The evolution of the Japanese press since August 1945 is unique in the annals of military occupation. Instead of the press being closed down, with only certain journals permitted to publish under license, General MacArthur directed that all Japanese newspapers and magazine continue to publish. The way to learn democratic free press procedures was by doing.

This confidence has been justified. From a regimented press--ordered by the Japan Board of Information what to print, how much to print and when to print--the Japanese newspaper and magazine press today has evolved into a thousand-tongue press, carrying to its readers diverse opinions and news. From an irresponsible press that projected false, misleading and biased news, the Japanese newspapers, in the main, have evolved into a responsible press that publishes a truthful, comprehensive and intelligent account of events.

The evolution was not achieved quickly. At the beginning the Press and Publications Branch of Civil Information and Education Section, SCAP, exercised rigid censorship; but that censorship soon became post-publication review. More and more, as the Japanese learned new principles, editors were placed on their won and met their increased responsibilities conscientiously. The point is that from the beginning of the Occupation editors exercised some responsibility; they were not silenced in the fear that they would disrupt the Occupation. It took courage to run this risk; but it paid off.

The MacArthur Press Code, basic directive upon which Japanese journalism has been reconstructed, was issued 19 September 1945. It stated well known Western journalistic principles, the most important point being: "News must adhere strictly to the truth."

Reorganization of the Japanese press followed immediately. This reorganization, designed to rid the press of those who were ultra-nationalists and militarists, was left largely to the Japanese themselves. Some interesting developments resulted. One was the unsuccessful attempt by the newspaper labor union to take over editorial control of the papers. Just as the new way of life in Russia was implemented by a dictatorship of the proletariat led by a doctrinaire intellectual elite, so here in Japan some of the newspaper labor union leaders proposed to establish a labor union dictatorship, programmed by an intellectual elite of Communist editors.

The Japanese publishers, editors and reporters were confused and bewildered by the climax in their nation's long history. False gods and false leaders had led the country to war. It was the extreme Right, with its anti-Communist slogans, its intense nationalism, its Emperor deification and its penchant for plots and violence, that was responsible for Japan's ruin.

Against this background, the Civil Information and Education Section, SCAP, projected the following definition of a free newspaper: "A free newspaper is a private commercial undertaking with a public function. It must recognize its responsibility to supply the public with a true report of the important events. This news must be presented truthfully, fairly and impartially. In its editorial columns, a free newspaper has the right to project the opinions of the owners of the newspaper or of the management selected by the owners. Freedom of press means the right to publish, without previous license, subject to the law of libel."

Such a concept was approved by neither the Japan Communist Party nor the newspaper labor union. Nor did the left-wing Allied Powers correspondents like it. The reactionary elements of Japan, on the other hand, held to the theory that a newspaper is a public utility and can be controlled by the state. But CIE stuck to its guns. It continues to stress in its seminars and its newspaper institutes that a free press must be a responsible, objective press; that the news must be reported truthfully, accurately, objectively and fairly; that news must be separated from editorial and reportorial opinion; that a free newspaper must be free to project the ideas of its readers in "Letters to the Editor" columns; that a newspaper should be a forum for the exchange of ideas on public men and public measures; and that the owners and management are responsible for contents.

The first major test of a free-press came early in 1946, sparked by the editor of the Yomiuri Shimbun, who pointed out the techniques of the Japan Communist Party for degrading newspapers, magazines, labor unions, universities, colleges, schools, farmers' associations, youth associations and religious faiths. This started a cold war of ideologies in the Japanese press. The Communists adopted Lenin's technique of confusing the terminology by calling Communist clubs, societies, federations and pseudo-political nuclei "democratic organizations." Communists tried to take over newspapers and news agencies; but the courageous stand taken by publishers, editors and reporters thwarted all these attempts.

The steady conversion of Japanese editors to the democratic ideal is reflected in the statement of a provincial newspaper editor: "Democracy along Western lines is a most radical and uncompromising revolution for us Japanese. Your Democracy is based on the idea that the people can govern themselves better than a dictator or a few around him can do it for them. Until General MacArthur liberated us we never believed in that theory; we never understood it. Our whole political background has been one of authoritarianism. It is easy for us to understand Communist dictatorship," he wrote, "but your type of Democracy is the most radical thing we have ever experienced in our country. It requires us to think. I believe the mission of my newspaper is to witness to the truth and to advocate justice and law and order. I think all of our newspapers should do just that, and moreover we should argue editorially for pure, austere and undiluted democratic processes. I think we should not only reject Communism with its lies, deceits, lawlessness and murder, but I think we should also reject the idea that Democracy is subservient to an economic system that measures life solely by material values."

