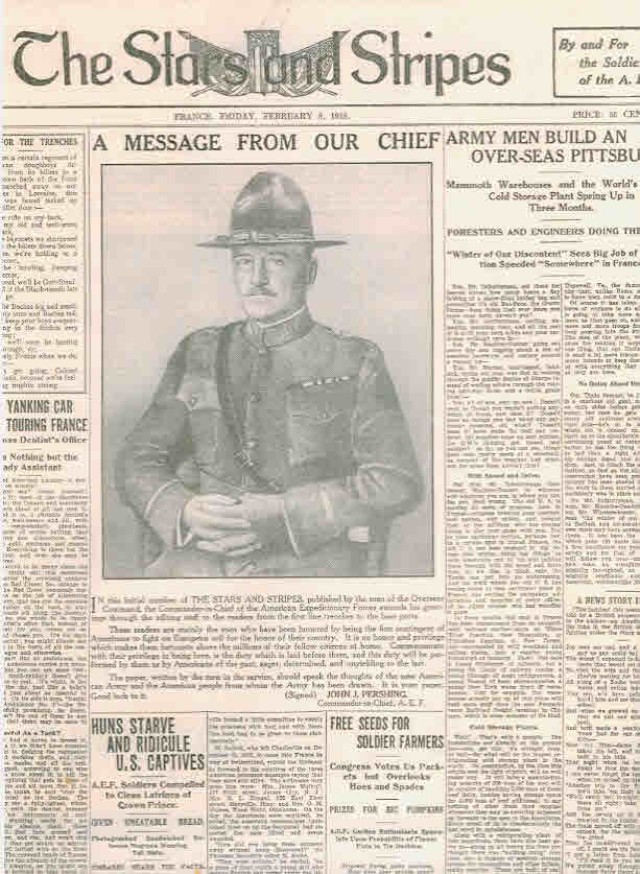

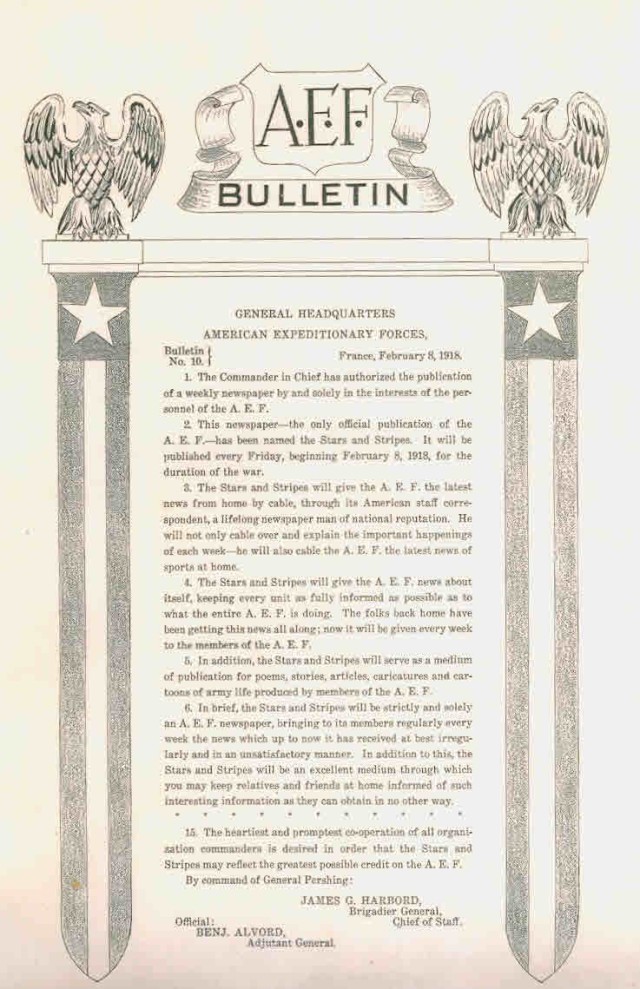

The week of September 20, 1918, saw the thirty-third issue of the Stars & Stripes fresh off the presses. During and immediately after World War I, there would be a total of seventy-one weekly issues printed, from February 8, 1918, to June 13, 1919. The United States Army published the newspaper for its Soldiers in France by order of General John J. Pershing. American Expeditionary Forces Bulletin No. 10, issued in France on February 8, 1918, stated in part: "1. The Commander in Chief has authorized the publication of a weekly newspaper by and solely in the interests of the personnel of the A.E.F. 2. This newspaper - the only official publication of the A.E.F. - has been named the Stars and Stripes. It will be published every Friday, beginning February 8, 1918, for the duration of the war. 4. The Stars and Stripes will give the A.E.F. news about itself, keeping every unit as fully informed as possible as to what the entire A.E.F. is doing."

