HUNTER ARMY AIRFIELD, Ga. - The 1920s marked the true beginning of civilian aviation in the United States. By 1930, nearly 1,700 civilian airports were established in the nation. In 1927, the City of Savannah bought 900 acres of woods, pasture, and swamp three miles south of the city limits for the first Savannah Airport - later known as Hunter Field.

In three years, using mostly chain-gang labor, Chatham County ditched the area, graded the field with 400,000 cubic yards of sand, and planted it with Bermuda grass. The landing area was 4,500 feet long and 3,500 feet wide. Aircraft could take off and land in any direction. The original airfield lay roughly on what is now Hunter Army Airfield's parking apron.

On May 19, 1940, the city officially dedicated the airport as "Hunter Field," the same year the U.S. began re-arming in preparation for war. The government increased funding for new equipment and bases and instituted a peace-time draft. The Air Corps needed new airbases to accommodate its growth, and in August 1940, selected Hunter Field as a light bomber training base.

Within two months, the Air Corps transferred 3,000 personnel of the 3rd and 27th Bomb Groups, and a hundred A-18 trainers, A-20 light bombers, and B-18 medium bombers to the new base, sharing the airfield with the civilian airport.

The 3rd and 27th Bomb Groups trained at Hunter Field throughout 1940-41, participating in large-scale Army maneuvers in the Carolinas. On Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. All passes from Hunter Field were immediately cancelled and airmen were required to wear uniforms at all times as the U.S. faced war with Japan and Germany.

From 1941 to 1943, the base grew to a population of 10,000, expanded its boundaries from 900 to nearly 3,000 acres. It expanded runway capacity, built aircraft parking aprons, and trained ground support squadrons, bomber groups and fighter groups.

After 1945, Hunter Field reverted to the Savannah Municipal Airport. The airport only used a small fraction of Hunter Field's cantonment, the balance leased by the Federal Public Housing Administration to various public and private enterprises.

As the 1940s ended, the Soviet Union, formerly a World War II ally, showed itself to be an implacable foe of western capitalism and democracy. In 1947, President Truman signed the National Security Act, reorganizing the U.S. defense and intelligence establishments and making the Air Force completely independent and most important branch of service because of its role in atomic bomb deployment.

In 1948, there were less than 60 atomic bombs in the U.S. nuclear arsenal, stored in four "Q Areas" controlled by the civilian Atomic Energy Commission. By 1950, SAC consisted of 14 bomb wings, flying mostly B-29 and B-50 propeller medium bombers, or huge B-36 piston-pull heavy bombers. As part of SAC's southern strategy, in 1949, SAC stationed the 2nd Bomb Wing and its B-50 bombers at Chatham Field, a World War II airbase built a few miles west of Savannah.

However, Chatham Field had inadequate barracks and operations facilities, and proved unsatisfactory. In order to keep SAC in the Savannah area, the city offered to exchange Hunter Field for Chatham Field.

In September 1950, the switch occurred. Hunter Field became Hunter Air Force Base, while Chatham Field became the Savannah Municipal Airport, now known as the Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport.

When SAC arrived at Hunter AFB in 1950, they found a neglected World War II-era airport. Buildings creaked with rotten siding and broken windows, while asphalt roads showed ruts and holes, and grass grew through the pavement of aircraft parking aprons. A land conflict in Asia soon accelerated the pace of base construction and development.

By January 1951, SAC had slated a second bomb wing for Hunter AFB, and in 1950-51 spent over $5.6 million on the base, mostly in repairing World War II buildings, roads and runways, and expanding the base to its current boundaries west to the Little Ogeechee River and east to White Bluff Road. Hunter AFB received $24.5 million from Congress and spent $2.5 million on building the installation's runway.

