WHEN the Army's Criminal Investigation Command's special agents need to have evidence for a case analyzed, they send it to a cutting-edge laboratory located in Fort Gillem, Ga. The U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory isn't like the labs seen on television, but the facility is impressive.

Forensic evidence arrives at the lab's evidence-processing branch via a secure delivery system, Alonzo Rhodes, branch chief, explained. From the crime scene to the lab, all evidence is carefully handled, packaged and maintained to ensure its integrity throughout the process.

'This is where all evidence basically meets the lab, and is processed for distribution throughout the lab to the appropriate branches,' Rhodes said, while showing off the crime lab's evidence receiving area.

The packages, which are called containers, are stored in a vault, with the newest evidence at the front. When the technicians bring the containers out to process, they assign them tracking numbers before beginning the casework, he said.

'Most (containers) are double-packaged, with documents within the inside of the outer wrapping, while evidence is in the second wrapping,' Rhodes said. 'All we really do is open the outer packaging, take the paper-work out, review the paperwork,' and reseal the package before routing it to the appropriate evidence branch.

The evidence-processing branch is equipped to take something as large as a vehicle, and once even processed a chimney, Rhodes said. If evidence is too large to send, investigators can always contact them and request that an examiner come out to the scene.

Once the evidence is processed, it's sent to the appropriate branch. Sometimes the container must go to more than one branch.

'There's a priority of branches depending on what examinations need to be completed by those branches, say like trace,' Rhodes said. 'Trace' refers to trace evidence, a very small piece of evidence left at a crime scene that may be used to identify or link a suspect to a crime.

'Trace goes through first, because if everybody goes and opens that up it messes up the evidence within. It gives you cross contamination,' he added.

Chris Taylor, chief of the Trace Evidence Branch, said there are about six collection rooms used to process evidence, like clothing, for fibers, glass or paints. 'These are considered clean rooms. We want separation of subject and victim clothing at all times. If you have a third-party scene or you have multiple suspects, we'll use a variety of rooms,' he said.

Trace evidence works with the smallest samples imaginable. Taylor displayed a picture of an enlargement of a penny, with fibers, paint and glass chips next to it-the penny appeared enormous by comparison.

'These size samples right here would be plenty big enough for us to do all the analysis we need to do to say, if these items are consistent with, say, a known paint sample from a vehicle,' Taylor said.

'Every contact leaves a trace,' he said. The branch can analyze fibers, chemical or crystalline materials, powder, soil, fire debris, gun residue, explosives-even glitter-and trace it back to potential suspects.

