"You're a brave woman," the clerk in the travel bureau in Colorado told me, with a disapproving stare that said "You're a foolish one." The news that I was on my way to Tokyo with my three children, one of them a 22-months-old baby, was raising that kind of comment all the way from Galveston, Texas, to Seattle, Washington, where we expected to board the ship for Yokohama.

"I don't care how much I loved my husband, I wouldn't follow him to a heathen country like Japan!" the lady bus driver in Galveston had announced stoutly. She considered me a most inhuman mother to permit the Army doctors to give Cecil Jr. the dozen or more necessary inoculation and vaccinations. As a matter of fact, Cecil Jr., himself, didn't mind nearly as much as she did. He was not sick from any of them, although the 11-year-old twins, especially Barbara, stayed in bed a day or two after the typhoid and tetanus shots.

It would have been a treat to visit my family in Waterbury, Connecticut, before leaving the States; but they, too, were fearful about my going, and I didn't want those for well-settled sister to overwhelm and dissuade me.

We stayed three days at Hostess House, Fort Lawton, Seattle, the Army port of embarkation--840 Army wives and children, waiting for the Matson luxury liner 'Monterey.' What a flurry of excitement and anxiety each day in the dining room, central clearing house for rumors!

"I hear there's going to be no meat, butter, or eggs over there."

"What will my baby do without his orange juice'"

"The Japs are likely to take pot shots at us from dark buildings..."

But I remembered that meat, butter, and eggs were none too plentiful right at home; remembered too, that during my husband's 25 years of service, the Army has always taken good care of us. Contrary to the opinion of my friend the bus driver, I think that if a woman loves her husband enough she'll follow him almost anywhere.

The Monterey is a beautiful ship. A USO troupe gave us a hearty send-off, which we appreciated the more because we had no families to wave to us from the dock. The nine-day trip was a fine one, despite cold weather and several days of rough seas. We were pretty crowded, but the accommodations were good, the food excellent.

The children enjoyed themselves and one another. My Robert, one of the twins, scanned the sea with his binoculars and reported every school of flying fish sailing into the Westerlies. A light flickering on the horizon on the eighth night cause great excitement, but it proved to be only the signal of a passing ship.

We were up the next morning at 0400, and the first Japanese sight we saw was a bobbing boat with a Japanese fisherman in it. Later, above the low brown and green islands forming among the clouds, we caught a glimpse of Mt. Fuji. Like other adored beauties, Japan's sacred mountain doesn't show herself to all, but usually hides coyly behind a veil of clouds. Now there were dozens of fishing boats and barges around us, large and small, trailing circles of gray-winged scavenger kites.

The real sight, though, was waiting for us on the Yokohama pier. Children crowded the rails to recognize dads they hadn't seen for a year or two. Army transports greeted us with music and flowers. There was a good deal of laughing and shouting, and a little bit of crying by babies, and by people old enough to know better.

Let me confess that after the first thrill of being with my husband again, I looked around and, for the first time since deciding to come to Japan, wondered if my decision had been a wise one. A Japanese girl in western dress came up to talk with me as we stood waiting for Cecil to bring the jeep from its parking space down the road.

"And you're from America," she said with eyes that burned brightly. "Ah madam, you won't like it here!"

During that ride from Yokohama to Tokyo, I viewed with tired eyes the devastation of war; the surrounding miles of blasted buildings, rubble piles, and flattened ruins. Pointing out the rusted-tin and scrap-lumber shacks built on the former sites of factories, the neat vegetable gardens boasting lean corn stalks and rambling squash vines, Cecil assured me that Japan had made great strides toward recovery in the last year.

"You should have seen this place last December," he said.

"We folks back in the States," I told myself, "have had nothing to complain about."

