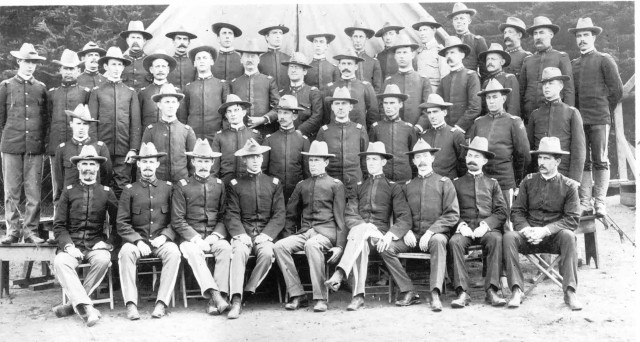

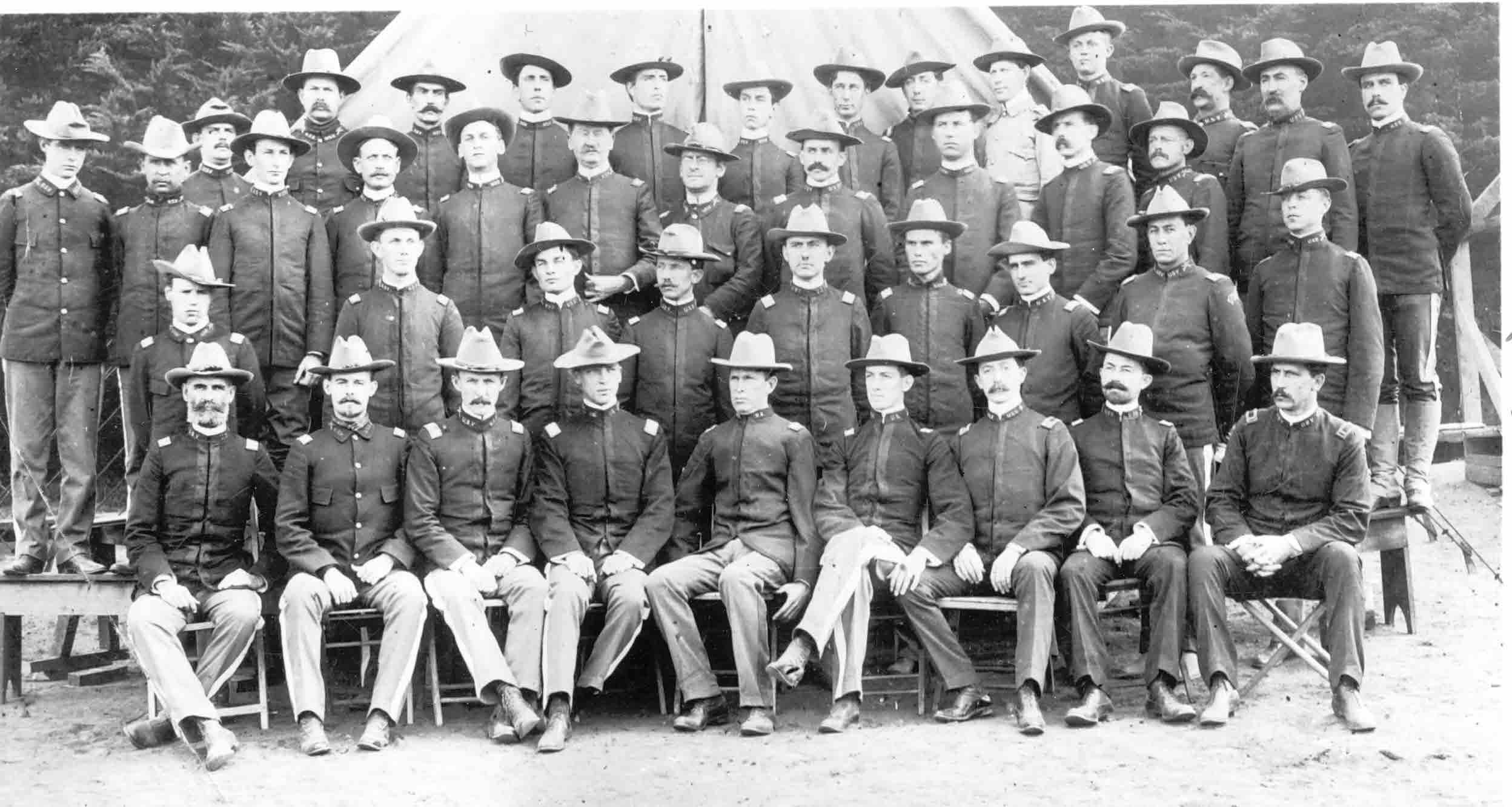

On the morning of November 11, 1899, the men of the 33rd Regiment U.S. Volunteer Infantry moved south toward San Jacinto. In their path was a series of irrigation ditches, water features, and rice paddies dissected by a road through the middle. As the men began crossing the muddy quagmire, gunfire erupted from the trenches and trees in front of them.

