Everyone has a routine, be it an individual or an organization. Routines promote organizations and familiarity, and can even foster expertise. The Army builds Soldiers' discipline with strict routine, and civilians find comfort in the daily routines of their lives. But when a routine is disrupted, how do you adapt? How do you respond when your morning commute is shattered with the news that your office has been collapsed by a plane?

If you're a Soldier, you report to work anyway--the epicenter of the crisis becomes your place of duty.

On Sept. 11, 2001, hijacked American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the western side of the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m., killing 184 people and eventually causing a partial collapse of the building. Mere minutes after the impact, the National Guard mobilized.

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Steven Mueck, an Active Guard Reserve pilot with the Joint Force Headquarters, District of Columbia National Guard, was on his way to work at Fort Belvoir, Va., when he heard about the attacks in New York City on the radio.

"By the time I got here, we had gotten word that that something hit the Pentagon and more airplanes were en route," Mueck said. Once he arrived at his office, he found a helicopter and flew to the Pentagon to help.

"I launched in a Huey, a UH-1, with a Chief Warrant Officer 2 Trent Munson and Sgt. Gary Elam, and we went up, landed at the Pentagon (and) started talking to those folks. As it turned out, they had doctors and corpsmen and nurses at Walter Reed that needed to get there," Mueck said. "We spent the rest of the day bringing doctors and morphine and things like that to the Pentagon and taking other things back to Walter Reed on the reverse trip."

The magnitude of the situation didn't hit Mueck until about an hour into his mission, when he realized he was the only person talking to air traffic control at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Arlington, Va.

"We were having a conversation instead of me trying to break in and wait for airliners, stuff like that," he said. "It was just me and him."

Mueck is the tactical operations officer for his unit, responsible for mission briefs and flight plans, schedules, assignments and coordination. Before 9/11, the JFHQ-DC medevac unit operated much the same way it does today, adapting to the situation as it happens. Mueck credits their quick and flexible response as the reason they were successful in assisting after the attack.

"We got the right crews out there, we went and did our job, we had people on standby. We had other aircraft up there for 72 hours after that on standby in case somebody was found," he explained. "We actually had a lot of things in place already that turned out to work very well for us."

Though Mueck and his crew adjusted quickly to the crisis, it was never a job he imagined he would be doing.

"It was beyond me that anything like that could ever happen here in the United States. To be doing what we did was a sobering experience, and quite frankly, something I hope I'd never do again."

Not everyone in the D.C. Guard immediately mobilized to the Pentagon, however. Staff Sgt. Marcus McCauley of the 273rd Military Police Company was sent to ground zero in New York, not with the Guard, but as a member of Washington's Metropolitan Police Department.

While in New York, McCauley performed honor guard duties for the fallen police officers and firemen who had responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center.

"Just being up there and seeing stuff, you know the whole site--it was just unbelievable to see how much destruction there was in the city," he said.

"And then also, to see all the fallen officers," McCauley paused, collecting himself. "That was a little rough."

When McCauley returned to D.C. after two weeks, he deployed with the 275th MP Company to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., on a law and order mission, providing base security because of heightened threat levels nationwide.

Of course, some of the most difficult duties during the crisis happened amid the rubble: search, rescue and recovery. National Guard chaplains from as far away as Pennsylvania were called in to counsel recovery workers in the weeks immediately after the attacks.

Colonel William Lee, Joint Force Headquarters chaplain for the Maryland National Guard, got the call shortly after he heard the plane had hit the Pentagon; he was asked to go to the Pentagon as team leader for those chaplains who could come from Maryland.

"When we got there, we fell in on the chaplains' section," Lee said. "There were chaplains from Virginia, D.C. Guard, Maryland Guard, West Virginia, Pennsylvania (and) Delaware Guard, because we were the surrounding states who could drive in."

Assigned to the Pentagon's North Parking lot in support of the FBI chaplains, Lee worked the 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift. The parking lot was marked in grids, he explained, and earthmovers brought over rubble to be sorted through. Some 200 recovery workers and intelligence agents went through the debris.

"They would go through it to try and find either pieces of the airplane, human remains or sensitive intelligence-type material or documents," Lee said.

Everyone wore white biohazard suits, complete with respirators. Generators throbbed, powering lights so the crews could work through the night.

"Our job was to provide spiritual counsel and support to the folks on site, and that would especially happen in the middle of the night. About…two to four, there would be a break and everybody would come off the pile," Lee said. The Salvation Army would come by during that time, supplying socks, dry T-shirts and hot coffee.

A nearby hotel served as a family assistance site, where there were boards with names of the victims. Families would wait there for word from Lee and his colleagues that their loved ones' remains had been identified.

Lee said that in addition to the anxiety and uncertainty surrounding the event, finding human remains was difficult. Remains would be packaged in clear plastic bags, then into larger orange bags and finally transferred to a full body bag. The chaplains would recite prayers for the dead from the different faith groups.

"We did that out of respect for the remains, but also so the families at the (hotel) could know, and were told, that everything possible to show respect for the remains of (their) deceased loved one had been done," Lee said.

Over the course of one evening in particular, the crew found a Barbie doll and a set of "pretty pajamas."

"You could almost feel a ripple through the group with that," Lee said. No one had thought about children being in the attack. Soon after the pajamas were recovered, the crew found a child's foot.

That morning, Lee went to the hotel and looked at the list of victims. On it was a family with an 8-year-old daughter, Zoe Falkenburg, who was a lover of dance with perfect ballerina feet. The family was on Flight 77.

