Retired Chief Warrant Officer 4 Daniel "Dan" Laguna should be dead.

The former Green Beret should have died several times, actually.

But he survived skydiving and car accidents and horrific helicopter crashes and came back stronger each time because he had something to prove.

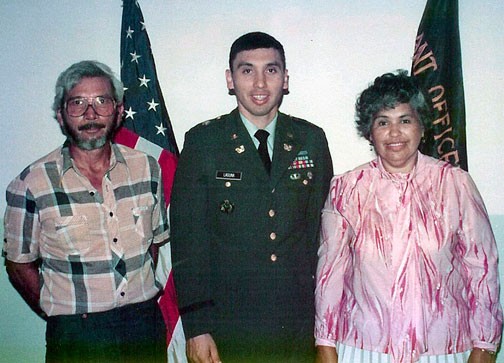

Of Mexican-Indian descent, the son of poor farmers from Rio Linda, Calif., was the first minority kid many of his classmates had ever met. They teased him and bullied him. Even his teachers said he would probably end up in jail, or at best "flipping burgers" for the rest of his life.

"Those comments only served to make me more determined than ever to prove them wrong," he later wrote in his memoir, "You Have to Live Hard to Be Hard." Laguna also had a proud family legacy of service and sacrifice as an example. Not only were two of his uncles killed while serving in the Pacific during World War II, his father, Daniel Laguna Sr., was a wounded veteran.

Blown upward after stepping on a land mine that killed most of his men, he "cussed all the way up and prayed all the way down," he told his sons. Badly burned, the elder Laguna barely survived, and spent years in the hospital. He still loved the Army, though, and proudly took Laguna and his brothers to war movies like John Wayne's 1968 film "The Green Berets," which was a turning point in Laguna's young life.

"He said, 'You know, if I had gotten to stay in the Army, this is what I wanted to be. I wanted to be a Green Beret,'" Laguna said in an interview. "My dad wanted to be a drill sergeant … an airborne guy … a Ranger. … Because my dad couldn't do it, I (wanted) to do it for him."

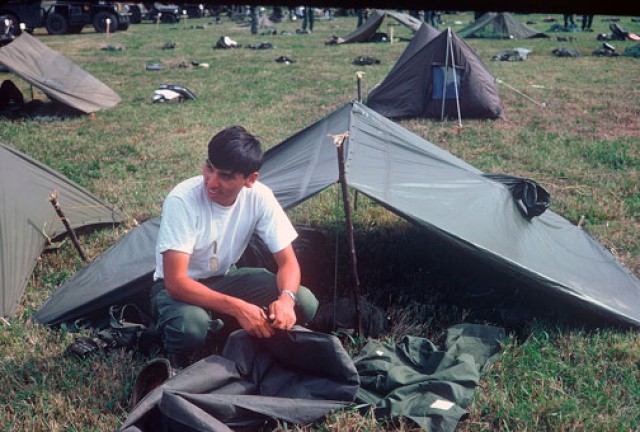

Laguna knew that to become a Green Beret he couldn't just be a good Soldier, he had to be the best. So he finished first on runs, maxed his physical training tests and studied hard. But after three years at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, he received orders to Fort Jackson, S.C. He was going to be a drill sergeant, another of his father's dreams.

His trainees, who in the mid-70s were among the first enlistees into the all-volunteer Army, never forgot him. He was famous for being tough, and for biting the head off a bird -- just the way his Mexican Indian grandfather Merced Santoyo had taught him.

"Early in the mornings we'd go out and catch pheasants or quails … that he would make for breakfast," Laguna explained. "We would run and catch (them) and pick up two or three at a time. You don't want them to run off. You can't let them go, so you bite the head off, set it down and catch more.

"When I was a drill sergeant … I had all these trainees in front of me. We're at a rifle range … and this bird just fell out of the sky next to me, flopping its wings. I picked it up and bit its head off without thinking, and then … I heard these helmets hitting the ground. It was my trainees passing out.

