Not only the appearance but the content of the letters sent by the Japanese people to General of the Army Douglas MacArthur have changed significantly since the start of the Allied occupation. The most obvious inference to be drawn from the current mail's new look is that Japan's enterprising citizens have successfully completed their first three years' apprenticeship in democratic ways.

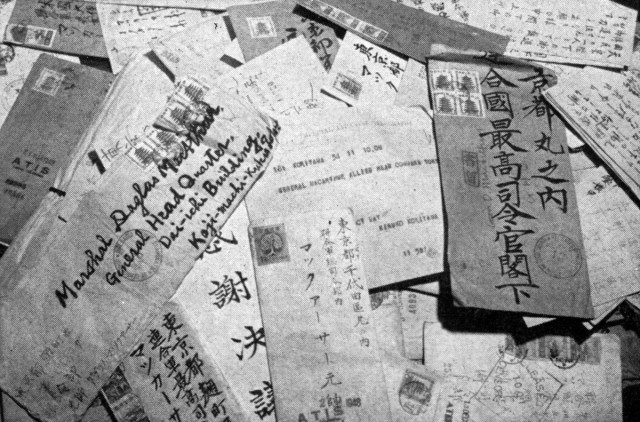

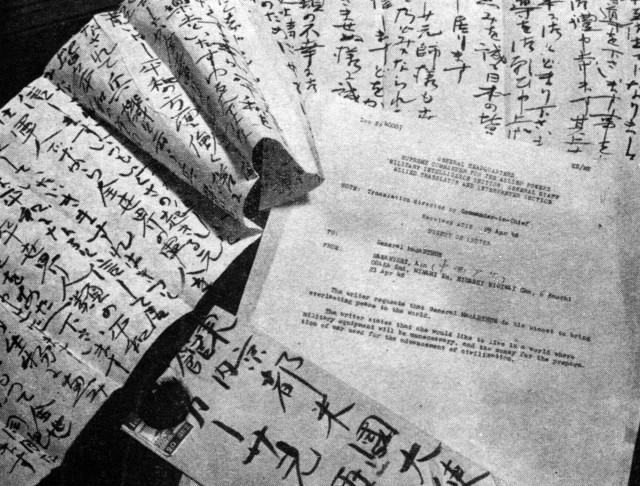

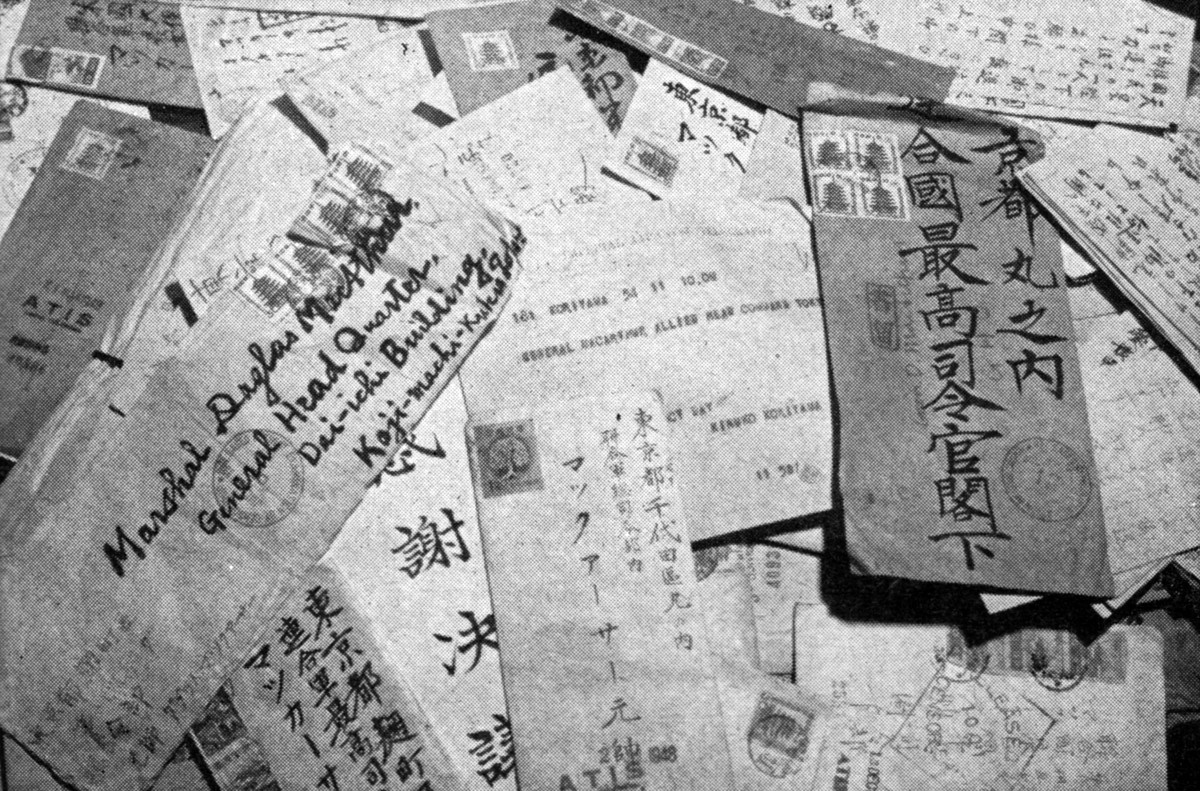

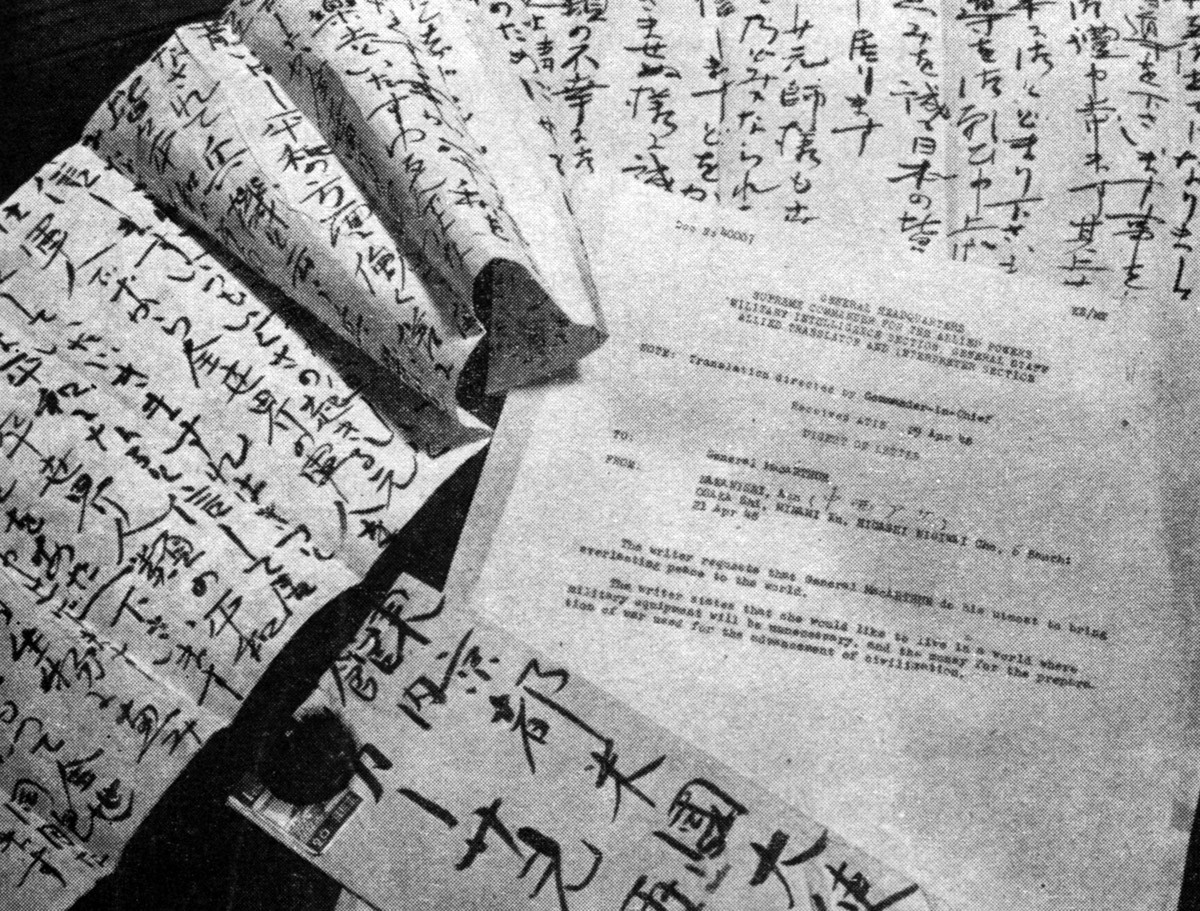

At present, most of the 1000 messages sent daily to the General are in familiar western-style envelopes. But back in the early days of the occupation, in the fall of 1945, the General's fan mail wasn't opened--it was unrolled. Then, in accordance with ancient custom, the Japanese were hand-painting their messages on traditional scrolls and, for added protection, were enclosing them in heavy wooden boxes. Scrolls ranging from 20 to 30 feet long by 6 inches to one-half yard wide might easily have been mistaken for artistic wall paper. Japanese postmen groaned kamate ne--"Oh, my aching back"; and United States Soldiers needed hammer, screw driver, and plenty of elbow grease to pry open the boxes.

While some of the first 100 messages to arrive were in solidly encased scrolls, others were inclosed in bulky rice paper envelopes of odd sizes, shapes, and colors. Mail was addressed to "General Makasa," "Mr. MadDaglas," "macther Marshel," and "Honorable Supreme Excellency His Highness Scap," among other illustrious titles.

The original one hundred letter writers, of whom six were women, were obviously taking no chances with this new "freedom of expression." Without exception, they wrote glowing tributes to the occupation policies, particularly such measures as the suppression of Japan's military clique, the emancipation of women, the issuance of staple food rations, and the reconversion of war industries. Many cautiously added requests for personal favors.

