"The challenge for all of us," Brig. Gen. Michael S. Tucker asserted, before beginning the Army Medical Action Plan Assessment Conference, in Landsdowne, Va., late last month, "is to ensure we stay focused on our wounded Soldiers' recovery."

Brig. Gen. Tucker leads the Army Medical Action Plan, a restructuring of the way Warriors in Transition receive treatment.

For eight months, now, the Army Medical Action Plan has sorted through the systems which provide health care and support services to the Army's Soldiers and Families in need. These ill and injured Soldiers, and their Families, often have felt helpless against those systems, so AMAP was set up to make the systems easier to use.

Many patients experiencing these challenges say they welcome the positive changes.

"There's probably not a thing on my mind that I can say bad about this place," said Spc. Marco Robledo, as he readied for his afternoon session in the Upper Body Room at Walter Reed Army Medical Center's new physical rehabilitation facility. "I just wish I were home," added the native Arkansan.

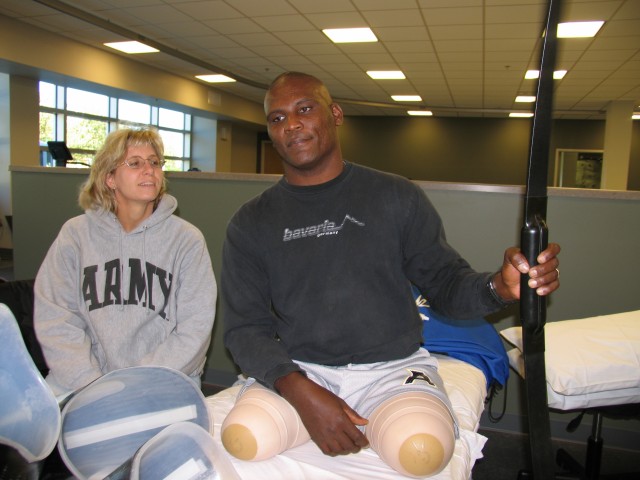

Under AMAP, recovering patients get individualized care, with attention to their specific needs, including choices about where to undergo recovery. Lt. Col. Greg Gadson was a battalion commander when he nearly died from his wounds: "My opinion," he said with a shrug, "it's a lot better here," comparing WRAMC's facility to those of his other choices.

Still, Lt. Col. Gadson said, AMAP and his care-providers -- as good as he believes they are -- "can't read your damn mind!" Throwing his torso forward for emphasis, "I understand how to advocate for myself, 'cause I'm a little senior, but I think some of these (WTs) are a little intimidated by the Army," and in some cases the system.

Kim Gadson, quietly showing pride in husband Greg's progress on his upper-body exercises, shared his sentiments, in a way, about family members new to the Army. "A lot of perceptions they bring with them," the soldier-turned-teacher hesitates, "are sometimes justified (by their experiences in the early stages of the process)." The Gadsons' knowledge of how the Army works comes from their nearly 40 years of combined experiences with advocating for themselves.

Warriors in Transition can ask for help from a close friend or family member, with the Army picking up much of the expense for them.

"My Dad had to go back home," Spc. Robledo told a facility employee, looking resigned. "Mom and my brother are here, and I like that," putting a smile back on his face.

Among those needs, some WTs and their families see real progress in their access, now, to services unavailable to them when they began their recovery, even if the transformation is unfinished.

"Now, I know they're trying to fix it," said Lt. Col. Gadson, "but life goes on," he added, taking personal responsibility for his share of his progress.

Asked about what people can complain about, Spc. Robledo points with the right arm he now has to make dominant, in the absence of what his nearly fatal injury in Iraq cost him. "I'm glad to learn how to use it," he said of his also-prosthetic new left leg. "I think they're ungrateful," speaking of some complaints he has heard about having the help they're getting, or just being alive.

One major reason for that progress is the "Triad of Care," said Col. Jimmie Keenan, an Army nurse, and chief of staff for the AMAP team. "Each patient we identify as a Warrior in Transition gets a physician, a nurse case manager, and a Noncommissioned Officer cadre member assigned to that patient."

Individualized care like this helps the Soldier keep up morale through recovery. The cadre make sure the Soldier follows the healing regimen lain out by the physician and case manager, and the medical experts have a more productive relationship with the Soldier and Family.

Before putting these processes in place, the Army medical community had a much more difficult fight to keep the warrior on the road to recovery. Describing how the process began, Col. Kevin Garroutte said they were: "making plans without involving customers." He is one of the senior AMAP staff officers helping to develop the Human Resource requirements for WTUs.

Garroutte explained the usual requirements for Human Resources didn't fit the needs of many WTs or their families. "That's one reason we're trying to meet a basic staffing requirement, while leaving open the possibility of adding more people, based on workload."

Some problems persist, though. "Are we doing the right thing'" asked Col. Keenan, "If not, why not, and what are we doing to fix it'"

"We have to be careful about going into our functional silos," Lt. Col. Rich Paz cautioned. Paz is a Plans and Operations Officer on the AMAP staff. He explained that could put the process back on square one: "We have to look at how each individual piece fits next to every other piece, or we could go in the wrong direction."

Social Sharing