"I gave some survival classes and showed them how to kill and skin rabbits by biting a hole in the back of a rabbit's neck and ripping it off. … I was just teaching them how I was raised as a Native American. You don't waste anything and you don't have a lot of tools," Laguna continued.

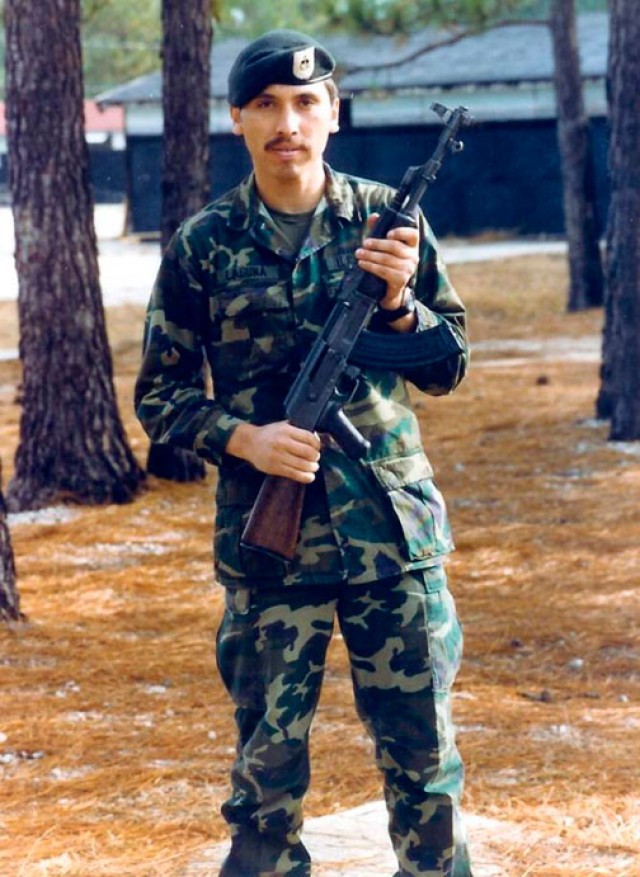

They were survival skills that served him well when he finally did become a Green Beret in 1978. That green beret, which he promptly presented to his father, symbolized "the culmination of years of dreams and effort." Of 250 Soldiers in his class, 30 had graduated. "It's a test of fortitude. … You weed out the ones who want to go there just to wear the beret."

Later, as an instructor at the Special Forces school, Laguna not only headed the survival committee, he helped former prisoner of war Col. Nick Rowe -- famous for escaping the North Vietnamese after five years of captivity -- develop Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape training requirements that are still in use today.

"I think one of the most important survival skills … you need to know is what you can handle, what your body can withstand as far as being deprived of food and water, mental and physical (stress)," Laguna said. "That's one of our greatest survival skills. That's why we put that SERE program together, because it teaches a person how far he can go before he … breaks down.

"I tried to (teach) the 'don't give up' attitude. … What I try to instill in all of the students I've taught is 'You can go further than you think you can. You can do more than you think you can.' It's all mental."

An "If-you-can-do-it, I-can-do-it" bet with his brother Art, a pilot and eventually a chief warrant officer 5 in the California National Guard, landed Laguna in flight school with only two weeks' notice. Then Laguna joined the brand-new 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Night Stalkers), where he spent the rest of his career.

"We (got) to go a lot of places, do a lot of neat things, either training or real-world missions," Laguna remembered. "Obviously a lot of them we can't talk about, but … my career was very rewarding. … That's probably at the sacrifice of my family … but I had 100-percent support from my wife."

It was especially hard on his wife, Deonna, and kids when Laguna deployed to Iraq during Desert Storm. He wasn't "officially" there, so Deonna had to say he was at a "training exercise" while other families displayed yellow ribbons.

And it was hard, after surviving numerous covert missions deep into Iraq and a friendly bomb, as well as a mysterious, painful rash that may or may not have been Gulf War Syndrome, to return to ribbing from his buddies: "Man Dan, it's too bad you missed it. You wouldn't believe the kinds of things we did. You should have been there!"