The first managing editor of the Stars and Stripes was Second Lieutenant Guy Viskniskki, an A.E.F. press officer. Viskniskki\'s original staff members were enlisted soldiers, some having had prior newspaper experience. Among the staff were Privates Harold Ross (who would later become a co-founder of the New Yorker magazine), Hudson Hawley, and John Winterich, and Sergeant Alexander Woollcott. The weekly Stars and Stripes was eight pages long and consisted of correspondence, editorials, sports, poetry, cartoons, illustrations, and advertisements. Soldiers were eager to know what was going on at home and not just on the front lines.

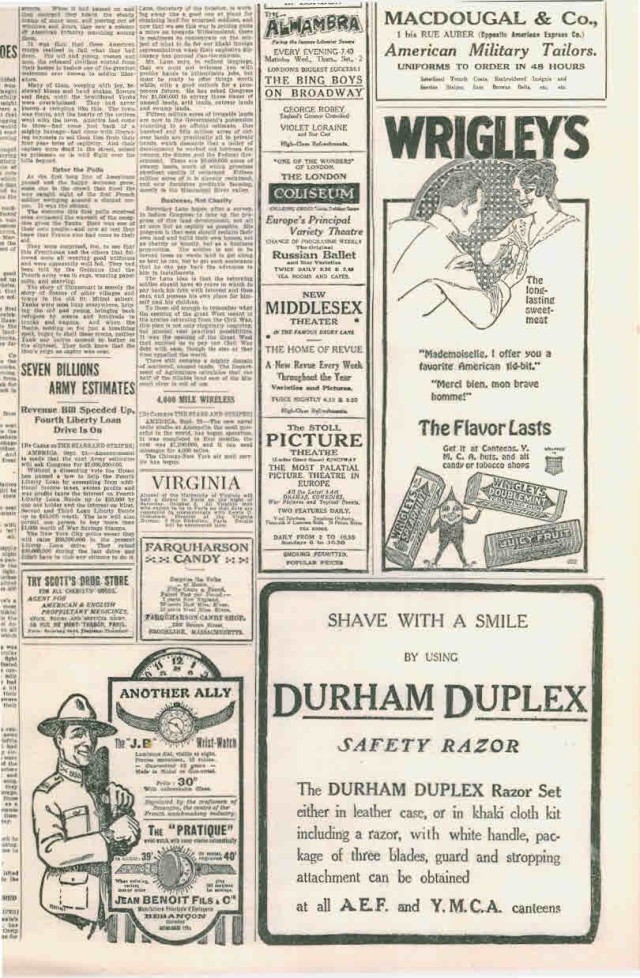

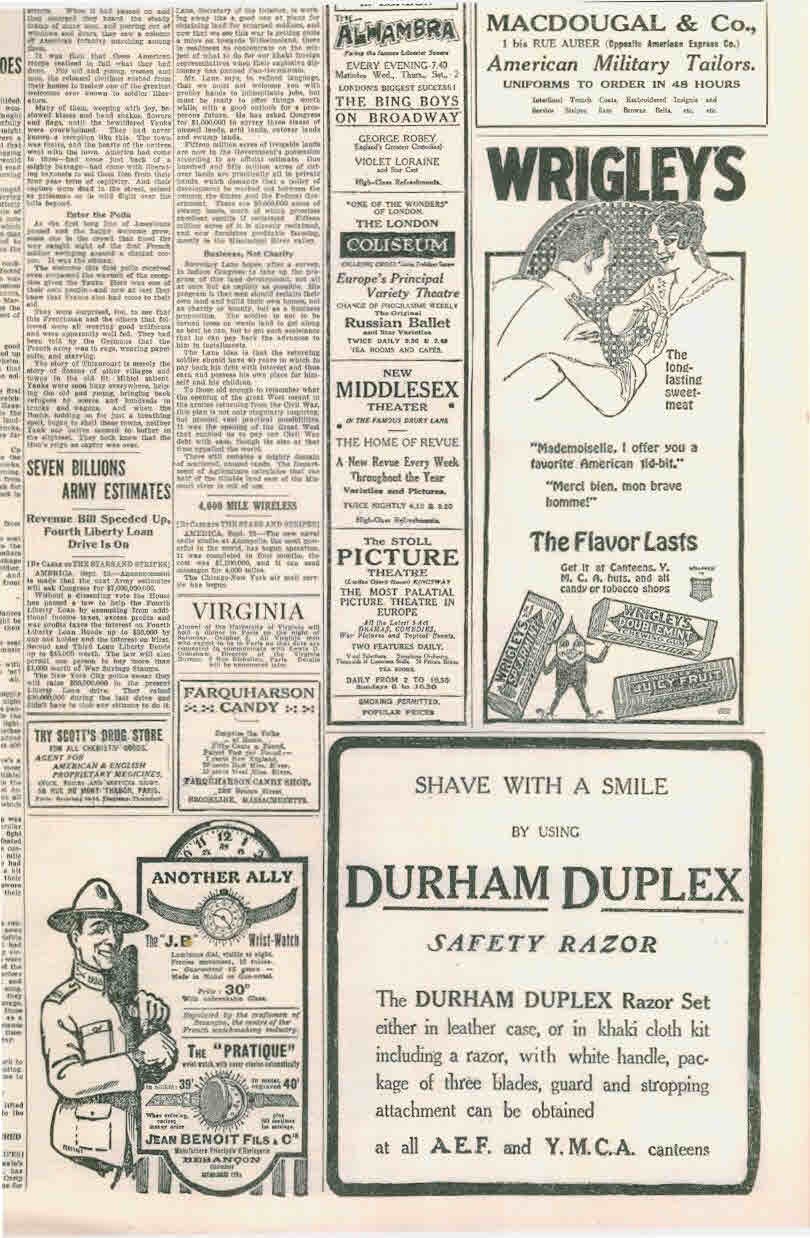

A thorough look at the September 20, 1918, issue gives insight into what a soldier could expect: There were no less than sixty advertisements, selling everything from razors, chewing gum, clothing, shoes, books, recreational tours, hotel accommodations, and even the best sardines. There were seven poems, such as the melancholy "To a Doughboy:" "I watched you slog down a dusty pike/ one of many so much alike/with a spirit keen as a breath of flame...." During the run of the Stars and Stripes, soldiers would ultimately submit more than 75,000 poems.

A favorite cartoon among the troops was called "Helpful Hints" and in the September 20 1918, issue, it was entitled "To the Committee on Uniforms," a farcical look at military dress. Another cartoon was called "It's Easy if You Get Sore," a not so funny depiction of an American soldier hiding from a German sniper. There were also illustrations, such as the celebratory "The Boche Have Gone,"' representing a French woman speaking with two American Soldiers among the ruins of the destroyed village around her. The official sports page was cancelled with the July 26, 1918, issue. The paper's editorial board