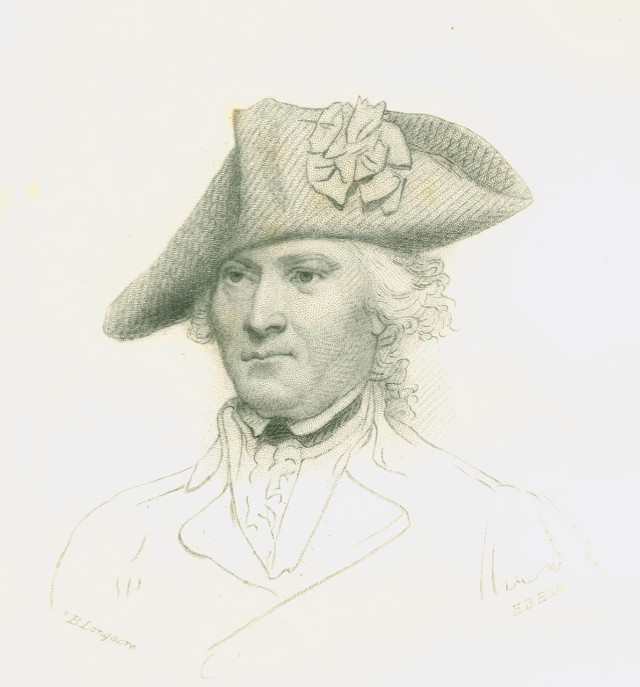

The cold morning of November 4, 1791, found the U.S. Army camped alongside the Wabash River (located in present day Ohio) deep in enemy controlled tribal territory. The Governor of the Northwest Territory, Major General Arthur St. Clair, a veteran general of the American Revolution, commanded an Army of militia, six-month volunteers and regulars. To increase his firepower, St. Clair had an assortment of eight medium- and- light field artillery pieces. Opposing him was a native confederation army of Miami, Shawnees, and Delaware, under Little Turtle (Michikinikwa), Military Chief of the Miami tribe, led hoping St. Clair planned to march his Army north through the wilderness from Fort Washington (today's Cincinnati, Ohio), the main U. S. Army stronghold on the frontier, to a major native settlement called Kekionga, (today's Fort Wayne, Indiana).

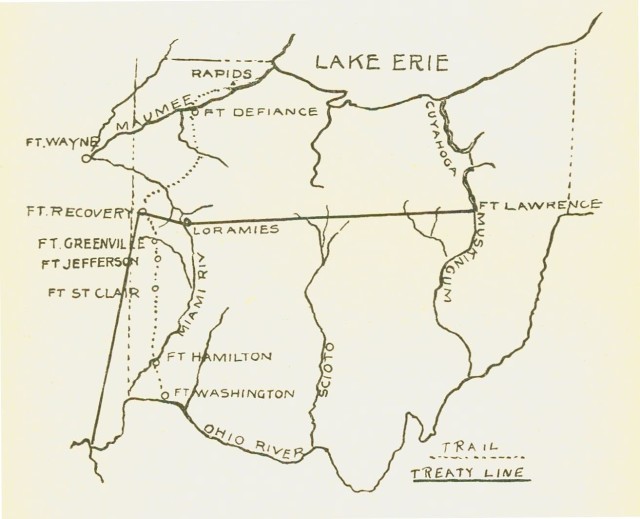

St. Clair's Army was not the first American Army to enter the Northwest Territory. During and after the American Revolution, American regulars, militia and volunteer forces had marched into the Northwest Territory but achieved only mixed results, and were unable permanently to defeat the native tribes and their British allies. The Treaty of Paris of 1783 awarded this territory to the new United States. In 1790, Brigadier General Josiah Harmar led a similar mixed force of 1,100 Soldiers to Kekionga. Little Turtle led the confederation of warriors who repelled Harmar's attacks there.

General St. Clair took command of the regulars who survived Harmar's defeat and sought to rebuild by recruiting and resupplying a new larger Army. His Army began the campaign with 2,000 Soldiers, half of the 4,000 originally planned. The Army was accompanied by women camp followers and their children. The start of the campaign was delayed by shortages of quartermaster supplies such as rations and tools an on-going problem that would hinder the progress of the campaign. Throughout the campaign, St. Clair suffered from gout, which caused him debilitating pain that at times left him bedridden.

