PICATINNY ARSENAL, N.J. (Sept. 1, 2011) -- Amid the chaos and clamor of combat, Army vehicle-top gunners are rightly focused on the gritty imperatives of battle.

Therefore, one wouldn't suppose that they give much thought into how their turret's mechanisms embody a "novel" design because they are such a "technical advance" over "prior art" in a "stream of invention."

Leaving aside legal terms for the moment, no insights are more important than those of combat gunners who understand uniquely how armor position and gun-mount design relate to their dangerous missions.

That is why their insights were incorporated into the 45,000 currently fielded Objective Gunner Protective Kits, according to Thomas Kiel, lead design engineer for the OGPK.

Kiel and his team of engineers from the Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center began work on OGPK in 2005. Their goal was to find a way that allows gunners in Iraq and Afghanistan to fight effectively and see clearly, yet survive threats like small arms fire and the growing threat of improvised explosive devices.

As a starting point, engineers gained unadulterated input by speaking directly with experienced combat Soldiers. They also got inspiration from field-expedient solutions Soldiers developed.

Integrating this real-world feedback, the engineers produced competing prototype solutions and again asked Soldiers to compare them and provide more feedback. The information was assembled and discussed, leading to prototypes that were more refined.

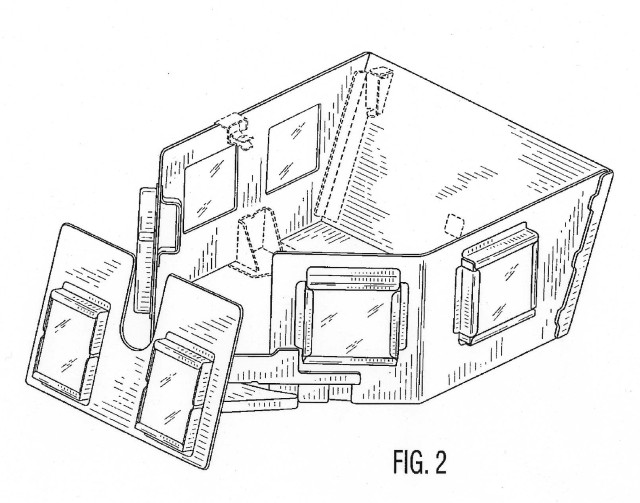

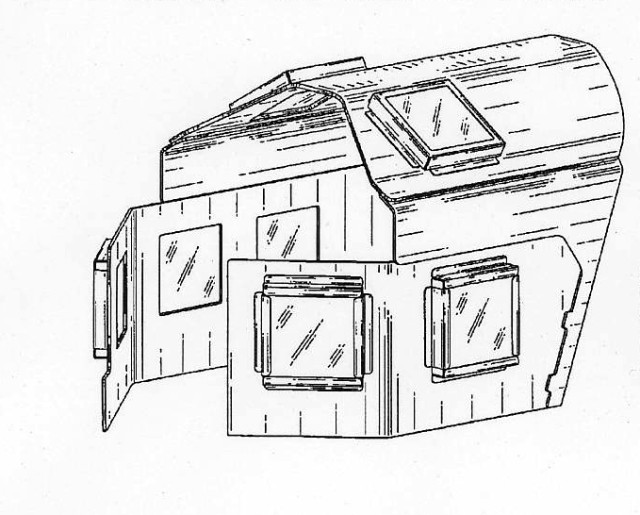

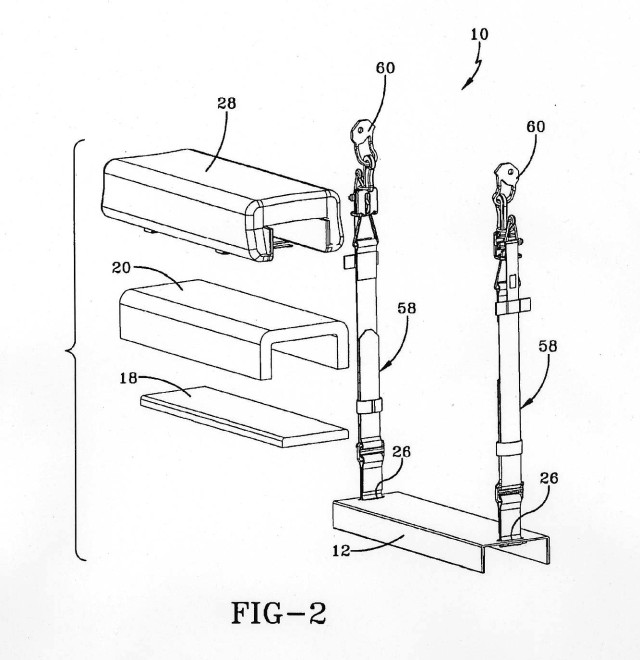

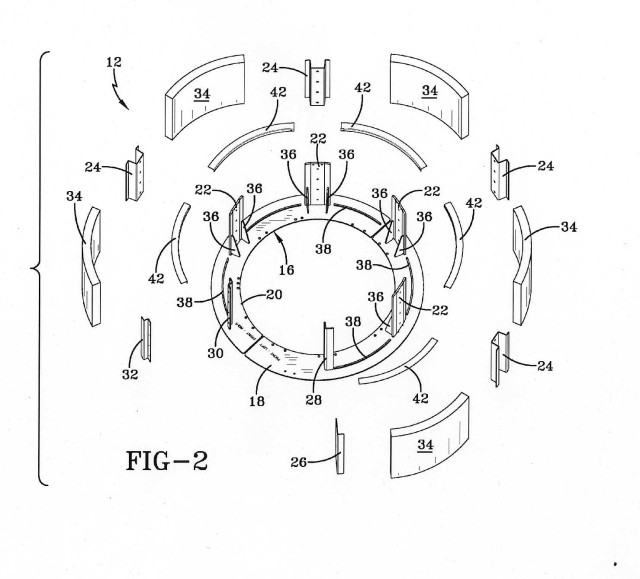

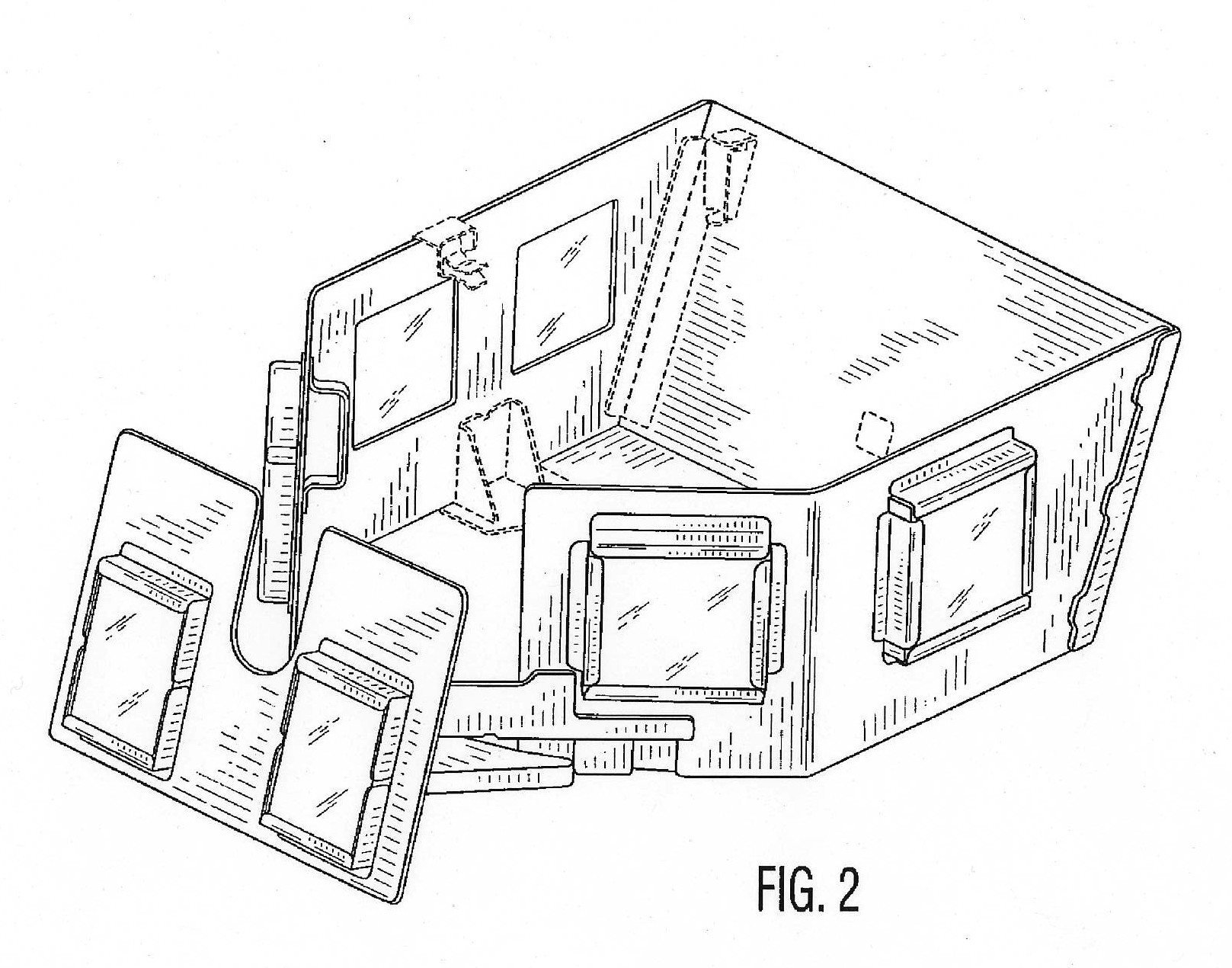

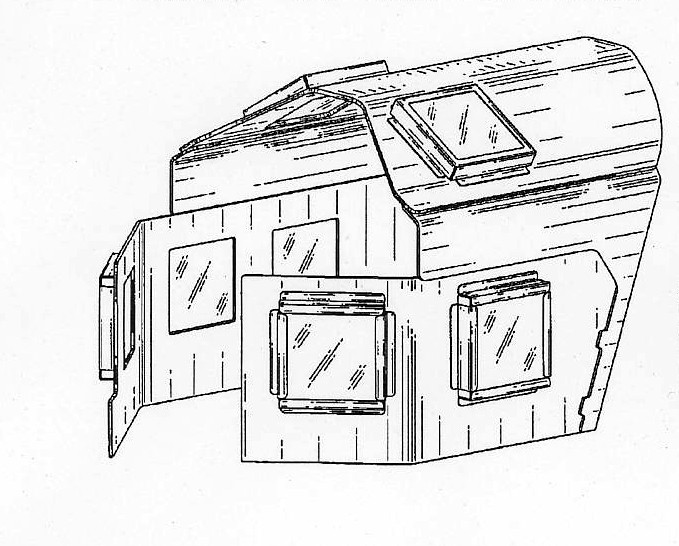

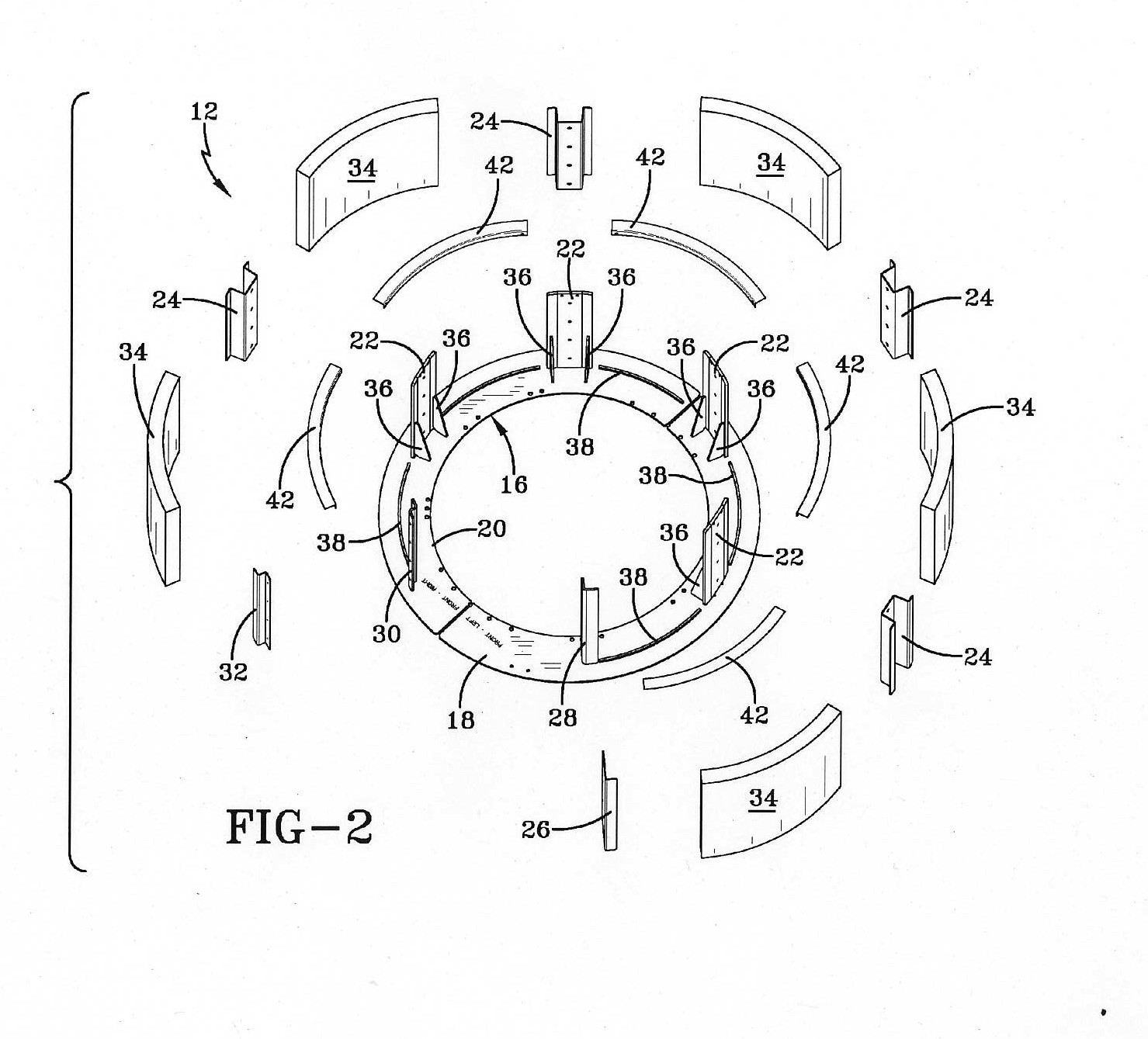

The prototypes went through strenuous testing to arrive at the optimum design, which featured unique combinations of solid and transparent armor to provide protection and 360-degree visibility. The design also gave gunners a high degree of mobility so they could fight more effectively.

Within six months, the OGPK went into initial production. Kiel said the Soldier-engineer collaboration was critical to meeting the Soldiers' needs so rapidly and to solving vexing, age-old challenges related to turret design.

One challenge was to configure bulky armor to provide protection while not restricting a gunner's movement and visibility.

That challenge has long been a subject in the gunner protection "stream of invention," the words ARDEC patent attorney Henry Goldfine uses to describe a conceptual flow of ideas in a technology's progress from "prior art" to state-of-the-art.

The stream concept is meaningful when determining whether technologies are truly "new, useful and non-obvious," shorthand for the threshold that an invention must cross to qualify for a patent.

The Army obtained a patent for the OGPK, and later, five related patents to meet emerging combat needs.

