The signing of the Instruments of Surrender, on 2 September 1945, brought an official end to the smoke and roar of battle in the Pacific. With the ushering in of peace, policy directives from the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington gave the Supreme Commander powers and discretion to use the Japanese government and its agencies, including the Emperor, to accomplish the Occupation mission. The Supreme Commander thereupon established a supervisory military administration over Japan, inaugurating a new and unparalleled chapter in the history of military government.

An organization was set up immediately. On the policy level, General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, was created. This dignified title, however, is used rarely by the Occupation forces and by the Japanese. SCAP is sufficient; or sometimes GHQ. Up country Japanese officials and civilians, alike, know SCAP and Mac Kasa Shireibu.

On the operational level, military government units of both the Sixth and the Eighth United States Armies were used. With the inactivation of the Sixth Army, the entire responsibility was placed upon the Commanding General, Eighth Army. Here again, the terminology commonly is shortened to Eighth Army, or just MG. When referring to the Eighth Army, the Japanese usually say Hachi Bun. To them, military government is Gun Seibu.

SCAP itself is a large general headquarters, in which are centered the responsibilities for directing the Occupation of a country of 80,000,000 people. The high policy-making body for the Occupation of Japan is the Far Eastern Commission, in Washington, comprising representatives of 11 nations which contributed to the default of Japan. Policies adopted by the far Eastern Commission are transmitted to the Supreme Commander as directives by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The staff sections of SCAP translate general policy into specific directives to the Japanese government. To all in the Occupation these orders are known as SCAPINS. Only GHQ issues orders and directives on occupational matters to the Japanese government. No other echelon of command has that authority.

Upon receiving a SCAPIN, the Japanese Cabinet assigns the measure to the appropriate ministry, board, office or committee. Within a given time, the agency must produce a workable plan, then start the machinery for it accomplishment. To complete some tasks, all four levels of the Japanese governmental structure may be called into play--the national, prefectural, city, town or village.

During the past two years, the ordering phase of the Occupation has given way to the guidance phase. The number of SCAPINS has diminished gradually, and more counseling and advisory conferences and discussions have been held with Japanese officials.

GHQ holds the central government responsible for the proper fulfillment of the SCAPIN. The Japanese officials, in turn, must arrange to carry out their instructions by all available means, at the various governmental levels. The Cabinet, as the executive branch, is normally, "the government." If cabinets fall and new ones are formed, SCAP policy continues nevertheless; for SCAP uses the Japanese government; it does not support it.

How does SCAP know that the directives given to the Japanese are being carried out' This is the work of military government, or Gun Seibu. The responsibility for implementing occupation policies rests principally with the COmmanding General, Eighth Army. To execute the military government function, as contrasted with tactical or purely Army matters, the Commanding General has in his headquarters the Military Government Section. GHQ makes it policies known to the COmmanding General, Eighth Army, through command letters, circulars and communications. Sometimes it suggests action informally.

The Eighth Army Military Government Section is organized in five divisions, which, in turn, are subdivided into branches: (1) The Administration and Personnel Division includes branches for officer-civilian classification and civilian personnel administration. (2) The Economics Decision branches are concerned with Manufacturing and Industry; Labor, Trade and Commerce; Imports and Exports; Accounting; Price Control and Rationing; Utilities and Natural Resources. Other divisions are (3) Finance and Civil Property; (4) Legal and Government, comprising Courts and Law; Political Parties; Prefecture and Municipalities; and (5) Social Affairs, including Civil Education; Public Health; Public Welfare; Repatriation; and Civil Information branches. In addition, the Military Government Section supervises the United States vaults of the Bank of Japan, Tokyo, and the United States vaults in the Osaka Mint; and it conducts a school for military government personnel.

The Section--composed of 47 officers, including a chaplain, 38 noncommissioned officers and enlisted men, and 72 civilians--is directed by a brigadier general and his executive staff. Many of the civilians are of professional caliber and exercise the authority of equivalent officer grades.

The work of the Section is tri-functional. Command instructions come down from SCAP; proposals and suggestions come up from the two corps headquarters or the teams, or they may originate in the Section. Frequently, as a result of work done within the Section, the Army commander makes recommendations of his own to SCAP, suggesting that a specific policy be initiated for the lower echelons of MG units. Conferences, discussions, and special study projects, with occupational personnel as well as Japanese officials and citizens participating, are other important facets of the Section's work.