St. Clair's Army finally started north on September 6, 1791, toward the Kekionga settlement. It was able to cover only one mile on the first day. Even this short march did not go unnoticed by the native confederation, as Little Turtle's spies reported on every movement St. Clair made. After thirty-five miles, the Army stopped to build Fort Hamilton, a supply depot. After leaving a small garrison there, St. Clair's command departed on October 4. He was worried about a possible ambush of his Army, which had twenty Chickasaw native allies who proved to be poor scouts. Thus St. Clair was marching north blindly unaware of his opponent's actions.

He was able to march only some five to eight miles per day. This was due to his Army being forced to cut paths through the wilderness and to build bridges to enable its cannons and baggage train to cross the many streams and ravines. The weather became wet and icy, making the travel, living and fighting conditions for the poorly dressed Soldiers even worse.

Because of the delayed start to the campaign the six-month volunteer enlistments started to expire. These Soldiers received their discharges and returned to Fort Washington. St. Clair's Army was shrinking from both discharges and desertions. On October 14, he commenced building a new fort, about forty-five miles from Fort Hamilton, which was intended to be a second supply outpost (Fort Jefferson). The condition of the Army worsened as rain fell relentlessly and frost spoiled the animals' feed. Shortly thereafter, sixty disgruntled militia Soldiers, who had declared they would stop the next supply convoy heading to St. Clair, deserted. St. Clair was forced to send the 1st Infantry Regiment, three hundred combat experienced regulars, to protect the convoy of rations and to stop further desertions.

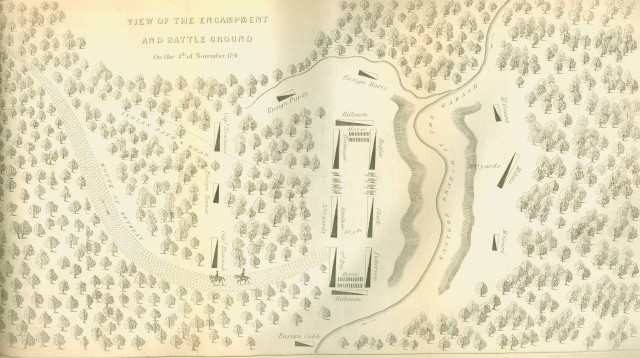

By the evening of November 3, the 1,400 remaining Soldiers set up camps on the Wabash River (today's town of Fort Recovery, Ohio). Dangerously, the camp for the regulars and volunteers was on the opposite bank of the river from the Kentucky militia camp. Even worse, field fortifications were not built, leaving both Soldiers and artillery exposed to enemy fire.

The Army soon made contact with the enemy warriors of the confederacy who had gathered to attack St. Clair. Such warriors were seen outside the camp, and a small formation of Soldiers were sent to engage them. When those Soldiers returned, they reported to Major General Richard Butler, the Army's second in command that they believed the enemy would attack in the morning. General Butler did not convey their message to General St. Clair, who had already gone to bed for the night. Butler also did not order any extra protective measures against an attack.