stated "This is the last sporting page the Stars and Stripes will print until an allied victory brings back peace....there is but one big league today for this paper to cover...." Even minus a sports page, there was a short editorial in the September 20 edition titled "For the Good of Baseball" hoping that those who played in the 1918 World Series "will have salted their season's profits and joined the army."

The majority of the print was taken up with war stories from the field with particular emphasis in the September 20, 1918 issue on the recent American victory in the St. Mihiel Salient. An interesting side-note was an official bulletin by the Chief Surgeon, Brigadier General Merritte Weber Ireland, A.E.F., banning the word "shell-shock" as a diagnosis. There were seven editorials from Soldiers in the field and civilians back home. One piece from Ottumwa, Iowa, went like this: "Having received copies of the Stars and Stripes from our dear daddy in France, how jolly well our brave boys must appreciate reading this paper...." In World War I, censorship played a role for the first time in American history. Stars and Stripes reporters were required to have stories cleared by the Army Board of Control and Military Intelligence Service before being released to the general public.

The First World War edition of Stars and Stripes ended its run on June 13, 1919. A lengthy front-page article best summed up the paper's mission: "Yanks' own paper was for the enlisted man first, last and all the time- goodbye!" Today's Stars and Stripes continues to inform the troops as did its predecessor. The paper's editorial staff delivers the news in print, electronic, digital, and streaming video format. Its mission today is very similar to what it was in 1918. The "Stars and Stripes exists to provide independent news and information to the U.S. military community."

Social Sharing