According to Kiel and Goldfine, obtaining patents was critical to meeting the Soldiers needs because it sidestepped potential disputes down the road that could have cost the Army valuable time and money.

But no one ever said getting a patent was easy.

The difficult task of obtaining a patent

"The inventor is usually convinced that his idea is new, has merit and is novel," said Kiel.

"The challenge is that you have to convince your peers, the patent attorney, the IEC (ARDEC's Invention Evaluation Committee) and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office."

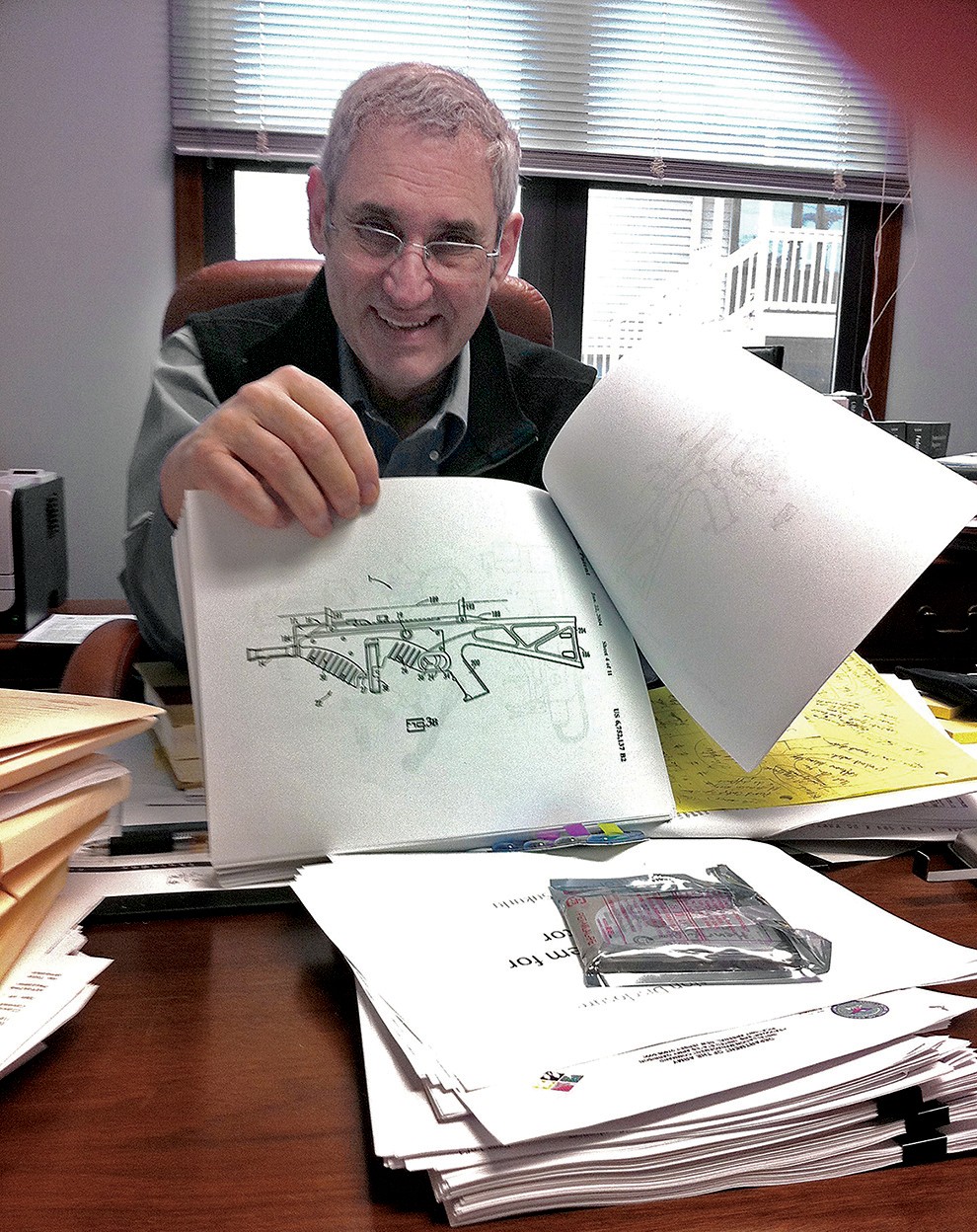

To start the patent process, Kiel said, the inventor researches, gathers data, consults other experts and a patent attorney, gathers statements and drawings over a "month or two" amid other duties and prepares to defend the invention before the IEC.

