FORT DRUM, N.Y. -- What began as a four-month exercise to prepare Soldiers for a potential arctic war, resulted in a historic blaze that took the lives of five World War II veterans.

In 1947, Exercise Snowdrop was the largest over-snow airborne maneuver that the U.S Army had embarked on at the time. The training was part of a series of efforts designed to determine effective equipment, logistics and tactics for fighting in a sub-zero environment.

The training, held at what was once Pine Camp, began Nov. 1, 1947, and carried through until February, but not all of the team members saw the exercise through until the end.

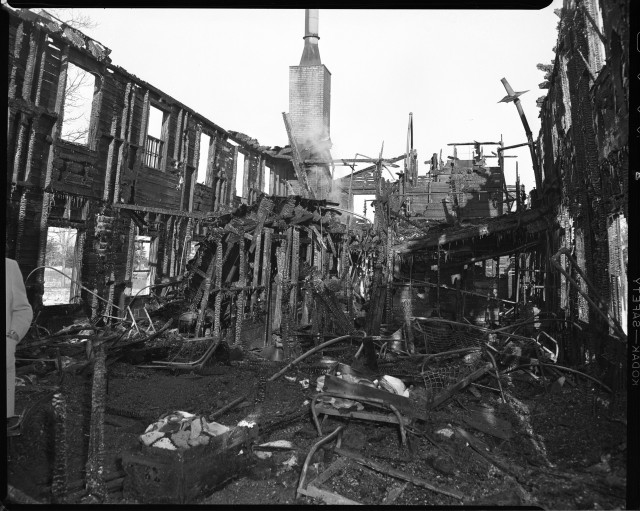

In the early morning hours of Dec. 10, 1947, officers housed in Bldg. T-2278, a two-story wooden barracks, were awakened by smoke and shouts coming from the hall on the second floor.

The shouts belonged to Capt. Frank Turner, who had been woken by a fire that erupted in their quarters at about 2:30 a.m.

It is believed that after Turner ran through the building, warning his fellow Soldiers of the fire, he jumped from a window, hoping to make it to safety. Through a twist of fate, as Turner was exiting the window, his wedding ring caught on a nail or piece of debris.

Ironically, a symbol of union between him and his wife became a union between him and the building. Turner suffered from severe burns -- nearly 90 percent of his body had suffered third-degree burns.

The fire resulted in five casualties, including Turner, who died 18 days later.

It was reported that two, out of the believed 11 Soldiers who escaped, had to be restrained from re-entering the burning building to save their comrades.

A delayed response

The fire department at the time was manned by Soldiers, and it was located in a building near the barracks, on Division Hill -- the original headquarters area for the installation.

It took the fire department about 45 minutes to respond to the fire, according to Duane Quates, an archeologist with Fort Drum's Cultural Resources Branch.

In his report, the fire chief stated that two-thirds of his personnel had been firefighters for less than three months and that the blaze was a "flash-fire," which is considered a very intense fire.

"We know there was a fire watchman going from building to building … and he came out of one building and saw the (flames) coming out of the second-story windows (of Bldg. T-2278)," Quates said. "The building was already engulfed … when he spotted the flames."

Three hours, three fire engines and 1,950 feet of water line later, firefighters finally extinguished the blaze, according to the daily fire log.

Although many barracks buildings were occupied at Pine Camp during the time of the fire, it is believed that the fire got its start in that particular building because of a faulty boiler, but that is only one speculation, Quates noted. Another potential cause of the fire was a lighted cigarette.

Killed in the fire that night were Capt. Robert Dodge and Lts. Robert Manly, Wallace Swilley and Rudolph Feres.

Later reports noted five officers suffered varying degree burns, among other injuries. A private with the fire department also suffered from smoke inhalation.

All of the men were treated at various hospitals and released, except for Turner, who died with his wife and mother by his side.

Besides one other officer, the names of the remaining, unharmed Soldiers are unknown.

The location of the Army's original fire report is unknown, but it is possible it was sent to Army Headquarters after the fire, Quates explained.

"It's possible (the file) was sent to St. Louis (Mo.) and burned up in that fire, but we can't say -- it's all speculation from this point," he said. The fire he refers to is the 1973 blaze at the National Personnel Records Center, which destroyed up to 18 million military personnel files.

"The fact that we can't find (these records) leaves open (a lot of) questions," Quates said.

Historic lessons learned

"This fire is the only structural fire on Fort Drum that had fatalities. Every other structural fire may have had injuries, but they never had fatalities," he said.

Quates said he believes this is because the fire chief's report noted recommendations after the fire, many of which have been implemented at Fort Drum, as well as Armywide.

The fire chief recommended implementing safety precautions, such as using self-closing doors on stairways leading from first to second floors, installing a permanent escape ladder, and installing a heat raiser alarm, which would ring a bell to warn occupants as soon as a fire starts.

