CRIME happens everywhere: on-post and off, in garrison and even in a combat zone, so Army Criminal Investigation Command agents must be prepared to solve cases anytime, anywhere.

Criminal investigations on the battlefield are 'exponentially' different than those in garrison, said Special Agent Ronald Meyer, former chief of the Forensics Training Branch at the U.S. Military Police School. They present their own challenges, including the heat, the often limited time to process a crime scene and the ever-present risk of attack, not to mention the potential of finding gruesome war-crime evidence like the mass graves Meyer processed in Iraq in 2003.

'The threat is different,' he said. 'We were processing mass graves. I'm not worried about being at a location for an extended period of time and exposing myself to the enemy...here at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. Crime scenes have a tendency to be more hasty, higher threat, in Iraq and Afghanistan...so it's a lot different.'

Regular Soldiers, however, fascinated by forensics they watch on television crime shows, have become force-multipliers for agents. In the past, a unit would probably have cleared a building and moved on or detonated an improvised explosive device, but now they might dust for fingerprints, take water bottles for DNA testing, and collect other evidence first.

Meyer actually sends a mobile training team to places like the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, Calif., to teach deploying Soldiers about site exploitation and battlefield forensics. In addition, CID provides battlefield forensic kits to brigade combat teams that include fingerprint powders, brushes, cards and rubber gloves.

According to Jeff Salyards, the director of science and technology (the Army's term for research and development) at the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory at Fort Gillem, Ga., a new, rugged, GPS-enabled camera/computer/printer for Soldiers is also in the works for labeling and recording evidence.

'We're calling (it) a site-exploitation device,' he said. 'Right now...downrange, I'm in battle rattle, I've got gloves on, a helmet on. I've got a digital camera, hopefully. I've got a notepad.... It would be great if we could give them a digital camera that's GPS-enabled, that maybe has a way to input some information, and maybe even has a small printer attached that could give you a barcode. So this camera knows who I am, knows why I'm there...knows where I am. I take a picture of this thing. I may have a screen or something where I can type in a little information, one line, about what this is. And then I hit print and there's now a bar code. I don't need a bunch of notes.

'Part two was we teamed with the biometric community. The guys in the field already have to carry a tactical biometric collection device.... So we're teaming with those folks to say wouldn't it be great, instead of going, 'Here's your site exploitation device, here's your biometric thing,' if we just go, 'Here's one device that can be used for all those things''

'And we're also working with the cyber piece so there's a computer that hides on that device...that lets you...look for certain files.... There's a USB device on here, so if I plug it into a computer, let me...see if there are any bad files. I'm excited...anything that makes those guys (have) to carry less stuff.... That seems to be a common cry.... You're carrying this anyway. We're just going to make it more capable for you,' Salyards continued.

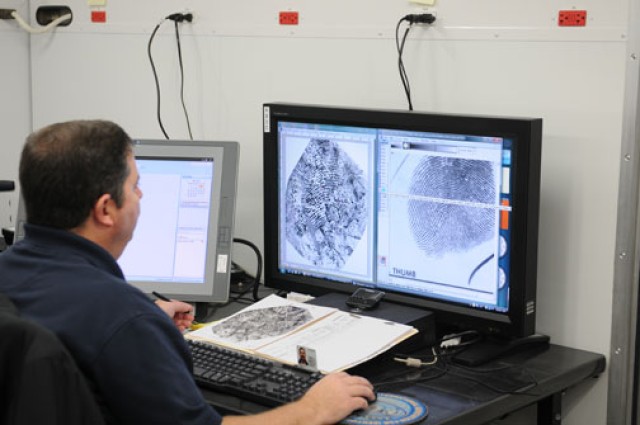

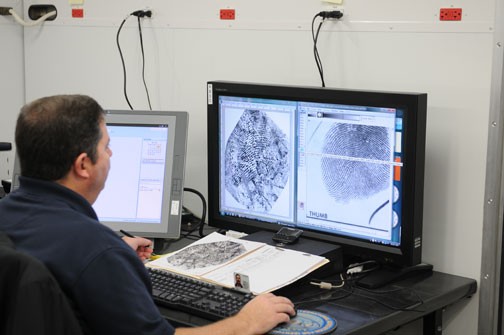

Until recently, investigators also had to ship all of their evidence back to the States for processing at USACIL. But in 2005, the first joint expeditionary forensics facilities were established in Iraq to process fingerprints, firearms and even DNA collected downrange. The JEFFs have since been deployed to Afghanistan as well, with additional labs ready to deploy on an as-needed basis.

Some of the labs are still in development, and many of the 150-odd technicians have yet to be hired, but the ultimate goal is for the teams to rotate and spend two months stateside for every month of deployment, according to Col. Martin Rowe, chief of the Expeditionary Forensics Division.

'The challenge came, you know, we have all the technology and all the procedures well established here,' he said. 'How do you take that and apply it to an area where you don't have power all the time, or you don't have clean water or you've got dust and sand' Ruggedizing the equipment to make it operate in that type of environment was a huge challenge.'

Evidence processed at the JEFFs has been used to link senior Taliban leaders to crimes, update watch lists, increase force protection and prosecute criminals in Iraqi courts.

'As far as I know, everybody's really pleased with the first rotation and support we're providing,' said JEFF Operations Specialist Jerzy Mikulski, a retired CID special agent who recently returned from Afghanistan. 'The time it takes to return any kind of forensic data back to the United States, can mean Soldiers' lives being saved. If we process evidence and it leads to some kind of active investigation, or provides some intelligence or data to units fighting, it's obviously very beneficial. Having assets on site or in theater provides (a) far more timely exchange of information.

'We take weapons, we process them for DNA, process them for fingerprints. We submit them to firearms and tool marks. Perhaps this weapon was fired before on our Soldiers and we recovered a round, and we compare them and we can tie it directly to a group of people or maybe even an individual who was involved in a sniper attack,' he explained.

The JEFFs, Rowe added, could also be very beneficial in a natural disaster like Hurricane Katrina or the recent earthquake in Haiti, because the JEFFs will eventually be able to deploy on a moment's notice.

'That's another one of the things that we're planning.... When Hurricane Katrina came through, it wiped out three or four crime labs-the state lab, county lab and the city lab so they were without. The National Institute of Justice went down there and set up some mobile labs, but we could certainly see this...maybe not doing forensic criminal work, but doing identification of remains...pulling...and profiling the DNA samples,' he said.

Meyer added that from identifying remains in mass graves or after natural disasters, to keeping insurgents off forward operating bases, the possibilities are limitless and will change the future of battlefield forensics.

Soldiers will take 'basic law enforcement skill sets and (apply) them to the battlefield for targeting, sourcing, prosecution, force protection and (medicine), which are the five forensic functions.... The future is that the military police will be the primary collectors of evidence on a battlefield...the lab will ultimately analyze it, and...if it's noncriminal, that analysis will then be given to the senior tactical commanders for operational decisions,' Meyers explained.

Social Sharing