Most teenagers spend their summers working, hanging out with their friends and grumbling about reading assigned for the coming school year. Very few would voluntarily give up a chunk of their vacations to study World War II history, and fewer still would do it eagerly, but that's what is special about the students participating in National History Day's Albert H. Small Student and Teacher Summer Institute, "Normandy: Sacrifice for Freedom." They want to learn about history.

Fifteen students from around the country, each accompanied by a teacher, participated in the summer program, visiting the nation's capital and Normandy, France, to conduct research on specific American Soldiers. Students selected servicemembers from their hometowns to study, making the project more personal.

"The goal is, one, to remember D-Day," Ann Claunch, director of curriculum for NHD, said. "This is to bring (out) the reality of what was sacrificed and the stories behind the Soldiers."

National History Day is a yearlong academic organization for secondary and elementary school students, where the students choose historical topics related to a theme and conduct primary and secondary research. Per the NHD website, they perform their research at libraries, museums and archives, in addition to conducting historical interviews and visits to significant sites. The program culminates with a national competition each June at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The Summer Institute is a professional development program within NHD that is usually reserved just for teachers, but this year it was opened as a prototype for students and teachers as co-learners, Claunch explained.

"As far as I know, it's the only one in the country," she said.

The institute kicked off June 18 in Washington, where the students listened to a series of lectures on World War II, including a keynote address by one of the beach masters at Omaha. June 20, four students selected by lottery laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns in Arlington National Cemetery to honor fallen servicemen and women.

It was a sweltering afternoon, but Amanda Hoskins, Joshuah Campbell, Civil Air Patrol Cadet Airman 1st Class Katelyn Davis and Jeremiah Tate wore dress clothes. The students descended the stairs from the back of the amphitheater amid a crowd of onlookers and fellow program participants to maneuver a wreath of white flowers into place at the foot of the tomb.

Davis explained the wreath was to honor Soldiers who fell during the D-Day invasion, as well as the unknowns buried in the tomb.

"It's a beautiful thing to experience the history of the United States in its rawest form, in the nation's capital, so I've been enjoying it so far," Campbell added. Though this was his fourth year participating in the regular NHD program and contest, he had never seen the changing of the guard before, let alone been part of a wreath ceremony. He said being part of that ceremony was an honor in itself.

Cathy Gorn, executive director of NHD, described the students as poised and respectful during the ceremony, adding that the NHD program and Summer Institute are dedicated to helping people understand how history has shaped today's society and how the lessons history teaches can help people make better decisions in the future.

"It's about good citizenship," she said. "If you don't know your history, then democracy could be in trouble."

After a few more classes and a visit to the National Archives to complete some research, the students in the Summer Institute departed for France, where they stayed until June 28, touring Paris and the surrounding areas.

They visited several historical sites, including the Pegasus Bridge in Benouville; Pointe du Hoc, a German clifftop casemate situated between Utah and Omaha beaches; Utah and Omaha beaches themselves; and the Normandy American Cemetery.

Davis, a World War II enthusiast from Freeland, Md., who read several books about that era of history before her project, said visiting the sites brought the events home for her. She chose to study Capt. Edward Peters of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

"You can look at the numbers and it's one thing, but when you go there and you see the guys in the cemetery and you see the beaches, it finally just … it brings a personal story and a personal side to it that you wouldn't have if you had just read the books," she said.

During her research, Davis discovered Peters destroyed a machine gun post after landing in Normandy. "I actually got to see the field where he died. It was a huge gap, the fact that he took that out by himself is amazing," she said.

Indianapolis native Tate studied Maj. J.W. Vaughn of the 502nd Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. Tate wanted to know exactly how Vaughn died, and learned at the National Archives that while Vaughn was securing wagons, German forces ambushed the Soldier on the side of the road near Pegasus Bridge. He managed to eliminate two enemy soldiers before he was killed.