For purposes of military government administration, Japan is divided territorially [except as described in footnote on page 10] into two major areas--the I Corps covering the approximate northern half. Except for three special instances, in which direct command relationship is maintained, Headquarters, Eighth Army depends upon the two corps headquarters for liaison with the military government units in the field. In each corps headquarters is a Military Government Section which advises on military government affairs in the corps area. The I Corps and IX Corps commanders supervise teams on two echelons--the seven regional teams and one district team which compose the supervisory level; and the 45 prefectural teams which constitute the operating level.

Regional team commanders coordinate the activities of the prefectural teams within their areas. One exception is the Hokkaido team, which serves as the district as well as the prefectural team. Each regional team has approximately the same average personnel strength--about 65, including officers, enlisted men and civilians. The number of prefectures and the population in each regional area, however, may vary considerably--the number of prefectures from four to seven; the population from approximately 4,000,000 to 12,000,000. The specialists who head the various sections--including Legal and Government, Information, Labor, Natural Resources, Economics, Education and Public Health sections--make the rounds, giving counsel or aid to the prefectural teams. Through these specialists, the experiences and the solutions arrived at by one team are made available to all.

The brunt of military government operations is borne by the prefectural teams, one of which is stationed in each of the prefectural capitals. Members of the team work directly with Japanese officials, organizations, and the common citizenry. The teams range from 45 officers, enlisted men, and civilians in Fukui Prefecture, to the Kanagawa Prefecture team with 120, and the Tokyo Metropolis team with 80.

Military government in Japan has always been supervisory--not operational or direct. The teams do not give direct orders to the Japanese, since this prerogative may be exercised only by GHQ. Members of the team, however, do advise and suggest. The team's principal concern is to keep abreast of local conditions--political, governmental, economic, educational, and financial.

The commanding officer of the team holds frequent conferences with the governor of the prefecture and with the chairman of the assembly. The chiji-the chief executive--often calls. The conference invariably begins with a polite and hearty "Ohaio gozaimas!" or "Good morning!" and ends with an "Arigato!, Sayonara!" or "Thank you and good-bye!" The chiji reports on the Kencho (prefectural government) and explains the happenings within the prefecture. Formerly appointed, the chiji is now an elected executive, quite conscious of his responsibilities to the electorate. Pressing issues, such as rice quotas, tax collections and reconstruction are discussed. Many of the conferences are with the mayors and assembly chairmen of the cities, towns and villages. The gamut of local conditions is surveyed so that, at all times, the commanding officer knows what is going on.

In addition to the usual administrative and housekeeping sections, the teams are organized into functional sections, each with an officer in charge. Some officers have a number of functions to perform. The Legal and Government Officer, for example, not only observes the operation of the local governments and courts, but also must keep informed on political parties, and on finance and tax problems. His greatest task is to convey to the Japanese people a working knowledge of the principles of representative government. At every opportunity he explains that a citizen in a democracy has responsibilities as well as rights; that if government is to be beneficial, friendly and protective, both elected officials and individual citizens must make it so. The Japanese often ask such questions as; How do political parties work in America' How does the executive remove officials from their posts' and How has the system of recall benefited the state' Most important, they are concerned with Naze--the Why' of all principles, procedures and customs. The legal and Government Officer is kept occupied--in conferences, speeches and meetings throughout the prefecture--explaining political and governmental affairs.

