The Soldier on occupation duty in Kyushu is first of all a fighting-man. The major portion of his time is given to a rigorous training schedule. But, once his training day is over, he finds a variety of facilities for pleasant living. he is quartered in comfortable barracks, eats good American food in well-equipped dining halls, attends church services in attractive chapels, sees the latest American films, tunes in daily news broadcasts from the States, purchases at a well-stocked post exchange, participates in leisure-time activities at Red Cross clubs, and engages in competitive sports. Except for differences in climate and geography, he moves in an orbit of garrison life similar to that in the States.

Activities in a typical occupation force--the 24th "Victory" Division--reflect the mode of life of the American combat Soldier in Japan. After fighting throughout the Pacific, the 24th Infantry Division (comprising the 19th, 21st, and 34th regiments and Division Artillery) landed in Japan as part of the original occupation force in October 1945. From Shikoku, smallest of the Japanese home islands, the DIvision moved to Honshu, and finally, in June 1946, to Kyushu, where it is the tactical occupation force.

Kyushu, the most southerly and scenic of the four Japanese home islands, has a population of about ten million people. It is best known because of atom-bombed Nagasaki, its largest city and chief port. The island is primarily agricultural; but the far northern sector abounds in coal and is highly industrialized; Kokura, headquarters city of the Division, is also the site of the Yawata steel mills, largest in Japan.

The Division's 19th Infantry is based at newly built Camp Chickamunga, on a thickly wooded slope near Beppu on the east coast. To house the 21st Infantry, existing Japanese buildings were improved and many new ones were built at Camp Wood, near Kumamoto in Central Kyushu. The 34th Infantry is comfortably settled in new and renovated buildings at Camp Mower, near Sasebo on the west coast. Division Artillery is located at Camp Hakata, on a peninsula extending into the Genkai Sea, in picturesque northeast Kyushu. Close liaison is maintained with Military Government, the Counter Intelligence Corps and the Criminal Investigation Division, and the Division stands ready at all times to fulfill its tactical occupation mission.

No mater which organization picks him up on the morning report, the 24th Division Soldier feels the all-pervasive influence of the Division training program. The greater portion of the Division's enlisted men are 18-month enlistees, many of whom came to Japan in late 1946 and early 1947 with a bare eight weeks of basic training, and in some cases as little as four. While their arrival bolstered the ranks of the depleted occupation forces and bought the Division to full strength, it also posed the problem of additional training.

New arrivals are briefed in the history of the Division, and are early imbued with the traditions and prestige of their outfit. Basically trained, and conditioned by marches, bivouacs, and combat problems--in which unites use live ammunition and advance on terrain objectives--the recruit gets a thorough training in the numerous subjects the infantryman and artilleryman must know. Most of his officers and non-commissioned officers have had combat experience, which they apply in training operations over the Kyushu countryside. In spirited competition with other units, the recruits vie to achieve the highest scores in training tests.

Trade training in needed specialties is provided for enlisted men. Qualified Soldiers attend the Division School Center, at Kokura, for training as radio operators, cooks and bakers, clerk-typists, or as armorer-artificers. Higher echelon schools are open for advanced training in welding, mechanics, and numerous other fields.

The Soldier seeking to broaden his formal education is encouraged to enroll in a variety of off-duty classes held in school buildings within the battalion areas. Or he may enroll in a wide range of correspondence and self-study courses offered by the United States Armed Forces Institute. Thousands of 24th Division men are participating in the education program, many of them earning high school and college credits. Well-stocked Army libraries, staffed by experienced librarians, aid the education program. Books on a wide variety of subjects are available, as well as magazines and periodicals, many less than a month old.

The Soldier's understanding of his occupation mission is stimulated in the Troop Information Hour, conducted weekly as part of the training requirement. Group discussions are held on world affairs and occupation problems, including proper attitudes and behavior in dealing with the Japanese people.

Normally, the Soldier in Kyushu has little direct communication with the Japanese. While he sees them on every hand, mingles with them on the street, and may haggle with a merchant in a rudimentary language of gestures and catch-phrases, the language is always a formidable barrier. The natives of Kyushu are generally cooperative, and with few exceptions are eager to do what they can to assure the success of the occupation. Many recognize that the occupation Soldier is here to assure that the peace and democratization of Japan become a reality; and most of the natives seems fairly happy about it. The natives bow when spoken to; and the few who know English come forward with alacrity to engage in conversation. It is not uncommon to see and American Soldier bow and say a word of greeting to an older Japanese who will return the bow and seem greatly pleased at having been recognized. As everywhere, children and Soldiers find a common language in games and in exchange of greetings.

Dining halls are comfortable and attractive. Tablecloths cover the dinette-size tables, and curtains adorn the windows. Rations are plentiful, and food is of the same quality as that back home. Only fresh milk is noticeably lacking. There is little waste in the mess, for the Soldier in Kyushu has seen too many instances of hunger among the Japanese to be careless about food. Living quarters are well-lighted and airy. Dormitories are stem-heated, with plenty of hot water for showers. Laundry service is on a three-day basis.

Unless he is careless, the average Soldier in Kyushu can save a substantial portion of his pay. Necessities can be purchased at low prices in Army exchanges. A rationing system assures each man an adequate supply. Each week the Soldier may purchase a bar of soap; a tube of shaving cream or tooth paste; a supply of tax-free cigarettes; six bars of candy; and three packs of gum. Tobacco and cigars are off the ration list, and may be purchased in any reasonable amount. For the souvenir-minded Soldier, the post exchanges carry an ample stock of Japanese goods. However, if he does wish to purchase at inflationary levels on the open market, he can exchange his Army pay for Japanese yen. Because of the seriousness of the Japanese food situation, Soldiers are not permitted to patronize Japanese eating places.