Vaughn landed close to Omaha beach, and when Tate and the other students visited Pointe du Hoc, he was impressed with the view, and the historical implications.

"That was the first time I had ever (seen) a beach, and it was major. They had a few bunkers there where the Germans could look out at the ocean and it was between the Utah beaches and the Omaha beaches," Tate said. "They had a wide view of what was coming in and I felt like we were at a disadvantage when the Soldiers were coming in from America. It was a very emotional experience."

"When we're actually standing there, where these Soldiers were standing, seeing where these battles took place, you really have a completely different understanding," Hoskins agreed. "You kind of feel what the Soldiers were feeling."

Hoskins, who hails from Rhode Island, studied two Soldiers: 1st Sgt. Henry S. Golas, 2nd Ranger Battalion, and Pvt. Michael Macera, 41st Infantry Division.

Golas landed near Point du Hoc on Omaha beach. "It was really amazing to see where he started in the water and how far he had to get to the point where he actually died," Hoskins said.

The Soldiers landed during low tide, Hoskins explained, and the Germans had put so many obstacles on the beach and in the water that the boats couldn't come up very far. Golas had almost reached the grass when he died. Before the trip, Hoskins knew little about Golas family -- she found out he was married shortly after she returned from France.

"It makes me so thankful for the sacrifice all these Soldiers made for our country. It was just incredible to be there," she said.

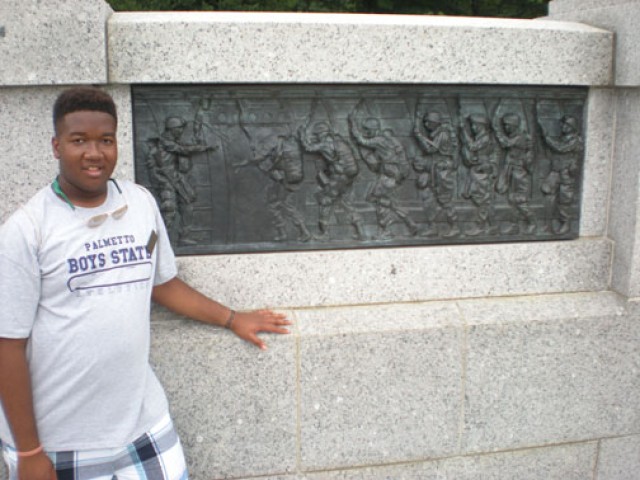

"You get to an understanding that these are real young men, some of them not much older than myself," Campbell agreed. Soon to be 17, he studied 1st Lt. William Gaillard of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division.

"I wasn't really interested in war history in general before this trip, but you know, it's changed my perspective. It's made me appreciate war history more and how much it contributes to our history in general," he said.

The students read eulogies while visiting the Normandy American Cemetery, which was an emotionally charged experience. Tate, Campbell, Hoskins and Davis all felt as though they had bonded closely with the Soldiers they chose to study because of the extensive research and the shared experience of being on a foreign shore.

Hoskins will help her teacher and chaperone Lisa Johansen teach high school juniors about World War II and the D-Day invasion this year. She believes that her ability to connect with other students will help her provide an easily understood perspective of history.

"Most of the men on D-Day knew that they weren't going to survive," Hoskins said. "And to go into it like that, it just really amazes me. I want everyone to be able to feel like that, even if they can't go there and stand on the beaches. They should really understand the sacrifice these men gave."

Davis believes her life would be completely different if it wasn't for the Soldiers fighting in World War II, and she encourages other students to look at history from different angles. She added that students not interested in war history should look up the historical context of the things they do like, such as music or art, and discover how they tie in with other parts of history.

"It will just open doors for them," she said.

"We're the legacy of all the history that has happened before," Campbell said. "While we may think it's boring, we still have to appreciate it for what it is."

EDITOR'S NOTE: For more information on National History Day and the Summer Institute, visit http://www.nhd.org/normandyinstitute.htm.

Social Sharing