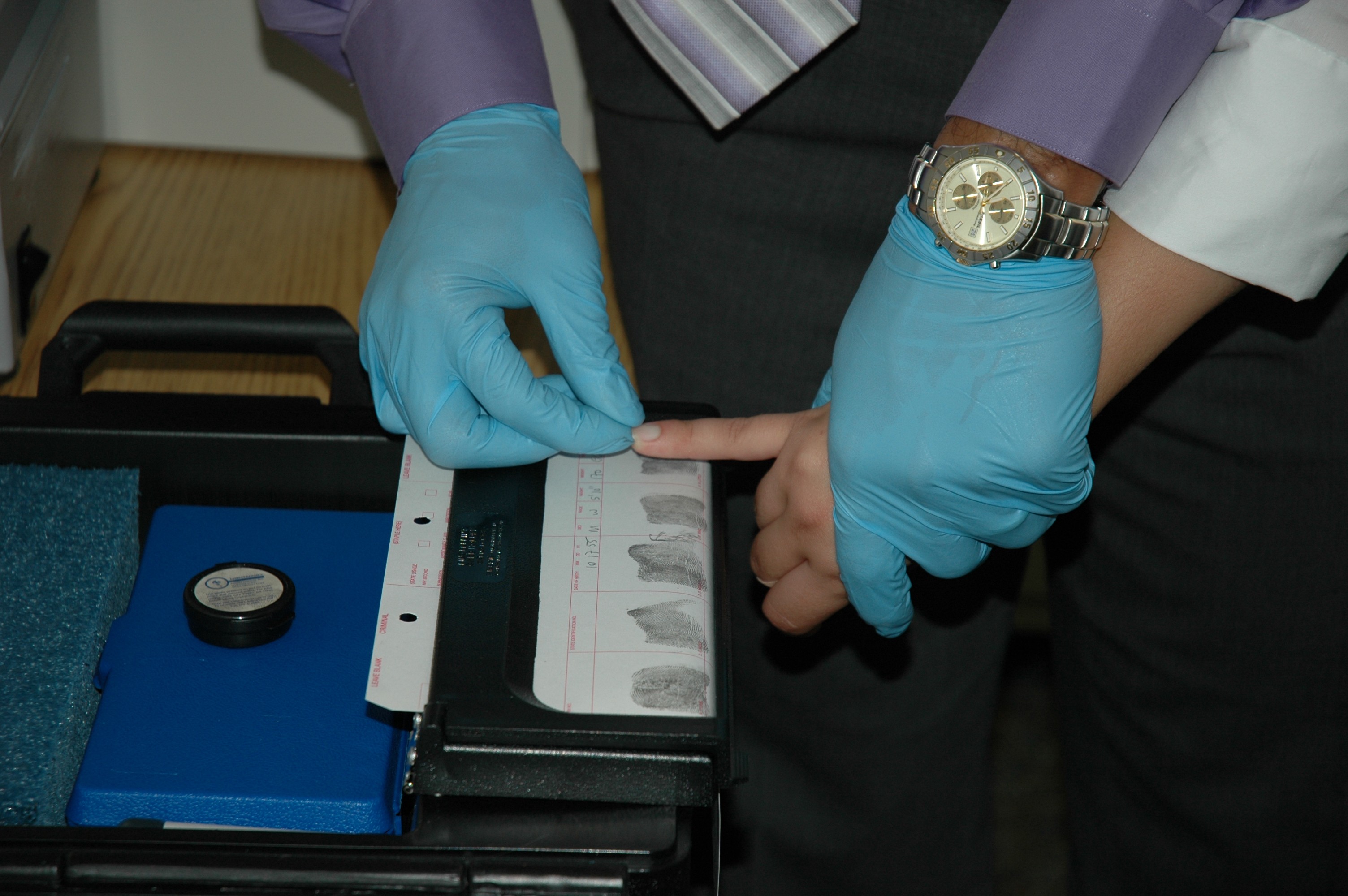

In addition to pulling fibers or traces of soil from evidence and using them to determine a suspect, examiners can also pull fingerprints from almost any surface.

The Latent Print Branch is responsible for analyzing fingerprints and other impressions made in the ground, or other substances.

'Probably one of the better, the most overlooked piece of forensic evidence that there is, is footwear,' Don Coffey, the Latent Print Branch chief, explained. 'Because you don't hover into a scene, unless you rappel down there, you're going to walk in and walk out. So if you have the ability and the equipment to capture those footwear impressions, they are always there, whether it's carpet, on dirt, dust, tile or whatever.'

Tire-track impressions also make up a good portion of the work done in latent prints. Investigators will take castings of the track, and latent print examiners will try to find a match in a tread database.

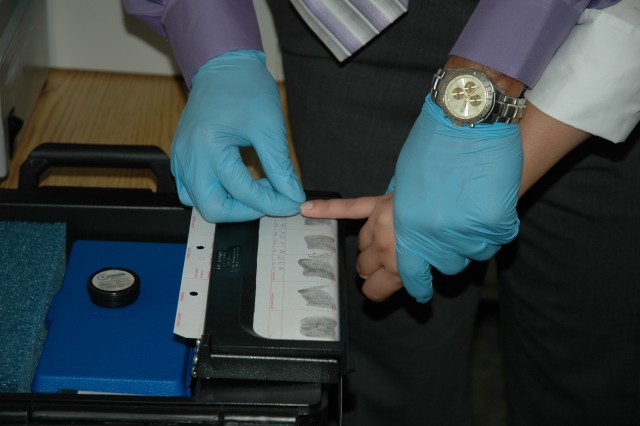

But of course, fingerprint analysis is the bread and butter of the branch.