Considering that writing, filing and pursuing a patent application can be expensive and take years, the IEC is charged with deciding whether or not to file an application based on criteria outlined in Army Regulations 27-60, "Intellectual Property."

If the IEC approves a patent filing, an ARDEC patent attorney works closely with the inventor to write and file an application. "The application must tell a story to the patent examiner," Goldfine noted. That story highlights the inventive element so that the examiner will "get" whether or not it meets the patent criteria.

Being proactive, patent attorneys must anticipate what patent examiners might question. Even if the patent is granted, it may one day be closely scrutinized in potential litigation between the Army and an infringer.

Therefore, "all the claims must be technically supported or the patent could be voided in a court of law," said Goldfine.

Patent attorneys will write portions of the application -- the claims -- in arcane language to claim the "metes and bounds," or limits of what intellectual property the inventor believes to be his own, Goldfine explained.

Claims are judged compared to what has been presented before -- the "prior art."

"If the prior art is the same or close to the same, we won't file," said Goldfine, because the invention cannot be proven to meet the patent criteria.

"They say patent attorneys live in the prior art, and it's true," he said. Without understanding how things were, you can't understand how your invention is different."

By Goldfine's estimation, attaining patent attorney skills requires an apprenticeship of at least a few years, and to be good, at least five years of practice. Moreover, it requires degrees in law and a technical field, as well as passing bar exams through a state and the government patent office.

Yet substantial skills won't hasten the process of obtaining a patent. After filing, the application lands at the USPTO where … it sits.

With a current backlog of more than 700,000 applications, one of about 6,900 patent examiners will process a "first office action" more than two years after arrival on average, according to the government patent office.

"They very, very, very seldom grant a patent on a first office action," emphasized Goldfine. "Usually you get a rejection."

Sometimes rejections may force attorneys to reconsider the patent claim, but they often continue -- sometimes beyond rejections marked "final."

This process may include providing amendments, legal arguments or data, filing requests for continued examination, paying additional fees, appealing before the Patent Board of Appeals and Interference and, finally, to a federal court.

All through the basic patent and appeal process the inventor is intimately involved, providing technical insight and data.

"It's tough to focus on the patent process when you have an urgent requirement to address and warfighters are depending on your solutions," said Kiel. However, that didn't prevent his team from juggling competing demands and supporting the attorney throughout the patent process.

So why bother?

With its expense and seemingly glacial speed, why go through the arduous patent process?

"We want to avoid paying costs for something we invented," explained Goldfine. "Industry has the motive to develop exclusive rights and sell to us."

If the Army doesn't patent its inventions, a private company could develop, patent and claim the same invention, and that can result in higher costs.

"Time is also a factor," said Goldfine. Failure to patent an invention can affect the government's ability to license the invention so that manufacturers can fire up the production line.

The Army can proceed to equip Soldiers with new technologies without having to await a patent by obtaining a patent pending stamp which lists the date the patent was filed and acts as a "warning" to would-be infringers, according to Goldfine.