There was no debate about Laguna's next deployment, however. He joined the search for his fellow 160th SOAR pilot and friend, then-Chief Warrant Officer 3 Michael Durant, who had been captured in the Black Hawk Down incident in Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1993. Eighteen Americans were killed and Durant was released about a week later, but Laguna was done. A mortar had hit a spot where he was standing only moments before, injuring two senior commanders and several other Soldiers on the very day he arrived. There had been "too many close calls," and it was time to retire.

Or so he thought.

Haiti began to heat up when Laguna was on terminal leave in the summer of 1994, and the Army was short a helicopter flight lead for Operation Uphold Democracy.

"Tell them I'll go," Laguna told his boss.

"I already did," his boss answered.

But Laguna never made it.

During a nighttime training flight that July, his helicopter's engine "hiccupped, quit." It crashed with about eight times the force of gravity and bounced, end over end -- high enough to clear a 15-foot tree -- for about 300 feet before landing on its right side in a ball of fire.

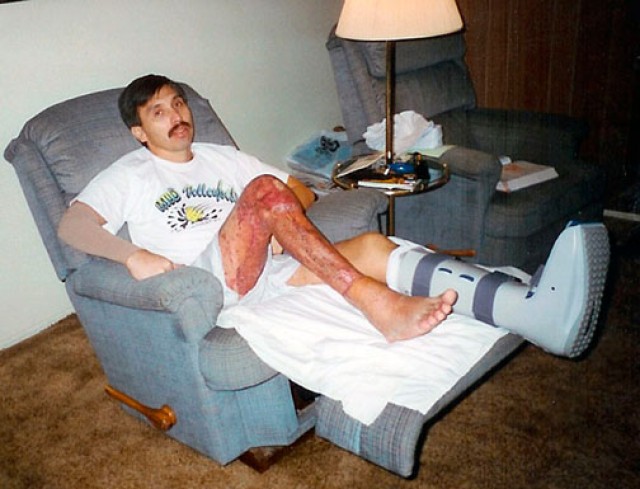

Strapped to his seat, he heard cracking that turned out to be his bones. In addition to sustaining third- and fourth-degree burns, Laguna had broken many bones, including both legs and several ribs that had punctured both lungs.

Something told him to unbuckle his seatbelt, and Laguna suddenly found himself on the ground 20 feet away from the helicopter -- a mystery the investigating board could never explain.

He heard his best friend and copilot, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Carlos Guerrero, screaming, but was too badly injured to crawl more than a few feet. Later, in the hospital, Laguna would scream for his friend after each of his dozens of surgeries. He eventually refused morphine too, believing the intense pain was a just punishment for letting Guerrero die.

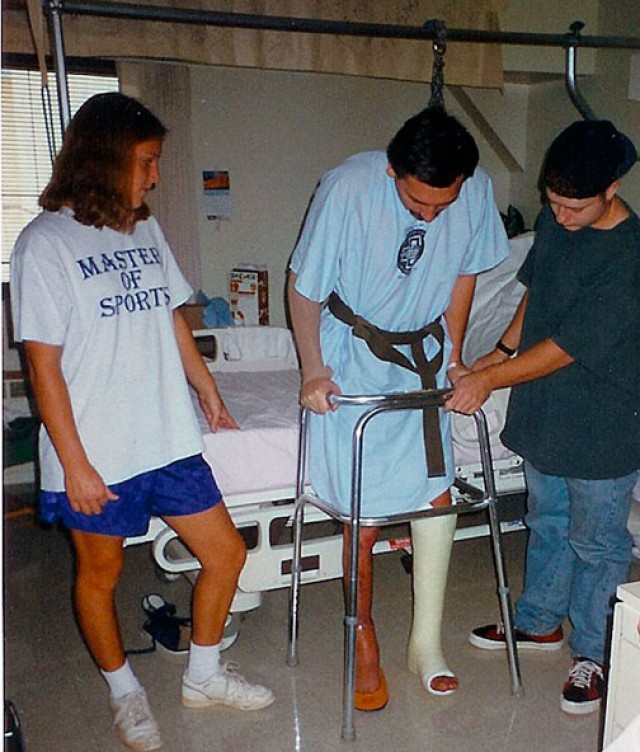

Doctors expected Laguna to die as well, and later told him he would never walk again. Laguna, however, was determined to not only walk, but also run and fly helicopters again. Retirement was the last thing he wanted.

