's daughters, Jane Thompson Witzel, said her parents' love affair endured for 62 years, until Doris' death in 1994. Because of their very different upbringings, Witzel called their union a unique one.

"They both came from such diverse backgrounds," she said. "(But) they were both very forward-thinking and very ahead of their time."

During World War II, Witzel recalled her mother coming home from her job as a psychiatrist at Danvers State Hospital in Massachusetts and reading war letters at the dining room table to her and her older sister. She said her mother craved every tidbit of information from the war front and often put off sleep for the sake of the latest news report.

"As a very young child, I can remember my mother, having worked all day, staying up until the last word from the front came over the big, old wooden radio," she said. "That's when she would finally go to bed."

Thompson's recollection of the letters he mailed is a secret code he had previously worked out with his wife. He said if it began "Dearest Doris," it meant the first letter of every line would spell out the town from which he was writing. "That beat the Japanese code," Thompson said with a chuckle.

Thompson first heard about the elite 10th Mountain Division from men at a local barbershop in Boxford. He solicited three letters of recommendation, which the newly formed division required, and his request to join was honored.

He was in boot camp while his future unit finished alpine training in the Rocky Mountains, so he caught up with them for flatland maneuvers at Camp Swift, Texas. "I didn't get my mountain training," he said. "I had my mountain training on the job in Italy."

As the mule pack headed to the front, Thompson recalled being "tormented" for days on end in one location by German mortar fire. Allied Forces eventually flew a P-47 Thunderbolt into the region, and Thompson recalled watching the fighter plane strafe the ground nearby. "After that, we never heard from those Germans again," he said.

Days later, he carefully investigated the bombed-out area and discovered a mortar position that had been concealed by the Germans with a log roof, sod and small trees. Thompson entered the dugout through a zigzagged opening and was amazed to see maps of nearby ridges and enemy positions etched in makeshift walls.

The battalion was soon ordered to march up a ridge that was littered with the wounded and burning military vehicles. Thompson dug a deep foxhole and waited. In time, with the Germans on the run, the 10th Mountain Division chased the enemy across the Po Valley. While Thompson was in Lake Garda, commanders announced the war in Europe was over.

Thompson recalled a frightful experience he had one rainy evening on guard duty after the unit turned their mules over to the Italians.

His company bivouacked by the roadside and Thompson was put on the midnight shift by his platoon sergeant "again." He observed a light go on and off in a mess tent that was off limits. With his M1 Garand slung over his shoulder, he peeked in. "A form in front of me rushed me," he said. "I could tell by his movements, he was going (to try) to knock me out."

Thompson wrapped his arms around his attacker, pinned his arms and lifted him up before slamming him on his back. He got his knee up in the large man's throat. When Thompson grabbed his flashlight, he was shocked to see captain's bars on the man's shirt collar. The captain threatened to have Thompson court-martialed. But because Thompson had properly discharged his duties, his command backed his actions and the captain was reassigned.

During the war, two of Thompson's younger brothers serving in the Army in the South Pacific were severely wounded. Infantry point man Carl "Victor" Thompson survived a shot through his mouth, while machinegunner Elgin Harold Thompson survived severe shrapnel wounds to his hip.

"Leroy's the smartest of us all," Thompson said of his third brother who fought in Europe. "He joined the Air (Corps)."

Witzel, Thompson's daughter, still has a box of seashells her father picked up for her in Lido Beach, Italy, after the war, as well as silk scarves and a perfume bottle he bought for her in Venice.

Although she was young at the time, she can remember the excitement on her mother's face when her father called from Virginia and said he would soon be at the bus station in Lawrence, Mass., a large mill town on the Merrimack River. Making the occasion even more exciting, V-J Day was announced while her father was en route.

"Of course, word spread like wildfire," Witzel said. "All the bells in the clock towers in all the mills for miles around started ringing. I can remember a flood of thousands of happy people pouring out of the mills."

Thompson received such an enthusiastic hug and kiss from his wife that she accidentally cut his cheek with her glasses, scarring him for life with the memory of their happy reunion.

Cpl. Harry D. Thompson was honorably discharged from the Army Nov. 19, 1945. Five years later, he moved his family into a 150-year-old farmhouse nestled on the Bearcamp River in Tamworth, where he still lives today.

He toiled for many years to turn a majority of the rough 20-acre pasture into fertile land. His farm eventually became legendary in the region, mostly for its sweet corn, strawberries and asparagus. He also grew and sold everything from lettuce, spinach, cucumbers and beets to peas, beans, potatoes and seasonal squash. Freshly picked leftovers not sold at a deep discount were disbursed to churches and the local senior center. "His fields were handled to perfection, with every row laid out with military precision and never a weed to be seen," Witzel said.

In addition to his farming, Thompson never ceased perfecting his boyhood trapping skills. He trapped fox, mink, otter, fisher, bobcat, coyote, raccoon and "a lot of beaver" on Bearcamp River and in the nearby Ossipee Mountains. Thompson's reputation as an expert trapper and a registered guide led the New Hampshire Trappers Association to officially induct him into their Hall of Fame 10 years ago.

Thompson's journey through the 20th century and beyond has been remarkable. The living legend survived diseases and the extremes of nature on windswept prairies, fought a war on a mule in the mountains of Italy, and taught younger generations for decades many tricks of his trade. He described his own life like a film reel running in his mind.

"Deeply, it makes me feel good," he said of seeing so much in his lifetime. "Since my wife passed away, I've been living here alone. And all I have to do ... is close my eyes, sit back and start thinking. And it's like a great big movie ... places I've been, places I've seen -- all kinds of things I still do."

Paul Steven Ghiringhelli is a staff writer for the Fort Drum Mountaineer.

Social Sharing