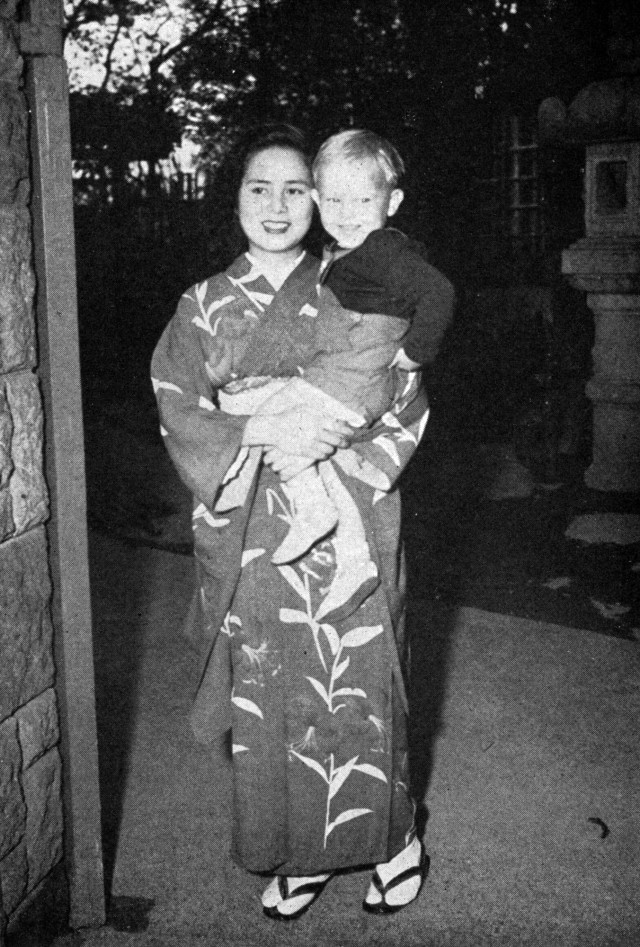

Our children and the Japanese goggled at one another. Blond youngsters are still a novelty in Japan. I scrutinized the woman in kimonos with their babies on their backs. I had long since vowed that no Japanese girl would lay hands on my own baby.

As Cecil drove us through the narrow streets of outer Tokyo, I tried to picture what kind of a shack we would call our own. The jeep pulled up in front of a western-style, two-story frame house with a garden wall--a house with gracious old trees, a yard friendly in shrubs and flowers. It might have been in Waterbury, Connecticut, but for a large, Japanese stone lantern in the back yard. In my letters to Cecil I had asked about our house and he had never termed it better than "not bad." Now he waited for my appraisal.

"Do you mean to tell me that we will live here!" I questioned dubiously.

"This is our home," he said.

Our four servants came to meet us with many smiles and bows. They had decorated the house with flowers. And what a house! Stateside friends had urged me to carry with me as much kitchen equipment, linen, and furniture as was permitted, but I had followed Cecil's advice and brought almost nothing except clothing, and with some misgivings too.

To my amazement I found a home ready to live in; a kitchen complete with electric stove and electric refrigerator, toaster, waffle iron, coffee peculator, dishes, silver ware, table linen, and even curtains on the windows; two bathrooms, one with a tile bathtub; four bedrooms, one of them Japanese style, which Babs adores. It has the Japanese straw mats on the floor, sliding doors, and a special shelf for ceremonial dolls, which she has already begun to collect.

There are several stained glass windows in the living room, parquet hardwood floors, a telephone, and all the necessary furniture. Workmen are installing pipes for gas heat. We need a rug for the dining room, and I shall probably replace some of the drapes when my sewing machine arrives; but those are details that can easily be taken care of. It has been a delightful surprise, finding a home like this six thousand miles across the sea.

Ours is not the finest home in Tokyo, nor is it the most modest. Some of our friends live in 18-room villas requisitioned from the local tycoons; others in Quonset huts or small apartments. The Army has been working feverishly, Cecil tells me, to put dependents' housing in readiness for the families coming over; but the job is not finished. The Quonsets are a temporary accommodation. In a matter of months, every family here should have a separate home if it wants one.

As in the case of other Army allotments, living quarters are assigned on the basis of seniority, rank, and the number of family members. My husband's 25 years of service and our three children were important factors in obtaining so attractive a home.

The shortage of meat in the United States will be felt here in Japan, too; but those Army wives in Texas who have been standing in long lines for their meat every week or so, when there's any to be had, should know that over here we campaign against waste; there will be less meat for snack bars and parties, but personnel will continue to find a sufficiency on the dinner table. We have had all the butter and eggs we want, too; in fact, our food in general has been excellent. Cecil often brings home oranges and apples from the commissary. We have fresh cabbage, often lettuce and celery, onions and other fresh vegetables, in addition to a wide variety of fresh frozen vegetables. Fresh milk goes to patients in Army hospitals, but my children drink their canned milk flavored with a little chocolate syrup and don't mind; although thus far they have turned up their noses at powdered milk.

I found to my disappointment, soon after moving into my home, that there are no other American families in the neighborhood. This as not good news to someone who enjoys a little over-the-fence gossiping now and then, and I felt I might be lonely. I walked around the Swiss Legation nearby, but met nobody.

To those folks back home, however, who dreaded to come over and live among the Japanese, I'd like to say, "You have nothing to fear." The Japanese people are trying with all their hearts to be courteous and friendly. Our neighbors have all introduced themselves to us, again with many bows and smiles, and have brought presents, and helped us get comfortably settled . I had a long talk the other day with a Japanese boy who lives in the house next door, a 13-year-old (14, by the Japanese reckoning) who is studying English and who needed my help in translating some words in his American comic book.

After a few exploratory questions, he told me, "I would like Bobby for a friend. Do you think he like be my friend'"

I pointed out that Bobby, being a boy, enjoyed many outdoor sports like baseball and soccer, and that if Hishashi would come over and get acquainted, I thought they could enjoy those games together.