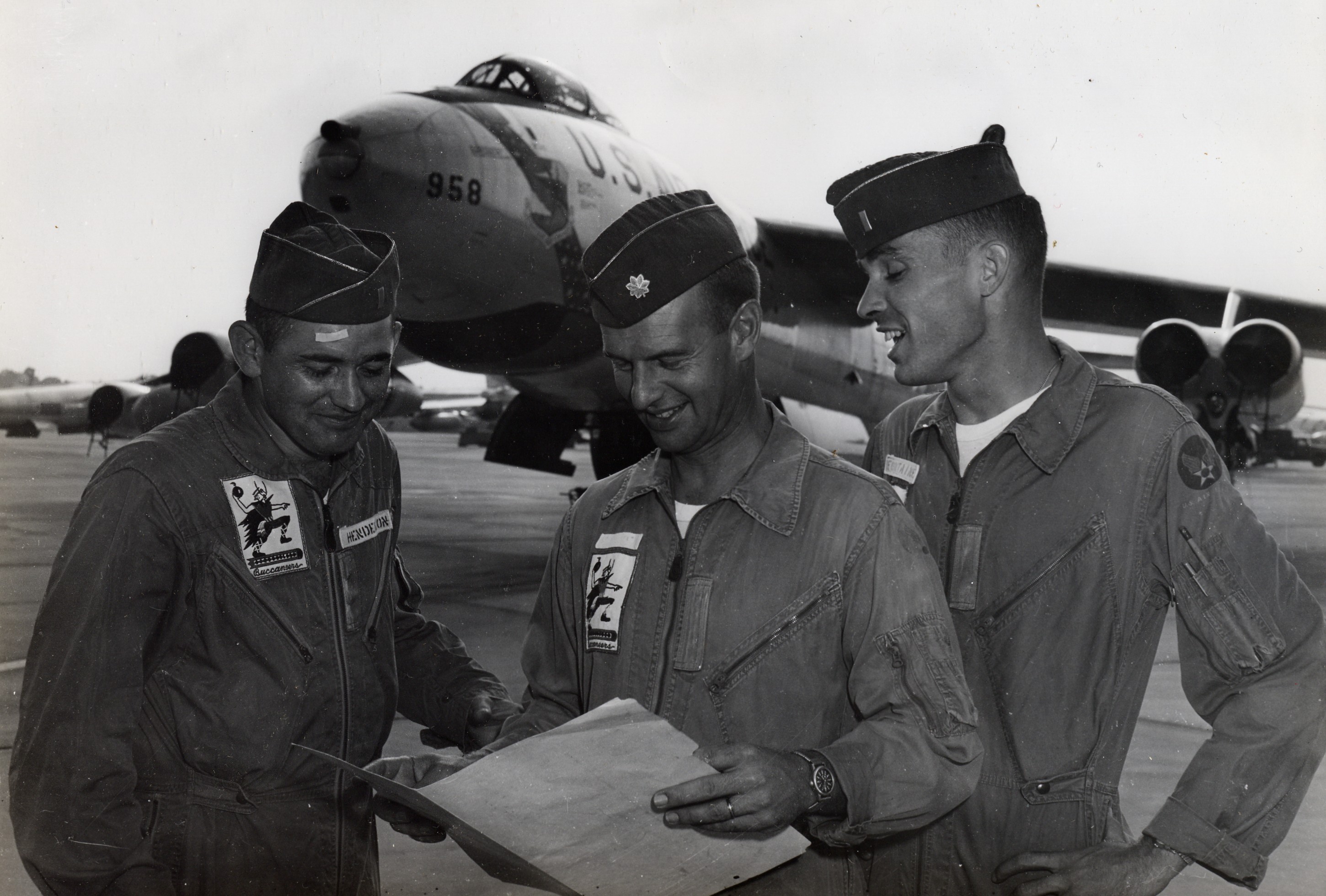

In the mid-1950s, SAC began basing bomb wings in the northern tier of the country, closer to the Soviet Union when flying over the Arctic Circle, and away from heavily populated areas. In 1955, the first B-52 heavy bombers-with greater range and payload capacity than the B-47-came online, while the U.S. deployed ICBMs by 1959. The development of ICBMs and the B-52 precluded the need for B-47 bases in the southeast. Hunter AFB became obsolete.

By 1960 SAC had transferred the 30th from Hunter AFB and announced the base's eminent transfer to Material Air Transport Service, another Air Force command.

In October 1962, six months before SAC was scheduled to leave Hunter AFB, the Soviets began installing medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba. The U.S. imposed a naval blockade on missile shipments and demanded the missiles' removal.

Hunter AFB's 2nd Bomb Wing already had 17 B-47s on Reflex alert overseas, and dispersed 13 other bombers to Shaw and Charleston AFBs in South Carolina, all in full Emergency War Order configuration, loaded with nuclear weapons and Jet-Assisted Take Off rockets for lift-off.

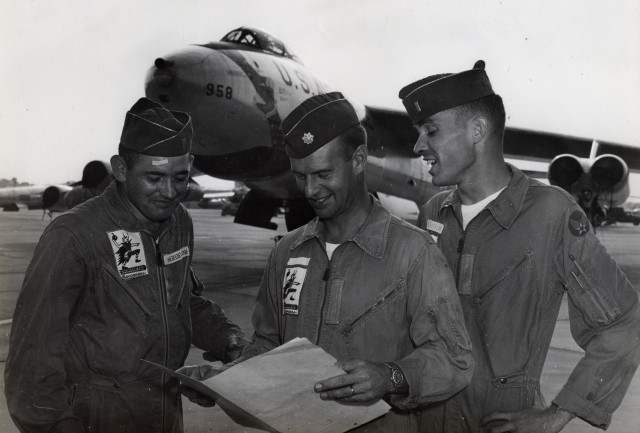

Beginning Oct. 20, 1962, the installation hosted the B-47s of the entire 306th bomb Wing. On Oct. 22, SAC placed its fleet at DEFCON 3, increasing readiness and alert levels above normal levels. By Oct. 24, all aircraft at Hunter AFB, 60 B-47 bombers with full nuclear payloads, sat silent on the aircraft parking apron and the "Christmas Tree" apron at the alert area, waiting for the balloon to drop. Other SAC bases in the U.S. and overseas were on full alert.