Six months later, in April 1946, the General received 2497 letters during a two-week period, including thirteen from women. Repatriation had become a primary concern. There were 1770 messages and one telegram signed by 5000 Japanese on this subject alone. The next most popular topic was clemency for war criminals, with 363 articulate supporters. The remaining letters were concerned with personal favors.

Many of the letters rambled discursively for 40 pages or more, with conclusions that bore little relation to the original subject. One thirty-page letter, for example, started out with a request for "Installation of Ice-Manufacturing Machine at the Japan Central Red Cross Hospital." The author then deviated into a heated discussion of "Japanese Women as War Criminals," and wound up with "A Private Proposal as to the Never-Been Tried-Before-And-Most-Sure-Method for Instantly Obtaining Complete Food Data of Entire Japan."

Two years later, in April 1948, the mail for General MacArthur approached 1000 letters a day. Most of them continued to be personal, asking assistance and airing grievances; but there were definite changes in outlook. Many writers objectively discussed political, social, and economic matters--democracy, the atomic bomb, Japanese repatriation, foreign trade, food, the housing shortage, education (especially coeducation), Korean independence, war, the status of women, religion, the United Nations, communism, and Japan's future. Opinions pro and con were freely given, in marked contrast to the earlier practice of writing only to praise. Also evident was a diminution in the fear of reprisals among the disapproving critics. They not only identified themselves by name but even gave their addresses.