The first thing to attack in a fingerprint is moisture, Coffey said. Fingerprint powder adheres to the moisture, and enables an investigator to lift the print from a surface, which is the 'classic' method.

In the early 1980s, examiners discovered 'super-glue fuming', or cyanoacrylate fuming. According to CID officials, a CID special agent was instrumental in helping to develop and bring this technology to U.S. law enforcement.

'Cyanoarcrylate, when heated, turns into...a gaseous form. And the gaseous form will attach itself to the molecules of moisture, and then it plasticizes (or makes plastic), that moisture,' Coffey said. The cyanoacrylate print is very durable. 'You can wipe this and rub on this and it's not going to come off. If it were a print, it would be gone.'

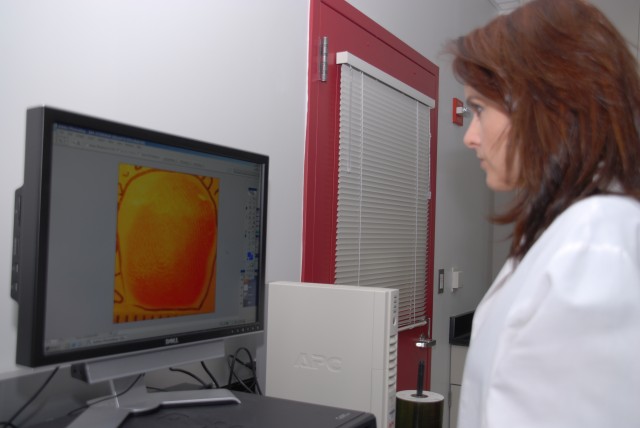

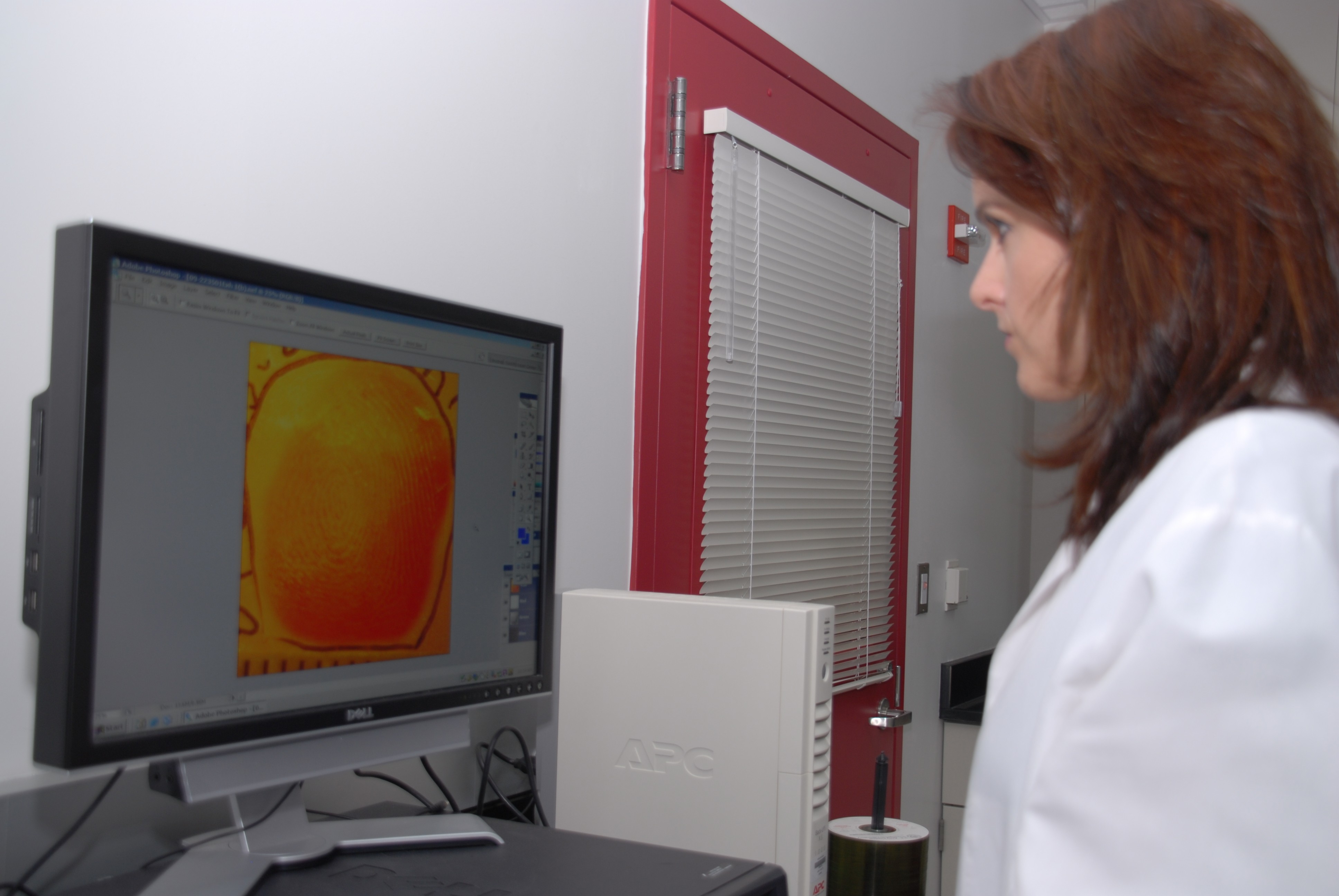

Other techniques used to lift fingerprints include chemical development with ninhydrine, which will make the prints show up blue when heated; and spectral photography, which uses the whole light spectrum to take pictures of otherwise invisible fingerprints.

'You can develop a print in paper that's like 200 years old,' Coffey said.

In fact, examiners recently lifted the prints of the nation's founding fathers off supporting documents related to the Declaration of Independence. 'So, (you can lift prints from) just about anything you can talk about with the exception of water in a liquid state, fire and air.

'I've seen fingerprints come up on ice cubes before,' Coffey added.

In a separate interview, Jeff Salyards, director of the Science and Technology Division, described how fingerprint technology is evolving. A naval laboratory in California is in the process of developing what Salyards terms a 'magic fingerprint powder.'

'They think they might be able to develop a nanoparticle that sticks to fingerprint residue and nothing else. So you could look at (a) table, throw some on, blow it off, and the only thing that would be there are fingerprints,' he said.