"At that point, I began to cry because I realized what we had found. It was about week three, and it all brought it home personally," Lee said. At the time, his daughter was 11 years old.

Lee said his time at the Pentagon changed him both professionally and personally, helping him stay focused on what is essential in his life, like faith and family, which makes him a better chaplain.

"Up until then, the Guard was the usual one-weekend-a month, two-weeks-a-summer scenario," Lee said of the National Guard's operations before 9/11. "Now, that's how often we get people to go home, rather than when we're drilling."

"People talk about the fact that we didn't have any contingency plans, but I don't know how you can plan for the unthinkable," Mueck added.

The Guard has also done much to change its public perception since the attacks, Mueck said. "I think what may have changed (are) the attitudes. I think before that, there was a conception about the National Guard--a peacetime flying club and things like that--and I would say to a certain extent that was probably a fair assessment.

"Maybe we didn't take things as serious as we should (have)," he continued. "But now almost all of our folks have had a chance to deploy." The Guard as a whole realized the importance of their training and the fact that they can be called upon at any time to use it.

The Guard is training in the same way as the rest of the Army, regularly and to the same standards, McCauley explained, and is prepared to respond if there is ever another 9/11-like crisis.

"Now, we're a seamless part of the total team," Lee said, adding that the Guard has become more integrated into the Army's communication system and can plan for various contingencies in advance. The equipment, training and response to state emergencies have even improved in the years following Sept. 11.

"We continue to learn from our experiences and try and project into the future so we can remain adaptable," Lee said.

NEW GALLERY SHOWCASES GUARD'S LEGACY

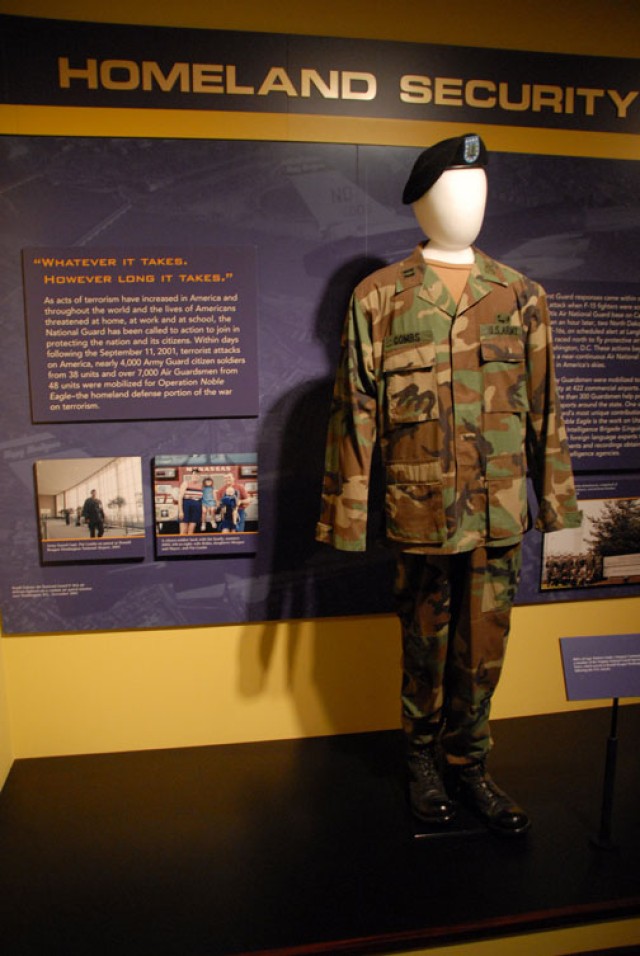

The National Guard Educational Foundation, established in 1975 as a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that advocates for the Guard through education, is enthusiastic about telling the Guard's story. Situated in the National Guard Memorial Building just off Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, the office also houses a museum and library dedicated to the Guard.

Cathleen Pearl, deputy director for the Educational Foundation, said that this year would be an exciting year for the Guard and the museum. On Dec. 13, the Guard will celebrate its 375th birthday and it will also recognize the 10-year anniversary of 9/11.

"We're going to open (a) new gallery which will cover from Sept. 11 to the present, that very transformative decade," Pearl said. That exhibit will be a permanent display in the larger gallery at the museum.

She explained that since 9/11, the Guard has increased its operational tempo, deploying almost every brigade at least once, and keeping retention rates high. Pearl was in the Missouri Air National Guard for six years before moving to the East Coast as a civilian and believes the Guard's increased presence at home is good.

"Their presence since 9/11, although being a little shocking, is comforting for people," she said.

Pearl hopes the new exhibit and overall gallery will help reintroduce people to the Guard.

"If people aren't familiar with Guardsmen, the first thing that will pop up is Kent State," she said, "and there's a lot of misconceptions about the Guard, but they're an operational and ready force, they're not a reserve, they're not sitting on the sidelines. You can't go to war without the National Guard anymore."

Pearl believes the gallery will be a source of pride for Soldiers, allowing the different components of the Army to see what the others are doing.

"It's eye opening to see in total what the National Guard does, it's hugely impressive, and to be a part of that, I think, is really a source of pride for people when they come in," Pearl said.

The Educational Foundation hopes to open the gallery in December 2011, memorializing the nearly 700 Guardsmen killed in support of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and honoring the 375-year legacy of the Guard itself.

"Guardsmen are some of the most giving (people)," Pearl said. "If you need help, they are there."

For more information about the National Guard Educational Foundation and to learn more about the 9/11 exhibit visit: www.ngef.org.

Social Sharing