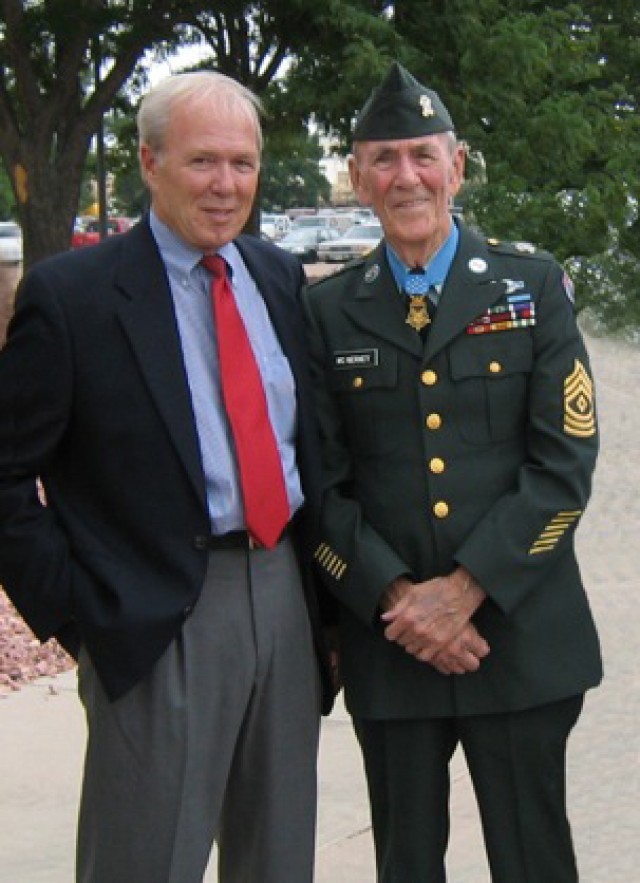

FORT CARSON, Colo. -- Editor's note: 1st Sgt. David H. McNerney's heroic actions during the Vietnam War earned him the Medal of Honor, which will be given to the 4th Infantry Division in a ceremony Oct. 6. McNerney, the last living "Ivy" Division recipient, died of lung cancer in 2010. His lifelong friend and brother in arms, Rick Sauer, recalls how he met McNerney and the March 22, 1967, battle that earned him the medal.

Rick Sauer sat on the porch of his home in Lone Tree, Colo., smoking a Don Pablo cigar. The grizzled Army pilot, more gray and wrinkled in his retired years, looked out at his manicured lawn, pausing between puffs to watch the sky when a plane flew overhead.

"That's an F-16," Sauer said, cupping his hand over his eyes to shield the sun as he gazed at the fighter jet, his words drowned by the roar of the plane.

Inside his home, models of airplanes lined the bookshelves of Sauer's impeccably clean office. On the walls, certificates of achievement and pictures from his military days surrounded the retired lieutenant colonel with memories. By the door, a portrait of another Soldier hung -- 1st Sgt. David H. McNerney.

"I called him 1st Sgt. McNerney till the day he died," Sauer said.

Despite their 45-year friendship, the two always referred to each other by their formal titles.

"He never called me by my name. He called me by my rank -- if it was lieutenant, captain, major, colonel. He always called me Capt. Sauer, Maj. Sauer, and that's the way we were," Sauer said. "We always kept that. And we were comfortable with that. We were Soldiers together until the end."

McNerney died in October after a nine-month battle with lung cancer. Before he died, he asked Sauer to deliver his eulogy.

"He told me to keep it short and simple," Sauer said. "(He said) 'Just tell them I was just doing my job.'"

Throughout his 20-year career, Sauer said he remained close friends with the man he credits with making him a better leader and Soldier.

"He was kind of a hard guy," Sauer said. "He looked tough. He looked serious. But he looked professional."

