FORT RUCKER, Ala. -- Thinking outside the box is not new to Army Aviation.

From the Civil War-era balloon corps to today's air/ground integration, Army Aviation has remained adaptive and a leader in military technology.

An early example of this adaptability was the creation of the American Glider Program in February 1941. Gliders were first used in WWII by the Germans, but it took only nine months after the first use of German Gliders in combat for the United States to form its glider program.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army increased the number of glider pilots to 1,000 and then in 1942 to 6,000.

Glider pilots were originally taken from the ranks of existing Army pilots, but the growing demand caused direct recruiting of enlisted Soldiers with no flight experience. These glider recruits were offered direct promotion to staff sergeant upon graduation.

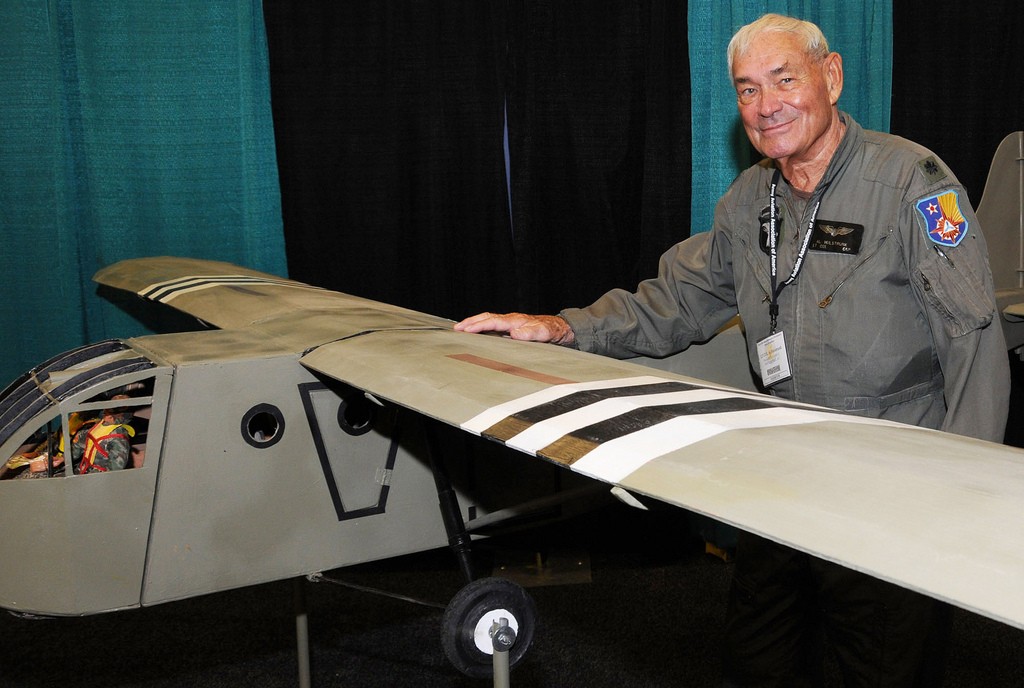

"We were towed in at 1,000 feet. You had to watch out for small-arms fire," said retired Lt. Col. Al Hulstrunk, a WWII glider pilot, who was at the Army Aviation Association of America's convention in Nashville in mid-April. "You would think you were in a popcorn machine - you would hear pop, pop, pop, and you would say, 'Oh, they are shooting at us.' It was the bullets coming through the tightly stretched fabric making the popping sounds."

Gliders were the stealth technology of their day. They could glide to their landing zone silently after detaching from their tow airplane, usually a C-47. Unlike paratroopers who would descend over a wide drop zone, the up to 15-seat gliders could deliver groups of troops and equipment in a small area. The gliders were made of mainly wood and fabric to save weight, but they could carry more than 4,000 pounds.

Hulstrunk said after landing his glider, "it was always pandemonium."

"We would land, open the nose, and get everything and everybody out. Since we only had a one-way ticket, we had to walk out."

He added that during the Rhineland invasion, he landed his glider 12 miles behind German lines.

"We had to walk out through the Siegfried Line, out the back door, and down across the Rhine River. We went in with what we could carry - that's about three days worth of food and supplies. So if the ground guys didn't get in, you were stuck."

The Army had a plan in place to retrieve the gliders by setting up the tow rope on poles and hooking it with a passing plane, but this was mainly used by the U.S. 1st Air Commando Force in the China-Burma-India Theater. After being "snatched" by a C-47, the glider would go from a standing stop to 100 mph and airborne within seconds. It was hazardous and required skill by both aircraft crews.

The stress on the glider was extreme and by the time the glider failed it would be most likely too low for the crew to bail out (they often flew without parachutes to allow more weight for troops and cargo), and too high for them to survive the fall.

Special operations forces worked closely with the glider crews.

"Then came Market Garden, where we really got bogged down. We needed to get munitions in so we dropped behind enemy lines, raised all kind of heck - a lot of our guys were special ops people. They went around cutting telephone lines and blowing up roads," explained Hulstrunk.

"At that time, the Germans couldn't do much about it. They would do whatever they were told, and nobody told the Germans they could turn around," he said, smiling, "They just weren't flexible."

Retired Gen. William C. Westmoreland had his thoughts on glider pilots.

"The intrepid pilots who flew the gliders were as unique as their motorless flying machines," he said. "Never before in history had any nation produced Aviators whose duty it was to deliberately crash land, and then go on to fight as combat infantrymen. They were no ordinary fighters. Their battlefields were behind enemy lines. Every landing was a genuine do-or-die situation for the glider pilots. It was their awesome responsibility to repeatedly risk their lives by landing heavily laden aircraft containing combat Soldiers and equipment in unfamiliar fields deep within enemy-held territory, often in total darkness. They were the only Aviators during World War II who had no motors, no parachutes and no second chances."

The final glider mission of WWII was during the retaking of Luzon in 1945, part of Gen. Douglas MacArthur's return to the Philippines, ending more than two years of Japanese occupation. By the end of the war, the U.S. had built more than 14,000 gliders and had trained more than 6,000 pilots.

Social Sharing