PRESIDIO OF MONTEREY, Calif. Aca,!A? The Army Health Promotion, Risk Reduction, Suicide Prevention Report for 2010, published June 29, is as candid as it is lengthy.

The message of the report is apparent: War has taken a toll on good discipline and Soldier resilience. Soldiers are engaging in more high-risk behaviors, many of which are tied to drug and alcohol abuse. Crime is up. Last year, more Soldiers died from their own high-risk behaviors than died in combat. Commanders are missing key opportunities to refer or separate individuals who are not meeting Army standards of conduct.

What does this have to do with suicide'

Quite a lot, in fact.

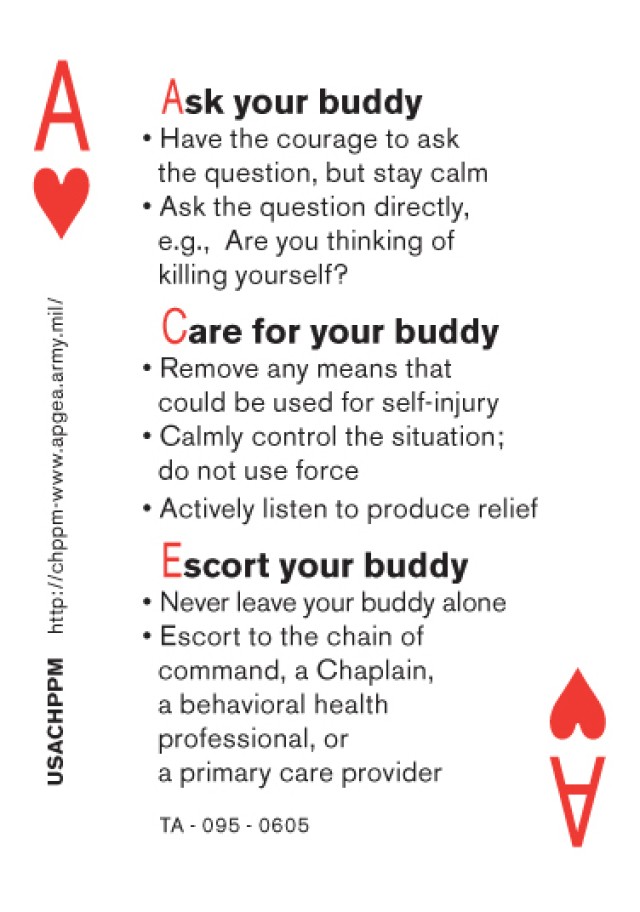

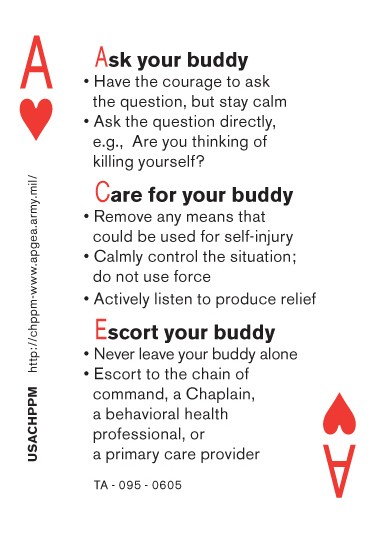

Suicide prevention efforts have historically been narrowly focused. Intervention training has taught people to address obvious signs of suicidal intent, to not let phrases like "things would be better off without me" go unchallenged, to talk to buddies and colleagues when they seem depressed. There is great merit to these recommendations, because they encourage communication, emotional openness, and that bit of intrepid nosiness that can - and does - save lives.

However, as this latest report indicates, the relationship between stress, high-risk behavior, and suicide can no longer be ignored. Life events lead to stress. Unmitigated stress can lead individuals to seek relief through high-risk behaviors like drinking, intentional self-harm, gambling, drug use and criminal recklessness. High-risk behaviors can alter the mind, damage the body, tarnish the self-esteem, and compound feelings of hopelessness and desperation. Suicide can be the tragic result.

Suicide can seem to be borne from unlikely situations, and it can occur in unlikely individuals. Survivors may say, "We never saw it coming," and they may be correct.

But perhaps this is because people are not seeing the larger picture. Perhaps they don't interpret an act of insubordination as a cry for help. Perhaps they look at a buddy's drinking antics as a source of amusement instead of a sign that he might be self-medicating. Perhaps they feel they don't have time as leaders to sit down with every service member or every employee on a regular basis to take their emotional and psychological temperature, if indeed supervisors even feel qualified to do so. Perhaps people are just not sure what they can do to help.

The truth is that these oversights and concerns are not uncommon, nor are they completely unwarranted. It can be difficult to approach friends when we think they might have a problem, and it can be even more difficult to talk to those who we don't know very well at all.

It takes great courage to tell a colleague they might benefit from seeking help, and it can be downright counterintuitive to look at a UCMJ violation and see something more profound than irresponsibility.

But in our uneasiness we also have to ask ourselves this: Is our discomfort worth the potential human price' Might that missed opportunity become another harrowing, preventable statistic'

The good news is that there are many ways for people to be better helpers. One need not cold-call every individual on the personnel roster to ask if they are thinking of suicide.

Suicide prevention starts with stress management, addressing problems and stressors before they become crises. In this broader sense, suicide prevention is sometimes as easy as asking a friend to join us for a fun fitness class at the Price Fitness Center. It could be as simple looking a coworker in the eye and genuinely making them feel valued. It could mean slipping someone a flier for a chapel-sponsored couples' retreat when we know things aren't going well at home.

The more serious side of this is knowing when to set aside fears - even fears of losing friendships - in order to potentially save a life.

Reporting a buddy or coworker to the chain of command because of suspicious behavior or concern for their emotional stability can be excruciating. It can feel like betrayal, and it can make people second-guess their loyalty to comrades and colleagues.

But in this military family, doing the right thing sometimes means doing the hard thing. A referral to ASAP or behavioral health can be positively life-altering. A visit to Army Community Service for financial assistance or an anger management class can lead to tremendous relief. The right word on the right day from the right person can mean everything.

"Shoulder to Shoulder" is more than just a catch phrase for the Army's Suicide Prevention Program.

It means that people have to look out for each other every day, in theater and in garrison, at work and at play. It means standing up for each other and wearing our concern openly. It sometimes means being the bad guy.

People should all feel empowered, because suicide prevention is a community effort, and there is an irreplaceable place for everybody. You are irreplaceable. We all are. Together, shoulder to shoulder, we do not stand alone.

This year's National Suicide Prevention Week is celebrated Sept. 5-11. For information about Presidio of Monterey suicide prevention workshops and resources, contact Whitney Bliss at the Army Substance Abuse Program at 831-242-4131.

Social Sharing