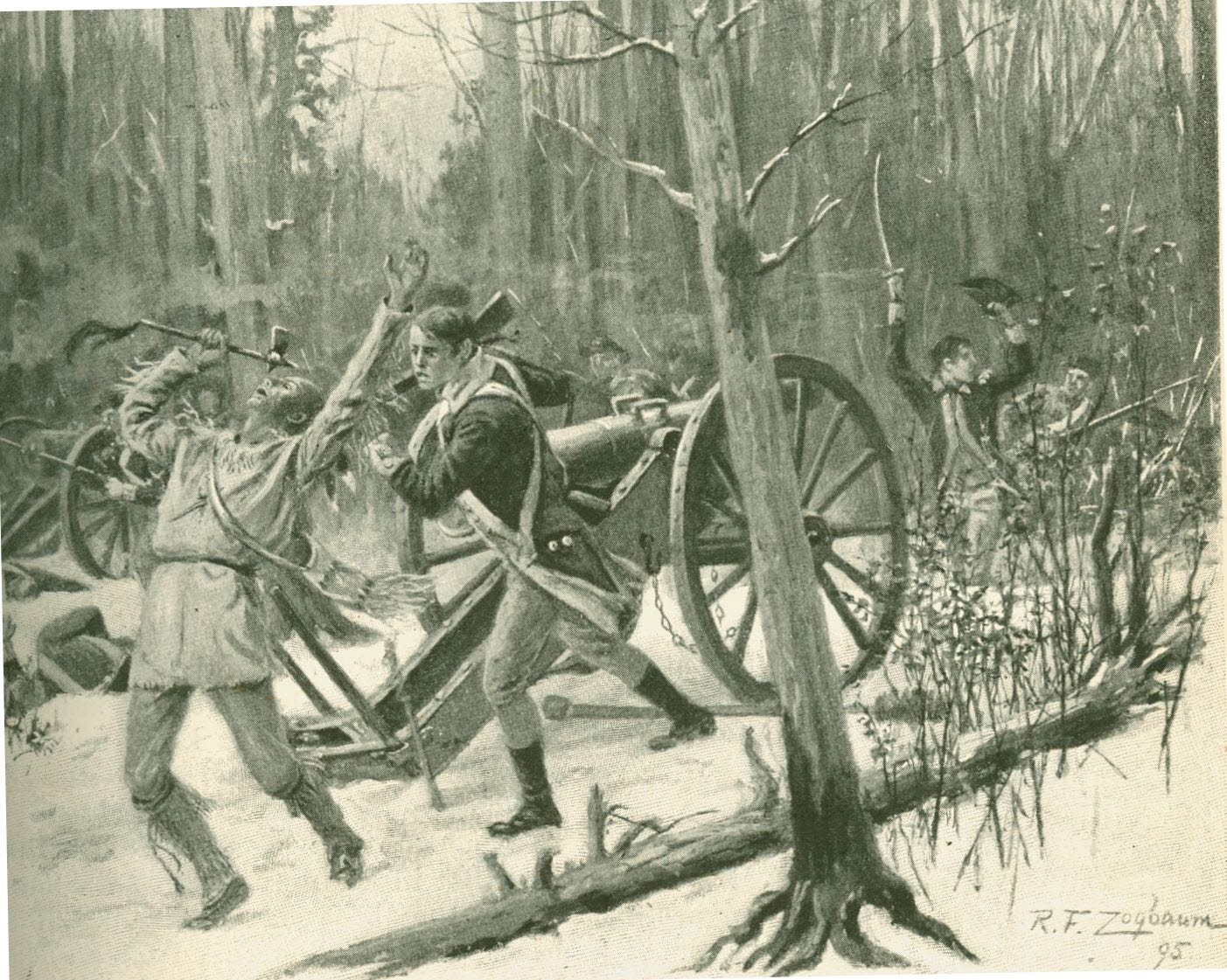

After the Army's reveille on November 4, Chief Little Turtle led over 1,000 warriors of the native confederacy in attacks on the separate camps. The 270 Soldiers from the militia's camp fled quickly, giving little resistance to the attack, and leaving the main encampment of the inexperienced regulars of the 2nd Infantry Regiment to fend for themselves. The artillery's potential firepower was never utilized as artillerymen fell dead around their exposed cannons, cut down by Little Turtle's warriors. The battalions of infantry formed up and commenced firing to defend against the encircling warriors. St. Clair mounted his horse despite his gout. Infantry battalions charged forward with bayonets, hoping to disrupt the native onslaught. As the casualties mounted and the cannons fell silent, the Army's position became grave. After three hours of fighting, St. Clair ordered a retreat to Fort Jefferson. A bold bayonet attack under Colonel William Darke opened a route for those able to escape.

Major General Butler was killed as the main encampment fell to the native warriors. Over 900 Soldiers and their women and children, were killed or wounded with most of those casualties being left behind on both sides of the Wabash. St. Clair would face the nation's first Congressional Special Committee investigation. He was exonerated of any poor conduct before or during his defeat. Secretary of War Henry Knox assessed that the Army was deficient in the number of disciplined troops and had been operating too late into the year. President Washington would select a new general, Revolutionary War hero "Mad" Anthony Wayne, to command an Army that would be trained and drilled into a disciplined force called the Legion of the United States. This new legion corrected the faults of St. Clair's Army.

This new force would eventually demonstrate that the U.S. Army had indeed learned its lessons and implemented the right reforms. Wayne's Legion defeated the confederacy in less than one hour and a half on August 20, 1794, when it assaulted native warriors behind the protection of fallen trees near today's Maumee, Ohio. The Battle of Fallen Timbers was decisive in ending the Miami Campaign and helped establish the U.S. Army's proud heritage of victory.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center, 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021. Website: www.carlisle.army.mil/ahec

Social Sharing