Many writers took pride in their understanding of democracy and explained in minute detail how they arrived at their present knowledge. One correspondent disclosed that he grasped the full meaning of democracy at a track meet while watching a three-legged race. This "fullest cooperation" had impressed him as being the key to peaceful relations within Japan and among nations. Another convert realized the virtues of democracy after his house had been robbed, the thief caught by the police, and the stolen items returned. "I am sure," he wrote, "that it was the new democracy which was responsible for the polite treatment accorded me by the police, who even loaned me a fountain pen to sign my name and offered my wife and myself chairs."

A former Japanese Soldier, recently repatriated from a prison camp in Australia, wished to give his "heartfelt thanks to the Australians who treated us humanely and to the Allied people who liberated us to democratize." He wrote: "We who lost the right judgement suffered from the thoughts of the feudal militarism and poor circumstances. Nevertheless, the people in your union who was grown up in the good natured surroundings had treated us gentlemenlike regarding our individual rights, though wondering of our ferocity. We are quite ashamed and feel we can never give them enough thanks and apologies as we think of it."

Few correspondents criticize the principles of democracy, but one "common citizen" felt that Japan still had must to learn since "The Japanese, who like unusual things, grasped at democracy without understanding its true meaning." Another critic claimed, "You are remolding us after your pattern of democracy and it would take three generations."