"Those things were not implemented in 1947. They weren't standard for building construction," he said.

Fire extinguishers were the only fire protection equipment listed on the building's real property record.

Quates noted that because they don't have the Military Board of Inquiry's official report, they cannot directly link the barracks fire to fire code changes, but fire suppression and alarm systems were incorporated into the planning and design of the next round of construction on post, which began in 1950.

Making history

On Aug. 19, 1948, four widows of the fallen Soldiers sued the United States, claiming their husbands' deaths were the result of negligence due to a faulty heater. The cases were dismissed by a Northern New York District Court judge, stating the government was not liable for injuries military members sustained while on active duty, under the Federal Tort Claims Act.

The following year, Bernice Feres, widow of Lt. Rudolph Feres, brought her case before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. The court dismissed the case that fall.

Almost exactly a year later, in 1950, Feres appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, who sided with the earlier courts, and the case was dismissed.

Those actions led to what is now known as the Feres Doctrine, which prevents active-duty military personnel from collecting damages for personal injuries sustained while on duty and prohibits Family Members from filing wrongful death suits when a service member is killed.

The Feres Doctrine continues to be challenged more than 60 years later.

"That doctrine started here (Fort Drum), basically because of the (1947 barracks) fire," Quates noted. "It's basically where the relationship of the Soldier to the government was defined."

Digging into history

Years after her own children were grown, Elizabeth Barbee, Turner's oldest daughter, decided to write to her congressman with the intention of obtaining her father's records and an official copy of the cause of the fire. She was told her father's records had been destroyed during the fire at National Personnel Records Center in 1973.

She didn't give up there, and a few years later she wrote to the Watertown Daily Times, requesting copies of the barracks fire story.

"I was appalled by the pictures," Barbee said. "How anyone survived that fire in that wooden building is beyond me."

Quates said they were unaware of the event until Turner's daughters, Carolyn Leps and Elizabeth Barbee requested to visit the site where the barracks fire occured.

While on a cross-country venture last year, Leps and her husband, Paul, decided to stop at Fort Drum and see where her father died.

"I wasn't looking for this," Leps said. "I was just wanted to see where the fire happened."

Equipped with information gathered by her middle sister, Anne Marie Fletcher, who had died eight years earlier, along with newspaper clippings saved by her mother, photos and other documents, Leps began a journey that would bring a new piece of information to add to Fort Drum's history book.

The Lepses met with Quates, and he took the couple to the site, which is now a bare spot between two barracks buildings.

"We get multiple requests throughout the year to take people to various sites. This was the first time I have taken anyone to the site where somebody had died," Quates said.

Although there is nothing visible above ground, he noted there is a possibility there are remnants below ground.

"This was, in my mind, something sacred. It's hallowed ground -- somebody had died there," Quates said.

The trio poured over maps, building blueprints and records, and began revisiting and piecing together an event that, months earlier, was unknown to many Fort Drum personnel.

When Leps began telling him about the Feres Doctrine, Quates said he realized the historical importance of the site.

"It had broader implications for the entire … military," he added.

In November, Barbee and a friend traveled to Fort Drum and met with Quates, who took the visitors to the site where the old buildings still stand, except for that one lone empty space that was occupied by Bldg. T-2278.

"It was so eerie, (and) so very quiet," Barbee explained. "Maybe it was the pictures from the newspaper in my mind, but I felt I could hear the men screaming while trying to get out the windows; some jumping to their deaths (and) some never making it out of their beds."

Last year, a team from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, Construction Engineering Research Laboratory began researching the fire. Their report led to the publication of a 44-page book, "1947 Barracks Fire, Pine Camp (Fort Drum), NY," about the events surrounding the blaze.

Quates said he hopes to see the fire, its victims and Turner's heroic actions memorialized with a historic marker at the site.

"(A historic marker) is the best way to remember a site, especially after something is totally gone," he explained.

Affecting a Family

After Turner's death, his wife was given a job in Washington, D.C. Turner's daughter Carolyn was sent to live with her maternal grandparents until she was 6 years old, and 4-year-old Elizabeth and 3-year-old Anne Marie went to live with their paternal grandparents.

Decades later, to learn that Army officials wish to remember the events that claimed their father's life, drew a reaction from the sisters.

"It never even crossed my mind that anybody would care after 60 years," Leps said. "It's kind of overwhelming to me. It gives me such a feeling of joy (and) happiness, because … I didn't think anybody would have cared."

Barbee said that although she has searched records at the National Archives and the Supreme Court, written, emailed and phoned over the years, she never did it to find "closure."

"My search has always been to find an 'official cause of the fire,'" she added.

"My father was always a picture on the wall," Leps said. "I never knew my father. I read the story, and I've heard my mother talk about it. My first thought of when I die is 'I'll get to meet my father.'"

"I didn't expect this to start out to be a major project. It turned out I realized that this is something that needed to be documented," Quates said.

Social Sharing