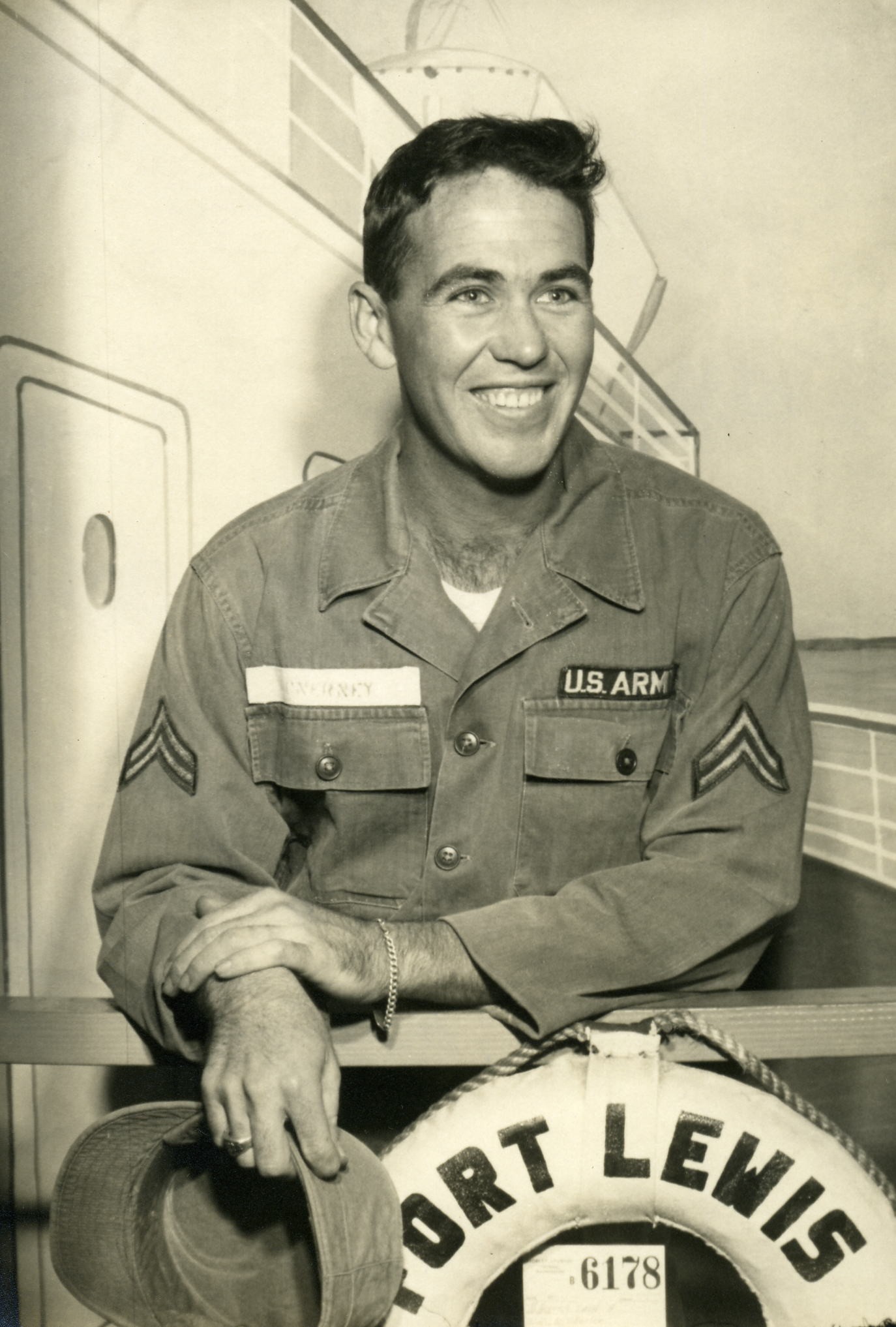

A first lieutenant in March of 1966, Sauer was impressed with McNerney who was 15 years older than the new officer and had already served two combat tours in Korea with the Navy before joining the Army.

Sauer said McNerney was strict and demanded the best of the Soldiers of Company A, 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division.

"He was hard, but he was fair," Sauer said. "He didn't play favorites at all. … He never let up on them. And they didn't like him. They really didn't like him. It wasn't until Vietnam that they really understood."

Sauer recalled a time when a Soldier was beaten outside the barracks and McNerney found out no Company A Soldiers came to help.

"The first sergeant called a formation and he just chewed everybody out," Sauer said. "He said, 'Nobody, nobody ever attacks anybody in A Company. And if it ever happens again, every one of you better be out of that barracks and be out there defending him. I never want to see a man in A Company alone.'

"And they got the word. They're in this together."

In October 1966, after almost a year of training together, the Soldiers of Company A deployed to Vietnam.

After a few months in country, Sauer said Company A moved to the central highlands during the Tet holidays, the Vietnamese lunar New Year's festival.

On March 22, 1967, Company A slept in the jungles near Polei Doc, later named "The Valley of Tears."

"(That) morning we started to break camp," Sauer said, his cigar going cold. "It was really eerie. You didn't hear the jungle noises as you did before. We broke camp and moved out about 7-7:30 (a.m.) and fifteen minutes later, we were engaged and all hell broke loose."

Sauer said a North Vietnamese army battalion attacked the 108 men of Company A, attempting to divide the company in half with McNerney up front and Sauer in back.

"While the battle was going on, A Company kind of got split. The A Company commander and a forward observer, they were both killed. So the first sergeant took over (up front)."

Enemy forces killed all but one officer, leaving 1st Lt. Sauer as the highest ranking Soldier in the company.

"I tried to link up so I took one of my squad leaders and we went up to link up again, because if we didn't, they had us almost in half, we were going to be overrun," Sauer said. "They were just coming. They were in the trees. They were tied into the trees with their weapons tied to them so they wouldn't drop them."

Sauer suffered gunshot wounds that broke his leg. Shrapnel ripped through his other foot, leaving him immobilized on the jungle floor.

"I couldn't walk, I couldn't crawl," he said. "I was calling in the artillery air strikes. But pretty soon, I really became ineffective. I couldn't do it anymore. I was bleeding and kind of going in and out a little bit. At that point, the first sergeant took over command of the company."