Each day's mail to General MacArthur reveals that the Japanese people are quick to respond, with letters of appreciation, to any acts of kindness. Relief work by United States occupation forces after the earthquake disaster at Fukui evoked letters from all over Japan. Similarly, the periodic issuance of the staple food ration brings forth a flurry of communications from entire towns, as well as from individuals. The citizens of a community expressed "a thousand thanks deeply for your kindful assistance." A housewife wrote that she "never passed before staple food rationing house without feeling that entire world is family." Many who avowed "heartfelt gratitude" maintained that the food donations saved them from starvation.

An increasing number of correspondents evince a marked interest in religion. Many urge the spread of the Christian gospel as the most important element in the spiritual regeneration of the Japanese. One writer stated, "It is because the Christian teaching had not been spread enough in Japan that we are tasting the defeat of the present day, and I am sure the war would not have broken out had there been more Christians." Several attributed the commission of war crimes by the Japanese to the lack of Christian beliefs. These beliefs, one writer declared, are "the only foundation on which we can hope to rebuild a truly peaceful nation."

The many letters from members of the working class reveal a growing awareness of democratic rights. From individuals and labor unions come persistent requests for higher wages and better working conditions. Typical statements on this subject are: "I can't live on what I make" . . . "provide better working conditions for workers" . . . "Unions should teach the common man to be industrious."

The vague, lengthy, and highly imaginative letters of an earlier day are being supplanted, increasingly, by logical, succinct messages which stick to the point. This trend toward rational thinking is particularly obvious among the requests for accelerated repatriation of Japanese nationals interned in foreign areas. In marked contrast to previous hysterical appeals, sometimes written in blood "in the name of humanity," writers now base theirs requests on the terms of the Potsdam declaration, and substantiable statements of facts.

Holding their own in the mail are the Japanese women, who, individually and collectively, continue to advise the General of their appreciation for "his profound interest in and un-tiring guidance of Japanese women." Women's clubs frequently join forces in sending petitions carrying thousands of signatures in support of some civic project.

Letters from Japanese women clearly indicate the radical change from the traditional attitude of timid self-effacement to a growing awareness of public affairs. Such letters are written by housewives, school teachers, and pupils; by widowed shop-keepers trying to scrape together a living; by the mothers and fiancees of obscure war criminals, or of Soldiers awaiting repatriation. Almost invariable these letters begin with a work of appreciation for the "emancipation" and range into comments on politics, business affairs, and denunciation of Japanese public officials. Often, women writers relate their domestic crises, confide their love affairs, and even invite the General to weddings and family festivals.

Considering the lack of contact with the outside world which heretofore has prevailed in Japan, a surprisingly broad knowledge of international affairs is revealed in the current mail. Among the myriad suggestions received for reconstructing Japan and securing world peace were proposals for re-education of Japanese school teachers, a permanent United Nations League to police the world, and discontinuance of atomic bomb research. One writer asked that "birth control be taught to the Japanese people so that families might be limited to two children as in America."

The coming of Spring always beings forth a crop of well wishing poets and writers who send their stanzas and stories. One creative effort was the 350-line poem on 14 feet of rice paper scroll, beautifully illustrated with a fingerprinting of Mt. Fuji. In a follow-up letter, the author advised the General that he had decided to change two words in the 341st line.

The Japanese people continue to beg the General to remain in Japan. A farmer pleaded, "Marshal Macarsur stay in Japan forever but let me go to America instead." A miner attested to "a touch of loneliness" during the three days the General attended the Philippine Independence Day ceremonies and insisted that the "Supreme Commander must not leave Tokyo."

The bulk of today's correspondence reflects the increasing optimism with which the Japanese face the future. This attitude was summed up by one youth who declared, "I am glad the people are delivered of the Siamese twins of indolence and selfishness and now may enjoy the glorious and hopeful light of freedom and equality."

Perhaps one reason why so many common people write to the General is that they find him more approachable than their own emperor. As one housewife wrote: "The Emperor is too high and unapproachable for us. My letter to him will never be ready by him. His vassals will break it and throw it away under the reason of being too awfully, I know. Before closing my letter, I am very glad to support you and your work in Japan heartily."

The Japanese people's faith in the promised opportunities under a system of civil liberties grows stronger day by day. For it is the common people--the humble men and women who till the soil, do the housework, teach the children and work in factories and offices--who now write to the General on a man-to-man basis. It is they who have written: "We would like to make our country the symbol of peace and culture. We believe it possible," and "We desire you to lead us so that our hope and endeavor to the brilliant future should be realized."

Social Sharing