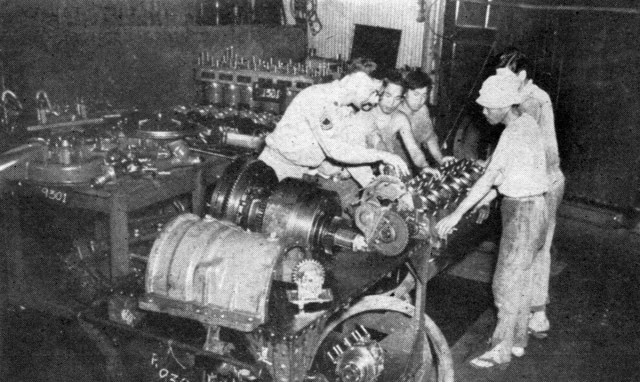

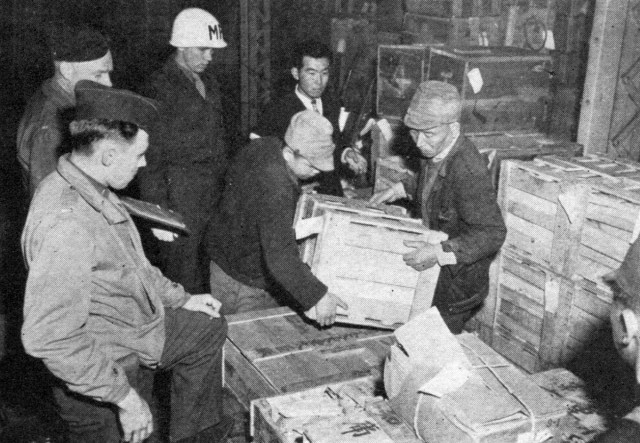

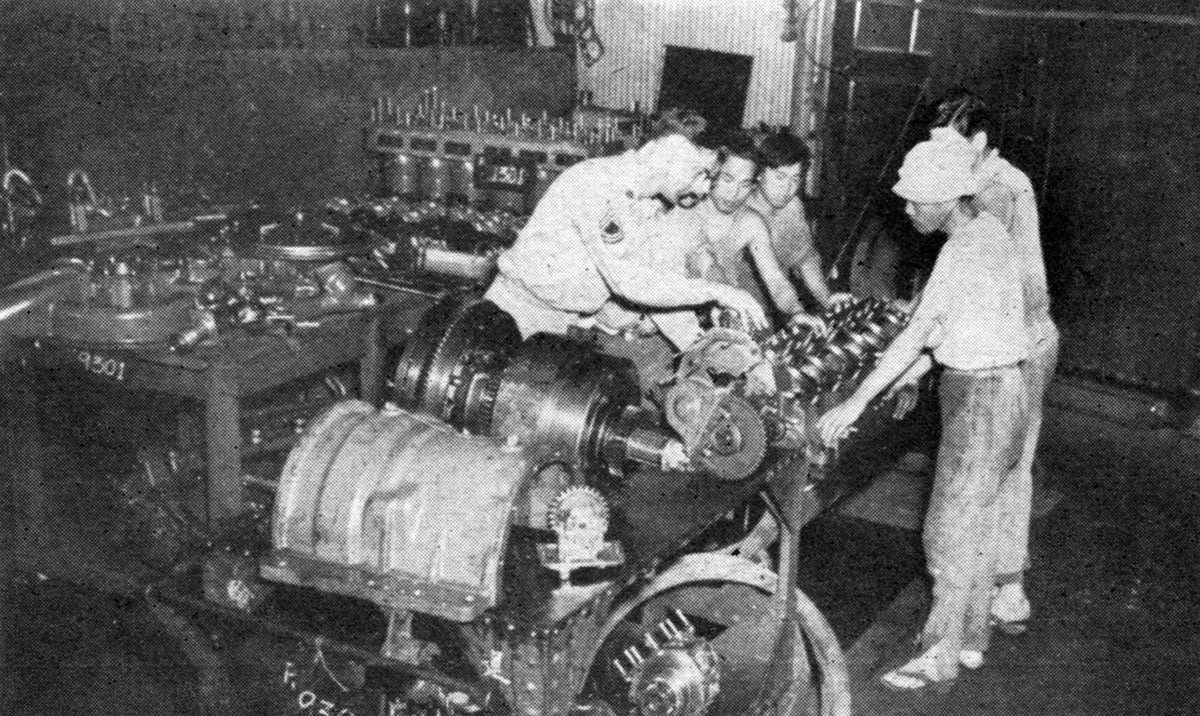

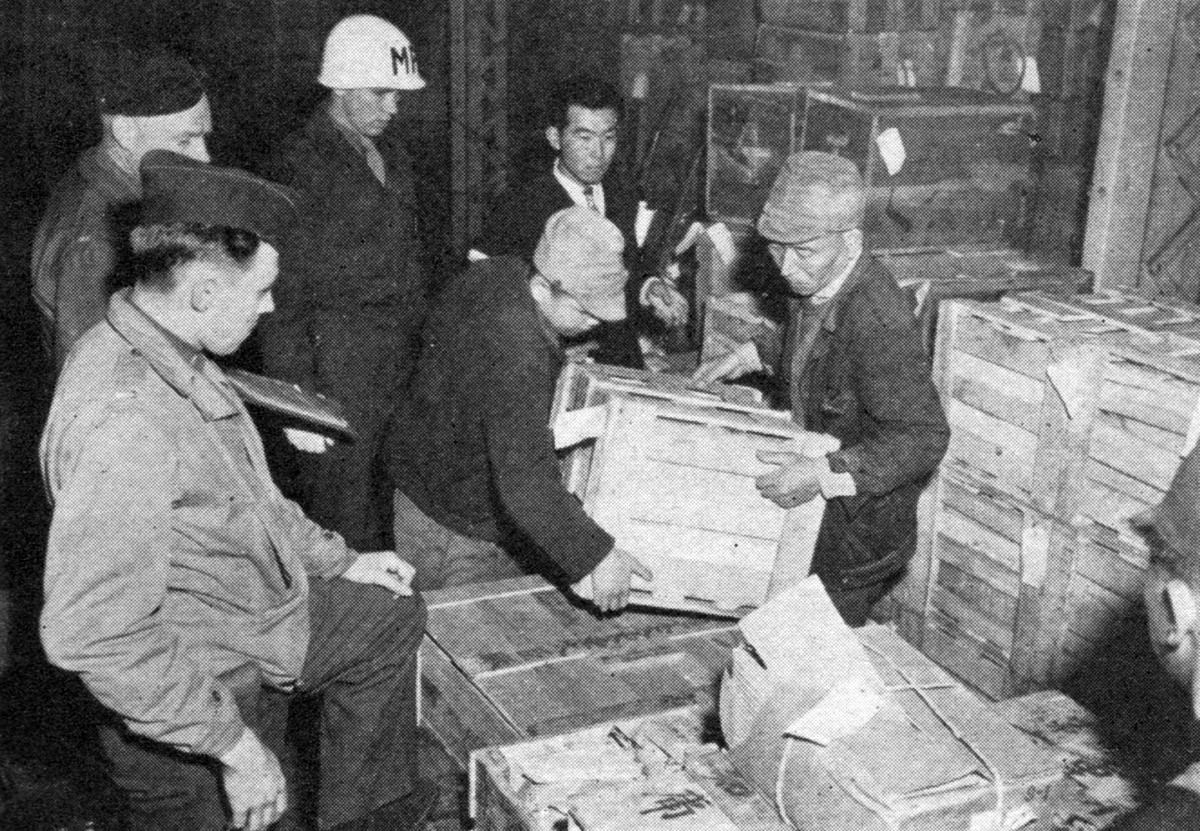

The Economics Officer--on the end of the long chain of responsibility--is concerned with vitalizing the Japanese economy, so as to achieve as rapid rehabilitation as possible. Today he may be engaged in overseeing the inventory of the industrial plants in the prefecture. Tomorrow, under direction, he may be inspecting an electric power plant, a steel mill, or a shipyard, to discover means of stepping up production. The next day he may be observing conditions in the fishing industry or otherwise helping to overcome local food shortages.

The Labor Officer has an important task--the development of healthy, objective-type labor unions,k and the fostering of harmonious labor-management relations. The Public health Officer maintains close surveillance over measures for the control of disease and epidemics. He supervises the carrying out of SCAP directives, and aids and advises Japanese public health and sanitation personnel.

The Education Officer is engrossed in the whole field of Japanese education, as it is affected by the SCAPINS and the new las passed by the Diet. The removal of elements that fostered ultra-nationalism and aggressive militarism is one of his continuing tasks. He seeks to stimulate citizen interest in educational issues. He encourages community interest in the local school board, the selection of teachers and subject matter, school building construction, and the morale in the educational system.

The Information Officer, the Economics (Agriculture) Officer, and the Welfare Officer travel through the remote byways of the prefecture, following with indefatigable patience and understanding the daily problems of the farmers, the fishermen, the poor and the needy.

Today, in the fourth year of the Occupation--with the beginning of democratic tendencies established among the Japanese people--strides are being made toward the goals set forth by the Allied nations in the Potsdam Declaration. Civilians--a term entirely new in Japan--no longer are treated as subjects en masse. Japanese officials, accountable at last to the electorate for their actions, daily are taking new steps "in the public interest." On every level, the military government teams foster the growth of self-reliance, both in private and in governmental agencies. The feudalistic trek to Tokyo for the only proverbial all-wise answer is a diminishing phenomenon. The effects of a hundred decades of regimentation are being loosened. The Japanese are being encouraged to do this themselves, gradually.

While outside the orbit of the Occupation there are great ideological clashes, throughout the country the military government teams proceed with their day-to-day tasks--the surveillance of adherence to SCAP policy. In doing so, they are nourishing the grass roots of a re-growth of Japan along democratic lines.

Social Sharing