Innovative technology is not limited to the Latent Print Branch, either. The Firearms and Toolmarks Branch at USACIL uses a state-of-the-art wet trap for ammunition recovery, as well as a 20-foot-long cotton trap, used to capture .50-caliber bullets.

'Now we can, for the first time ever, capture .50-caliber machine gun bullets right here at the Army Crime Lab,' Don Mikko, chief of firearms and toolmarks, said.

The branch conducts microscopic comparisons of firearms, ammunition and other tools. They also restore serial numbers and reconstruct shootings, Mikko said.

'What's unique about our branch in (relation to) toolmarks, is that we're the only crime laboratory-firearms branch, that is-that (handles) a large magnitude of toolmark-related cases,' he said.

In the recovery rooms, examiners will test-fire guns into the water tank, wet trap, or cotton box, and recover the bullet and cartridge, and then make a comparison against the evidence. 'We can tell you if a bullet or cartridge case was fired in and through that gun, to the exclusion of every other gun in the world,' Mikko said.

'Every single firearm or every single tool has its own fingerprints, but we don't call them fingerprints-we call them individual characteristics,' he added.

Once evidence has made it through all the appropriate branches, it goes back to evidence processing. There, it's repackaged with the results and returned to the submitter, Rhodes explained.

The Forensic Analysis Division receives roughly 3,000 cases a year from all military law enforcement agencies, each filtered first through evidence processing, and then the other branches. The casework is detailed, and can be time consuming, but the results are important pieces in an investigative puzzle.

'It's amazing to me how hard our agents have to work, the pressure they're under, the stakes they're under to get this kind of stuff right,' Salyards said. 'That's just an amazing resource that the Army has in the agent corps.'

Social Sharing