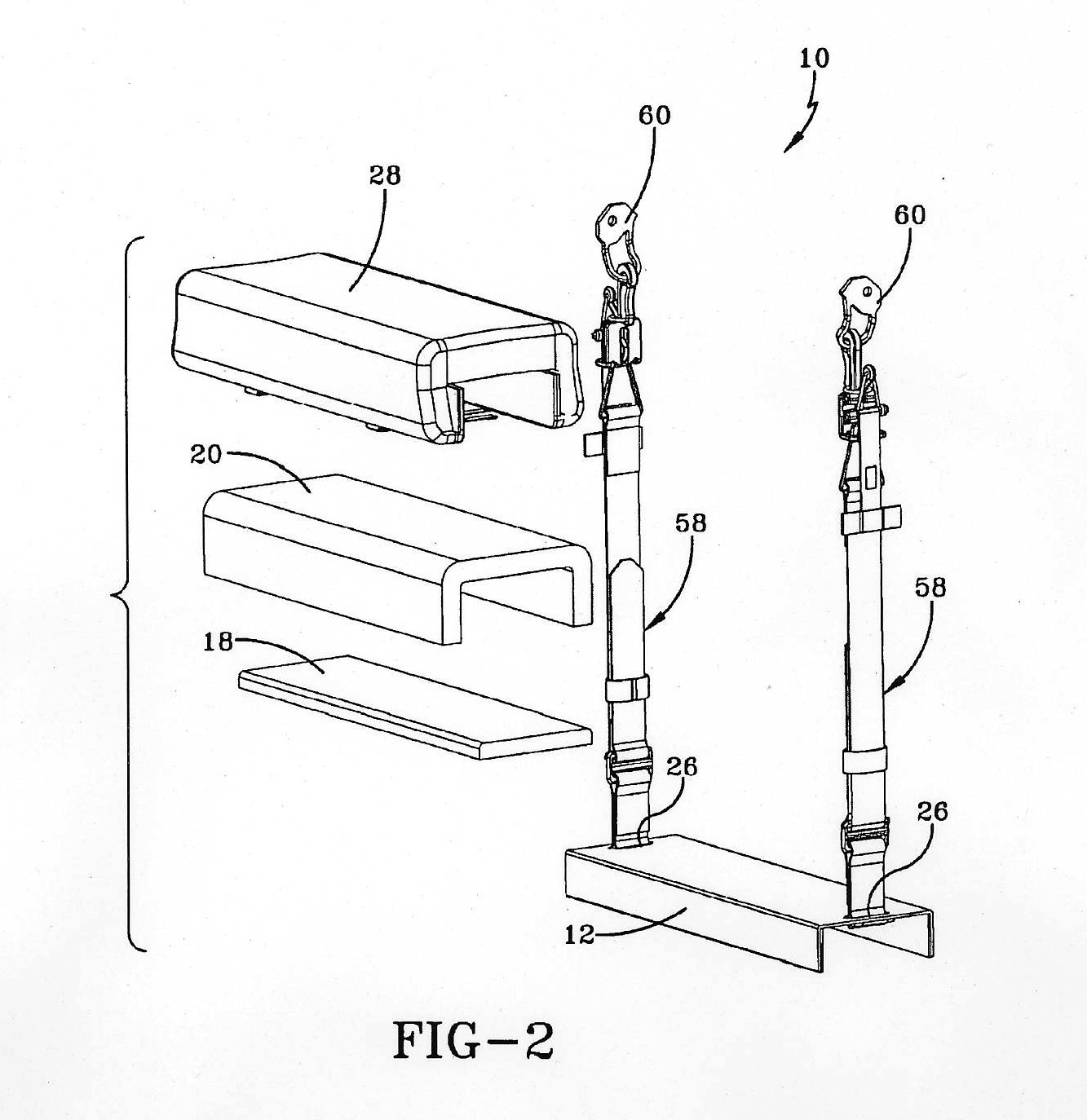

Patents fit along with other factors to ensure a speedy delivery of OGPK.

After designing components, Kiel's team had ready access to ARDEC's Prototype Integration Facility, where it built, refined, fitted and then tested prototypes to prove their designs were effective and safe.

Before going to production with any patentable design, Kiel said he always strives to file a provisional patent application to obtain the patent pending stamp before going to a manufacturer with the production data.

With final specifications in hand, the Army solicited proposals directly from qualified manufacturers. The government-owned data enables full and open competition for production, which drives costs down, Kiel said.

The OGPK has a design patent, which carries the right to exclude others from copying the OGPK "look," according to Goldfine.