Through sheer determination and by spending eight hours in physical therapy for every half hour the doctor ordered, Laguna was back in the air about four months after his crash and back to duty a year later, even deploying to Bosnia (another assignment he can't talk about).

"I would not have been able to go back to duty in the regular Army," he explained. "Because I was in special operations, those guys look at things differently. … They said, 'When the time comes, you're going to have an evaluation … to see if you can perform your duties.' I worked extremely hard for a year. … I maxed my PT test again, and I did all the evaluations … that I had to do. I'm not saying without pain, without some question in my own mind about whether I was going to be able to do some of those very demanding things … without much of a leg … but I did it. It was just like Christmas.

"It goes back to (my motto): 'You've got to live hard to be hard.' People will say if you fall off your horse, get back on. … You can't let it beat you. … Every guy who's been in the task force for any length of time … has crashed. … There's two guys who are very close friends of mine -- after their crash, they quit flying. I couldn't do that. I won't quit."

Laguna eventually did retire in 2001, but was back in the action by 2004, signing on to work as a contractor flight lead in Iraq. Laguna survived another helicopter crash and his brother Art was killed practically in front of his eyes, Jan. 23, 2007, in an insurgent attack that was so violent, so intense, Laguna had never seen anything like it, even after decades in special operations.

"It felt as if all the blood ran right out of my body and my eyes began to fill with tears," Laguna wrote of cradling his brother's body in his arms. "Tears trickled down my face as I whispered, 'I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I love you Art. Please forgive me.'

"I'm the one who should have died in Iraq instead of my brother, who was working for me," he later added. "My brother should never have been there. … That's the only mission we ever flew together and we both got shot down together."

And then Laguna had to call his mother and his sister-in-law with the news. It was the hardest thing he ever had to do. "I'd rather get burned again," he said. He stayed in Iraq until his company sent a replacement and then returned two weeks after Art's funeral. His men needed him.

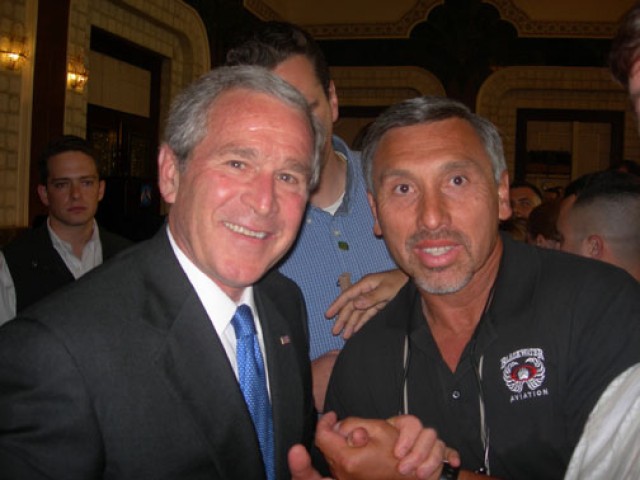

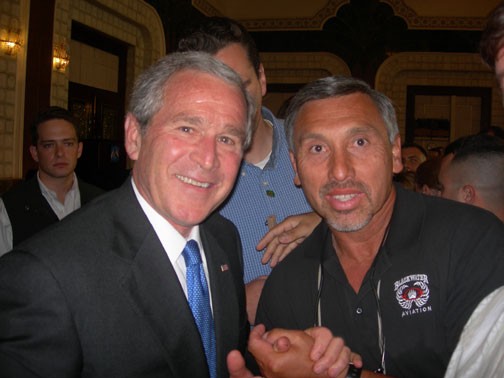

Today, Laguna advises His Majesty King Abdulla II of Jordan on all aviation matters. He's briefed senators, ambassadors and presidents -- not bad for a dirt-poor "guy from Rio Linda, Calif., who couldn't amount to anything."

Social Sharing