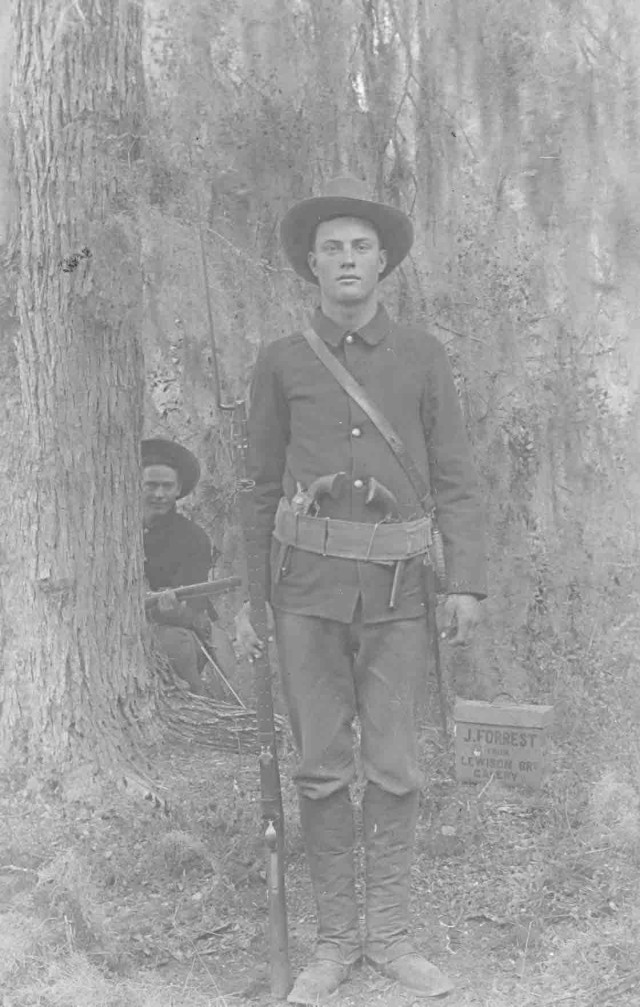

The Volunteers found themselves facing a force of 1,200 Filipino Soldiers under the command of General Manuel Tinio. Over the next two hours, a fierce battle was fought between the Filipinos in their entrenched positions and the Soldiers of the 33rd, many of them Texans. One of the American Soldiers, Milton G. Nixon of Company G (not a Texan but an Ohioan), described the battle in a letter home:

"About three miles from town fire was again opened upon our lines. At first it was right in front and not very heavy. Soon it grew heavier and heavier, and spred right and left. Over our heads, in the grass by our sides, in the mud, thru the trees, came the zip-whizz-sing-thud-splash of thousands of Mauser and Remington bullets. Our fire ran into heavy crashing volleys, and above all sounded the rapid "tat-tat-tat-tat" of the Gatling guns. The horses pulling one of the guns were killed, and half of our Co. were ordered to hand our guns to the other half and jump into the waist deep with mud road, and pull the gun, but soon got away. On we went on the double quick. We passed hospital, and saw the ground covered with dead and wounded from the advance guard. Major Logan was dying, the first Sergt. of H Co. was killed, our first Sergt. was shot thru the leg, and our Sergt. Major was shot thru the arm and breast. Dead Filipinos were everywhere. From all sides a heavy fire converged upon us. Suddenly we discovered that some of the Filipinos were in the tree tops (coconuts) and firing down upon us. We soon picked them out. We captured two lines of trenches, one at the point of a bayonet. Then we came to a river (Abra) We came thru a bunch of low bushes out on a gravelly beach of a river, not quite as wide as the Muskingum. On the opposite bank the ground sloped up to the Filipino's third line of trenches along a fringe of coconut trees. Just before we reached the water the man on my left was killed. I heard the "thud" of the bullet hitting him, and turned my head to see him drop his rifle and fall face downward with his face in the edge of the water. I went to dress his wound but when I lifted his head up I saw he was dead. We crossed the river, captured the last line of trenches, and forced our way into San Jacinto."

When the battle of San Jacinto ended, 7 Americans and 134 Filipinos were killed, many of those casualties to the single Gatling gun the American Soldiers carried and put into action. Among the casualties was Major John A. Logan Jr., son of Union General, Congressman, and Senator John A. Logan. Major Logan would be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for distinguished gallantry in leading his battalion during the assault.

The American Army routed the Filipinos and destroyed them as an effective fighting force. The war then quickly changed from a conventional one to that of guerrilla warfare, but the American Army was able to ultimately prevail. The Philippine-American War would not officially end until July 4, 1902, although the Moro Rebellion continued on until June 1913, effectively ending the Philippine-American War.

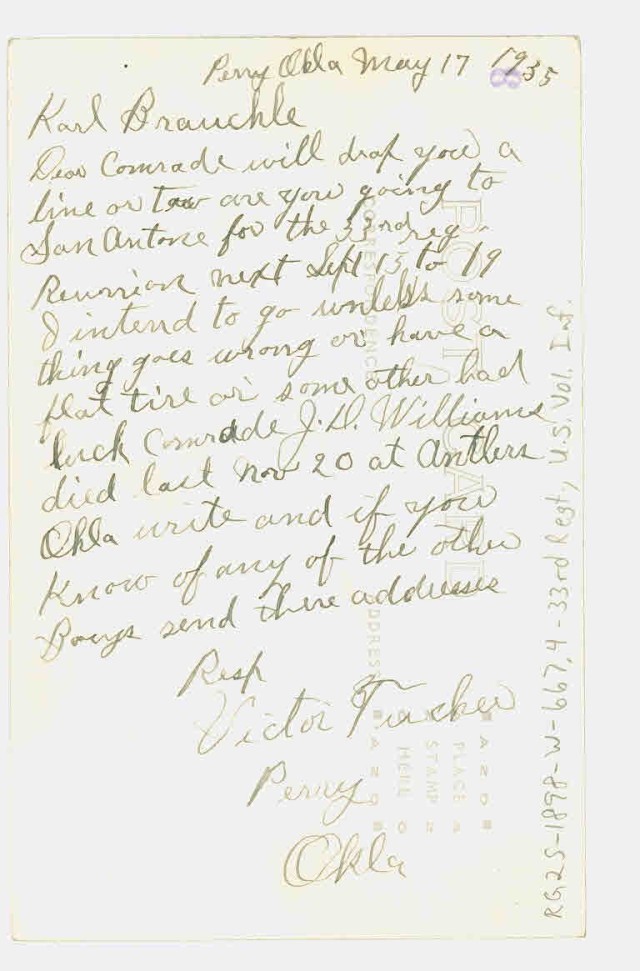

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center, 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021. Website: www.carlisle.army.mil/ahec

Social Sharing