This provides Soldiers a guarantee of sorts.

"With OGPK, Soldiers know what they're getting," said Kiel referring to the Soldiers' role in optimizing the design.

He explained that if a manufacturer copied the design but used different materials, a Soldier might think he has a protection or feature that wasn't there when needed in the heat of battle.

"It is very important for the government to maintain intellectual property rights for its designs," said Kiel. Obtaining the rights ensures that Soldiers receive "certified" armor kits with geometry and protection levels that meet the Army's detailed specifications.

As for the "gates" and "rigorous steps along the way" toward obtaining a patent, Kiel said, "They're for a good reason. You have to prove the idea is valid and adds to warfighter capability."

The OGPK, Weapon Elevation Kit and Overhead Protection Kits have each been selected as Army Greatest Inventions, an award program in which combat Soldiers choose the winners.

Making Innovation a Priority

The OGPK is an example of a broader philosophy that ARDEC is embracing. This approach includes using patents as:

• A truly objective measure of state-of-the-art inventiveness

• A method to recognize the personal efforts of inventors and to attract and retain top engineers and scientists

• A way to leverage in-house innovation to get better partnerships with industry

ARDEC employees obtained 30 of the 119 Army patents granted in 2009, and ARDEC patent applications have increased from 36 in Fiscal Year 2008 to 67 in FY 2010.

Nevertheless, "There's more we can do as an R&D;center," said Kiel. "Our future lies in innovation: out-of-the-box, groundbreaking inventions that provide significant warfighting capability."

Another factor is propelling the pursuit of patents.

"There is an increasing burden on the government to do intellectual property development," said Andrei Cernasov, one of the architects of the Innovative Developments Everyday for ARDEC (IDEA) program.

Originally a consultant for ARDEC's innovation initiative, Cernasov is now a permanent ARDEC employee. His research into industry trends indicates that many companies are shifting their research and development centers closer to more profitable emerging market areas like Asia.

Should there be a decline in domestic industry innovation, Cernasov aims to help ARDEC prepare. "The capability to do innovation is proven in government labs. It leads to cheaper, better-performing systems."

Furthermore, Cernasov said being a center known for innovation breeds more innovation. "If we can show the A-level graduates there's a place for them to be creative, we'll attract a better workforce."

Consequently, one of the challenges is growing engineers from within who are knowledgeable and capable of pushing the state-of-the-art. "The majority of intellectual property comes from design engineers," said Cernasov.

"Every engineer hired here is hired as a design engineer," said Cernasov.

"The tendency is to acquire transactional skills and lose design skills over time." Transactional engineers know the state-of-the art in their technological area, but their role is to generate or monitor contracts, said Cernasov.

ARDEC needs plenty of transactional engineers, he said, but he teaches any ARDEC employee about the innovation process to nurture innovation as a capability within the center.

The IDEA program is sheparded by three "champions" and it provides five innovation catalysts -- Kiel among them -- who mentor and encourage new inventors and link them with collaborators during the design process.

ARDEC's IDEA initiative also provides facilities equipped for innovation that house prototyping capability, libraries and online services to aid in patent research and documentation.

Private industry's size and motivation to innovate continues to make it a vital partner and resource to obtain Soldier capabilities, according to Cernasov.

However, the center wants to leverage more Cooperative Research and Development Agreements, or CRADA, and other innovative arrangements with industry to contain costs.

A CRADA is an agreement that allows industry and the Army to work together on a project. A company gets the Army's assistance to develop the technology for use in the commercial market. For its part, the Army gets technology developed that it needs for Army purposes.

A key to the CRADA is that it allows the Army to share the patent license, which can lower the cost of products that Soldiers use to gain the upper hand in battle.

"They're a win-win for the Army and industry," Cernasov said of CRADAs.

Related Links:

ARDEC receives permanent symbol of Army appreciation

Picatinny lands 3 of the Army's 10 greatest inventions of 2009

Picatinny invention gives Soldiers 80 degrees of firepower

Continuous Army innovation yields improved gunner protection

Social Sharing