McNerney took charge, despite being blown from his feet by a grenade. Sauer said McNerney ran through the battlefield, exposing himself to enemy fire, to stop a machine-gunner who was slaughtering the company.

"He went out there and destroyed that machine gun by himself," Sauer said.

Support troops tried to locate the ongoing battle, but the thick jungle made it nearly impossible.

"We were in triple canopy jungle," Sauer said. "Nobody could get to us, nobody could see us. All the (smoke from the artillery) would drift underneath the jungle top and maybe drift off hundreds of yards away. So … you can't say where the smoke is."

McNerney climbed to the tops of the trees to string an identification panel across the canopy, realizing air support could not locate Company A.

"He was under fire when he did it," Sauer said. "His performance was extraordinary. His bravery, his selflessness, his complete disregard for his own safety."

McNerney requested chainsaws, grenades and fuel so the Soldiers could clear a landing zone to evacuate casualties.

The men of Company A fought for more than eight hours. One Soldier propped Sauer against a tree so he could continue shooting.

"By that point we were fighting for each other. We were fighting to live. Everything (McNerney) taught them, just clicked. They fought for each other. A lot of them did just unbelievable things. They were all heroes that day. No one thought of themselves."

Of the 108 men in Company A, 22 were killed, 43 wounded and 43 marched on the next day, Sauer said.

"Some people probably thought that was the end," he said. "That's just normal. But nobody ever gave up. Nobody ever had the thought that I'm not going to fight anymore. Nobody ever thought they'd give up defending their fellow Soldiers."

After the battle, Sauer said Company A found 130 bodies and more than 400 graves dug by North Vietnamese forces for casualties.

"Horrific carnage that day on both sides," he said.

Miles from the ongoing battle, Soldiers of Company B attempted to reach Company A.

"They marched and fought to get to us all day. There were so many men dead, so many men wounded, so many men bleeding, people hadn't eaten all day and we were running low on ammunition. It appeared that (the North Vietnamese army) was regrouping and coming at us again. Had it not been for B Company, none of us would have survived."

Sauer also credits helicopter pilot Don Rawlinson, a chief warrant officer, with saving lives.

"He came and flew out the wounded. He risked his life multiple times. … The back of his Huey helicopter was just flowing in blood from continually taking out the wounded people. He did quite a job."

Rawlinson evacuated Sauer, leaving McNerney and Soldiers from companies A and B behind for the night.

Despite his injuries, McNerney refused to evacuate until a replacement arrived the following day. After being evacuated from the battlefield, Sauer was sent to Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii. On his rest and relaxation time from Vietnam, McNerney visited the lieutenant.

"He walked into my room and he said, 'Lieutenant, how long are you going to lay here before you come back?'" Sauer said. "I was in traction. I had IVs in me. I'd had three surgeries already. … That's the way he was."

After the battle in the Valley of Tears, Soldiers in Company A received numerous awards, including 25 Bronze Star Medals and 65 Purple Hearts.

Army officials submitted McNerney for the nation's highest military decoration. On Sept. 19, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded the Medal of Honor to McNerney at a ceremony held at the White House.

Sauer missed the ceremony.

"I got hit in the face with a racquetball racket the day before," he said. "I wasn't there. I was blind. I couldn't see."

Since that ceremony, Sauer has not missed a reunion with McNerney and the men of Company A.

In 2010, McNerney, Sauer and the Soldiers from Company A visited the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. McNerney had been diagnosed with lung cancer and had to use a wheelchair.

"We formed up the company in two columns," Sauer said. "He and I were in the front of each column and I gave the command, 'Forward, march.' And he was in his wheelchair and we walked down the wall. People just parted for us."

At Panel 22E, Company A stopped to view the names of the 22 men killed in action in the Valley of Tears.

"Fifty feet before we got to the panel, (McNerney) asked that we stop and he got up and he walked the rest of the way," Sauer said.

Sauer and McNerney laid a wreath at the panel as the company saluted its fallen comrades. Afterwards, McNerney had to sit back in his wheelchair.

Three months later at a dedication ceremony at American Legion Post 658 in Crosby, Texas, McNerney had to rely on supplemental oxygen.

"He was embarrassed, he didn't want to (use the oxygen)," Sauer said. "He didn't want his men to see him wearing oxygen."

After the ceremony, McNerney refused to leave until every member of the audience left.

"He sat there in his chair and shook every hand, took every picture and signed every autograph requested," Sauer said. "After that he got really sick. But that was his duty."

McNerney died Oct. 10, bequeathing his Medal of Honor to the Soldiers of the 4th Infantry Division. A year after his death, McNerney's Soldiers will return to Fort Carson to formally turn his medal over to current Soldiers of the "Ivy" Division.

"He loved being a Soldier and he loved the United States Army," Sauer said. "He spoke not of him receiving the Medal of Honor, he spoke of A Company receiving (it) and he deflected so many honors and accolades to A Company. ... He would never say he loved them. But he did. He had no children and these men became his sons. He would do anything for them, any day, any time. And when they were together, he was there."

Social Sharing