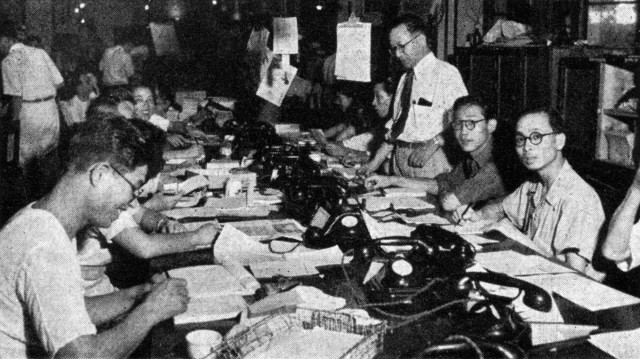

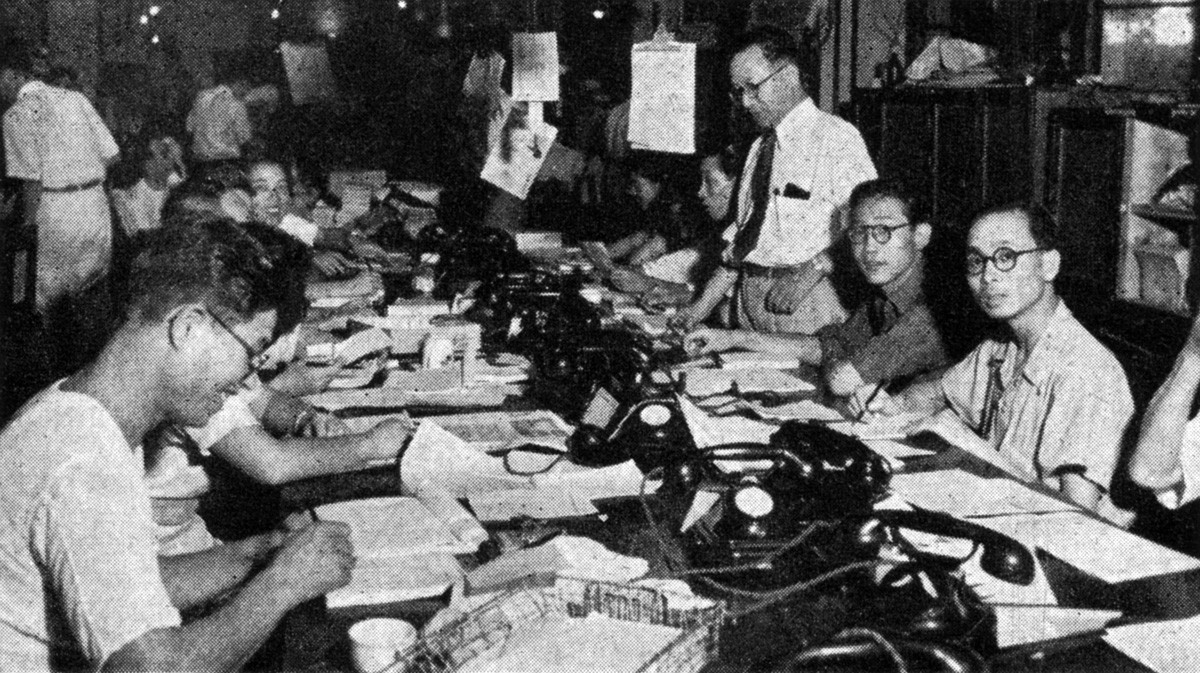

The Japanese newspapers of their own accord organized the Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association, with its ambitious goal of seeking to create the most responsible press on earth. Today there are more then 130 daily newspapers in the Association, with a combined circulation of 19,500,000.

While at first the Japanese editors had difficulty in differentiating between freedom to comment and libel, there are few today that carry libelous articles, and while there was difficulty in keeping editor-reporter opinion out of straight news reporting, today the majority of the responsible press keeps news writing separate from opinionated writing.

Great though its strides have been, however, there are in Japan no newspapers comparable to The New York Times, Dallas News, Sacramento Bee, Burlingame Advance, The Christian Science Monitor, Palo Alto Times, The London Times or your own home-town newspaper. The reasons for this may be attributed to old mores, lack of education on the part of the publishers, editors and reporters, and inability to absorb Western ideals quickly.

Japanese publishers, editors and reporters of responsible newspapers are making an earnest and valiant attempt to shed old more and to turn their backs on the pre-war philosophies. General MacArthur has inspired this strange and mysterious people to embrace a new life. in the vanguard of those who are striving to achieve the apogee of a truly democratic state are the newspapers and magazines that believe in and exhort for rationality, political order and responsibility, humanitarian brotherhood, personal initiative and free enterprise. These outnumber the Communist newspapers ten to one.

Living through a hot war and a cold war, Japanese publishers and editors know the important role played by ideologies and political maxims. In the old days they were the mere promulgators of the ideas and political maxims of the state and the ruling cliques. Today, they think for themselves and call no man an ideological boss.

Social Sharing