Motion pictures and radio broadcasts provide a touch of home. The Armed Forces Radio Service Station WLKH at Kokura beams a variety of radio shows to squad rooms, day rooms, and service clubs. Outstanding programs heard in the States are rebroadcast by transcription. Every day six news programs from the United States are picked up and rebroadcast. Unit newspapers also maintain group esprit.

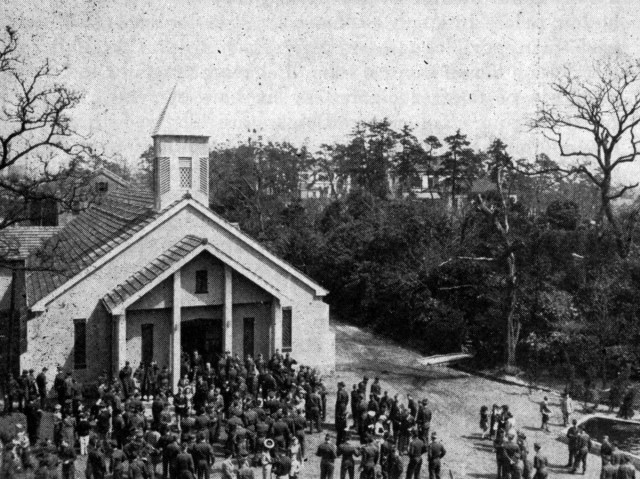

American Red Cross clubs, staffed by girls from home, offer a full program of entertainment. Some have hobby and handicraft shops, photographic darkrooms, and game rooms. Among Soldiers who are young, impressionable, and far from home, the need for leadership and spiritual guidance is ever present. By developing competitive team spirit--in achieving the neatest area, the best mess, the highest scores in training tests, and the highest level of sportsmanship in athletics--officers and noncommissioned officers are instilling a sense of group responsibility that carries over into the field of individual values. By personal guidance and religious instruction, 24th Division chaplains are direction the Soldier's innate idealism into constructive activities. Religious services in all creeds, held in attractive chapels, are widely attended.

Physical stamina and team spirit are developed by the Division's well-rounded sports program. Competition extends to companies, batteries, and oftentimes to squad level. There is a sport to interest every man, and virtually every man participates. Each unit sends its best men to try for the "Big Green" All-Division teams. Soldiers who make an All-Division team travel widely and compete with the other teams that compose the American League of Japan. Experts in individual sports, such as golf, tennis, or track, may qualify for the All-Japan team which competes in inter-command events with the Korean, the Philippines-Ryukyus Command, and others.

Families of first three graders are arriving in increasing numbers. Comfortably furnished homes in well-planned housing areas have been built for them. Some Army families have brought their cars, and though the countryside is mountainous and roads are notoriously bad, these civilian vehicles help solve the local transportation problem. Train service, on the other hand, is excellent; and, whether on duty of leave, the Soldier rides free. Berths are smaller and more cramped than their Stateside counterpart, but the compartment cars are commodious and comfortable. The Dixie Limited, Allied Limited, and other fast express trains, provide service comparable to that in the United States. The always-crowded civilian trains which link important Japanese cities have special cars reserved for Allied military personnel and Army Department employees.

Japan is a photographer's paradise, abounding in scenic and historic places. The Shinto torii--a distinctive two-pillared gateway with crosspieces superimposed--has framed many a prized photograph. Most Japanese shrines are off limits, but some ancient temples and places of worship are open to conducted tours and visits. A famous Buddha near Beppu is a favorite subject for photographic devotees.

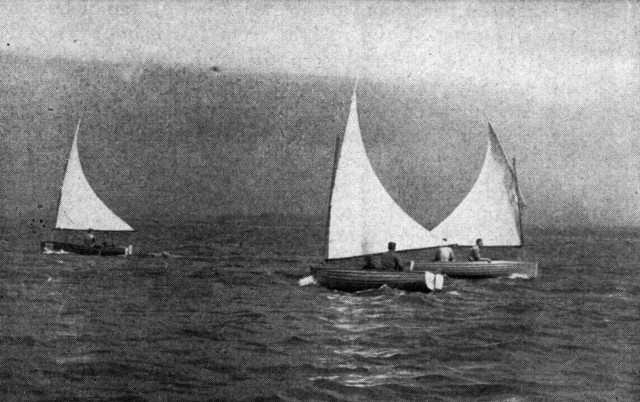

At beach and boating areas near Division installations, miniature resorts have sprung up. Here Soldiers swim and go boating. In summertime, holiday regattas are held. The men sail their own dinghies or indulge in racing and pleasure cruises.

Periodically, the occupation Soldier takes off on pass or leave for a vacation at one of the Army leave centers. Several of the finest Japanese hotels and resorts have been taken over as places to swim, golf, ride, or just relax. Quotas are filled by Army units from among men who are eligible for leave. In certain resorts, Japanese customs are followed. The men remove their shoes at the door, and sleep on soft quits on the straw-mat floor. A hard, straw-filled makura serves as a pillow; and the room is warmed by a charcoal-burning brazier, or hibachi. Well-trained Japanese maids and houseboys serve food in native style, adding a quaint touch to a memorable interlude of relaxation.

It's not a bad life--that of the Soldier in Kyushu.

Social Sharing