Overhead, B-52s flew on airborne alert. The Soviets stepped back from the abyss on Oct. 29, 1962, pulling the missiles from Cuba while President John F. Kennedy secretly agreed to withdraw U.S. missiles from Turkey.

Within six months of the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis, all SAC aircraft had left Hunter AFB. In April 1963, SAC transferred Hunter AFB to the 63rd Troop Carrier Wing of MATS, which stationed 60 C-124 cargo planes and 4,300 men to the installation.

In 1964, the Department of Defense announced Hunter AFB's closing. Built as a SAC base, Hunter AFB did not have the facilities needed to support transport missions.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Army developed troop-carrying transport helicopters, helicopter gunships designed for close air support, and tactical doctrine for airmobile warfare.

These efforts paid off in a tactical sense when the U.S became involved in the Vietnam War. In 1965, U.S. combat troops were sent to bolster a shaky authoritarian regime in South Vietnam against an insurgency sponsored by Communist North Vietnam. The helicopter became the crux of the Army's tactical efforts, essential in jungle terrain for air transport, fire support, medical evacuation, and supply.

The need for more helicopter pilots drove the expansion of the Army's aviation program, which saved Hunter AFB as a military base. In December 1966, DoD announced that the official new home of the Army's Advanced Flight Training Center would be Hunter Army Airfield and Fort Stewart. The airfield's massive parking apron, built by SAC for jet bombers, offered more than enough space for helicopter training operations.

Hunter became one of the Army's key helicopter training sites during the Vietnam War. Between 1967 and 1972, Hunter and Fort Stewart trained 11,000 rotary wing pilots and 4,328 fixed wing pilots, including 1400 South Vietnamese aviators. The U.S. withdrew all combat troops from Vietnam in the early 1970s, and in 1972 the Army closed Hunter.

The Army reopened Hunter in 1974 and designated it a sub-post of Fort Stewart and a base for the 24th Infantry Division's helicopter and support elements, including the 1st Ranger Battalion. By the late 1970s, Hunter had become the U.S. Army's premier rapid deployment node on the eastern seaboard, thanks in no small part to facilities left behind by the Air Force, including the runway, parking apron, and the old SAC alert area, now called "Saber Hall."

Special Forces troops and elements of the 24th Division could deploy as rapidly as possible to nearly anywhere in the world, making it a potent offensive resource in the Cold War.

In 1990-1991 the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized) participated in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, taking part in the liberation of Kuwait and the destruction of much of Saddam Hussein's Iraqi Army. Few missions in the 1990s had the clarity of Desert Storm, and the Army conducted multiple open-ended peace-keeping and humanitarian missions in countries as diverse as Haiti, Somalia, and the former Yugoslavia. In 1996, the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized) was re-flagged the Third Infantry Division, "The Rock of the Marne."

Hunter remains an important deployment and support base for the Army and other joint services, thanks to its existing airfield facilities and location adjacent to Fort Stewart and the east coast ports of Savannah and Charleston. In January 2003, Soldiers in the 3rd ID (Mechanized) were the first U.S. unit to enter Baghdad for Operation Iraqi Freedom during the invasion. The entire division deployed from Hunter to Kuwait in the weeks that followed. The 3rd ID spearheaded Coalition forces, fighting its way to Baghdad in early April, leading the end of Saddam Hussein regime.

After combat, 3rd ID Soldiers shifted focus to support and stabilization operations and rebuild the war-ravaged country. The division returned in August 2003.

The division is currently on its fourth deployment.

The majority of Soldiers from the 3rd Combat Aviation Brigade, from Hunter began arriving in Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in late summer, 2009.

The 3rd CAB is organized by four multifunctional task forces comprised of UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters and MEDEVAC helicopters, AH-64D Apache Longbow attack helicopters, CH-47D Chinook helicopters, and the OH-58 Kiowa Warriors. The brigade's previous deployments were during the initial invasion into Iraq in 2003, OIF III in 2005 and OIF V in 2007.

It's been 60 years since the Air Corps developed Hunter into a military airfield.

It served first as a bomber and air transport base for the Air Force, then as an Army helicopter training base, and finally as a rapid deployment node and home for an infantry division's aviation units and tenants, including U.S. Special Operations, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, U.S. Coast Guard's Air Station Savannah, Georgia Air and Army National Guard, 224th Military Intelligence Battalion, 260th Quartermaster Battalion, Tuttle Army Health Clinic and the U.S. Intelligence and Security Command.

(Most of the above historical information was compiled from material provided by the Environmental Division, Directorate of Public Works, Fort Stewart, Ga.)

Social Sharing