The Japanese are eager and able students of the English language. Few well-educated Japanese are unable to speak at least a little of it. It's a required subject in school. All the larger stores, hotels, and travel agencies have English-speaking clerks. Children in the streets are picking it up fast from American troops. I'm pretty sure Japan will learn English long before we gain any proficiency in Japanese.

When I found how competently the nursemaid took care of Cecil Jr. and the immediate affection he showed her, I changed my mind about giving him into her hands. Japanese women are wonderful with children.

The twins will find nice friends at the American School for Dependents, a ten minute bus ride from our home. The campus had been used before the war by a private school for American and other foreign children--charming, old, ivy-covered brick buildings, a good library, a gymnasium, and a science lab. The teachers are Army wives who have teaching credentials. The school bus goes right by our corner. The twins have a good, hot lunch there every day, with milk and a dessert. They're particular about their food, and they tell us they enjoy the meals they're getting. They're in seventh grade and taking arithmetic, history, English, and geography. Japanese will be offered soon, because almost all student are eager to learn the language.

Cecil tells me that the Tokyo Army Educational Center, and Eighth Army school, has a wide selection of afternoon and evening classes on the high school and college level. I'd like to take Japanese, myself.

Being accustomed to the mild winter of Galveston, we will probably feel the cold here in Japan. The weather men predict a long, hard winter. We came with a goodly supply of clothing, but the baby grows out of his clothing so rapidly that I hope the new Eighth Army department store, opening this month in Tokyo, will carry a line of baby clothes. The twins will need new outfits, too, especially shoes.

Housewives in the States warned me that cotton would be a scarce item in Japan; but, again following my husband's advice, I brought none with me. I'm glad, because the cottons I find in the Army exchange are nicer than many we fought for over the counters back in the States; and they cost 20 and 30 cents a yard, instead of 79 and 89 cents for the cheapest at home. When my dewing machine arrives, I can make gay, pretty things. Silk merchandise, including stocking, are also easy to find. We have a nylon ration of a pair a month, too.

One of the comforts of home that I certainly did not expect to find over here is the beauty parlor. There's a first-rate one in the Tokyo exchange, which I visit regularly. There are others in some of the women's billets around town. The operators are trained in giving not only shampoos, cuttings, and waves, but also permanents.

My sisters write that they must make their dental appointments a month in advance; our old family doctor is run ragged with too many patients. It's satisfying to know that here in Tokyo, in case of an emergency, there's a doctor as near as our telephone. Medical and dental care is readily available to us all. Army hospitals throughout Japan have made special preparations to care for dependents, including wards for children. A few American babies have already been born in Japan.

Sooner or later we will have a GHQ Army chapel in the center of town, a nondenominational religious center where Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish services can be held; and religious training will be provided for Allied children. In the meantime, services are held in the various office buildings and billets. We find that the 1100 Catholic Mass at the Dai Ichi Building on Sunday mornings is quite handy. The twins have specified on a questionnaire that they would like to receive religious training at school.

The Dai Ichi Building, headquarters of General MacArthur, is, by the way, an example of the new Japan--a beautiful, modern structure with all the conveniences, including air conditioning. This is a land of great contrast--sod-roofed huts and western palaces; ox carts and wooden scandals clattering over cobblestoned streets among honking jeeps and limousines.

Our family jeep will take us to tourist spots old-timers tell us about--Kyoto, the ancient capital city with its shrines and palaces; Nikko, Atami, Ito, and the other resort towns, some of which are famous for hot mineral baths. I'd like to see Karuisawa, the international village up in the Japanese Alps, and more of the Japanese countryside, with the colored maples in the fall and the cherry blossoms in the spring. One can go to all these places by Japanese trains, which are pleasanter than you might imagine, since there are special cars for military personnel and pullmans for overnight trips.

Honestly, I don't expect to become bored. There's a tennis court nearby, and I love tennis. We'll need some daily exercise at the rate our clothes are tightening over here. We're enthusiastic movie-goers. My husband's office has frequent dinner parties and dances. Next summer it will be fun to go swimming at the Shiba park swimming pool close by. The entertainment in the field of art and drama is outstanding. In addition to occasional Japanese plays like the Noh and Kabuki, festivals and dances, we enjoy concerts of western music. We frequently go to Hibiya Hall, the Ernie Pyle Theater, and the Tokyo Army Educational Center, where we hear American, European, and Japanese artists; and where we see Special Services theatrical productions like Night Must Fall, Arsenic and Old Lace, and The Drunkard.

In the States, the household affairs and care of my children kept me on the job all day long and often left me too worn out for much activity in the evening. This is a vacation. I feel like a lady of leisure. I'm actually more rested and happier than I was back home, and I have more time to enjoy my husband and children. To other Army wives still undecided about making this trip, I'd like to say, "Hesitate no longer."

Social Sharing