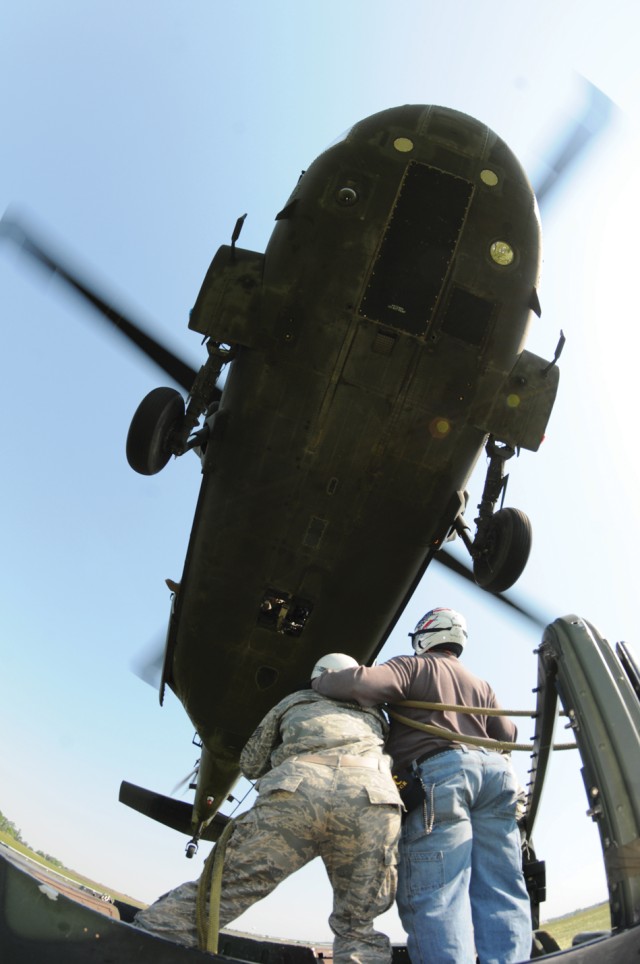

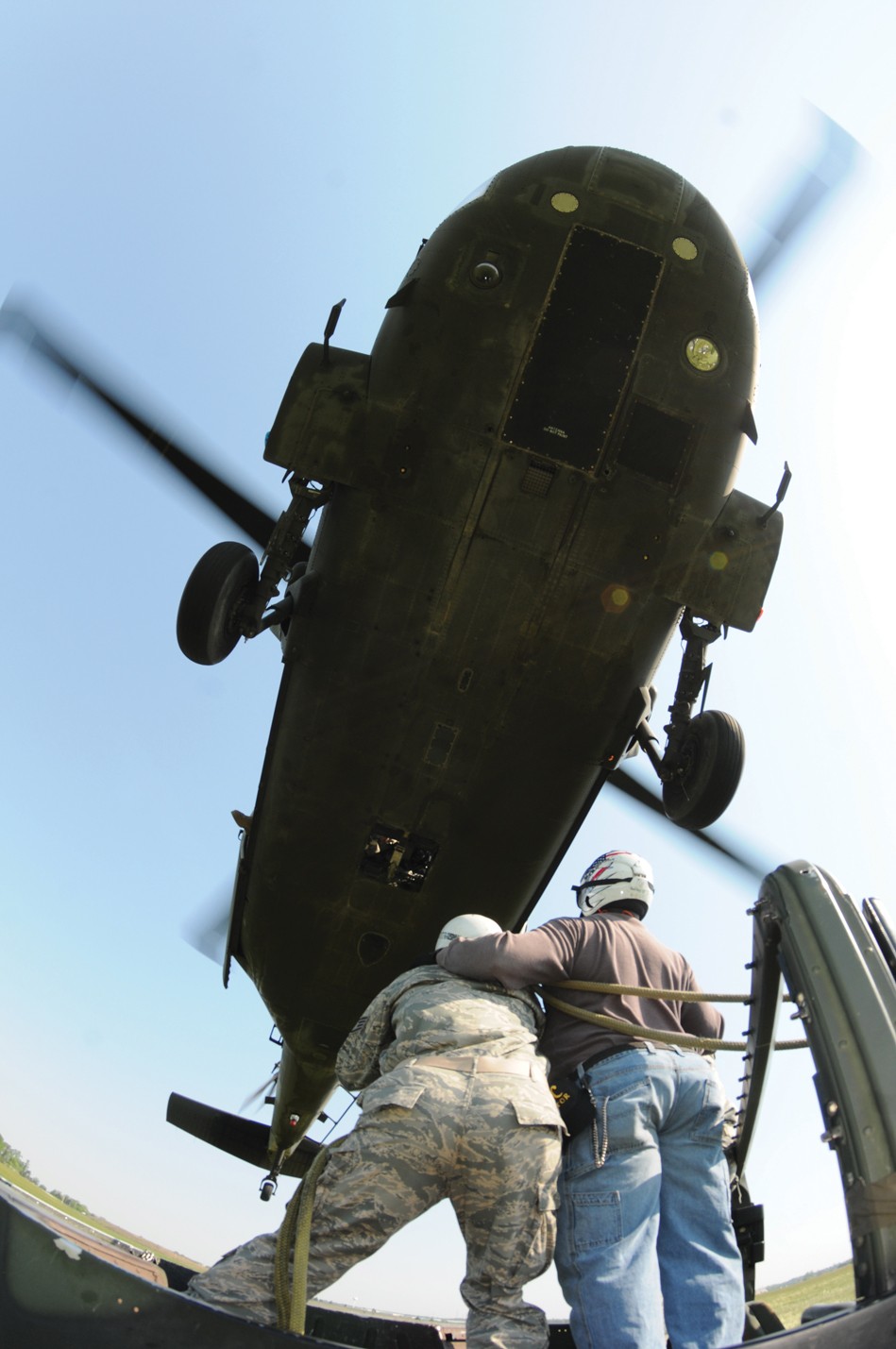

FORT LEE, Va. (April 29, 2010) -- Picture this: Four tons of wavering, hulking machinery hovering just inches above your head; 50 mph winds being thrust toward you in continual streams; and giant, menacing propellers producing deafening thuds that slice right through you.

It's an image most of us can't fathom.

But it's a reality that military members and Civilians enrolled in the sling load course must confront. Twenty-two Soldiers, Airmen and Marines came face-to-face with that expectation during the final day of the Sling Load Inspector Certification Course that ended April 16 at McLaney Drop Zone here.

The SLICC teaches military members and civilians how to properly inspect and prepare cargo loads for helicopter transport.

"This is a very difficult course, but it's going to provide these Soldiers, Airmen and Marines with the skill set to be great assets to their commanders," said Sgt. 1st Class William Baker, sling load noncommissioned officer in charge.

Baker is a rigger assigned to the Aerial Delivery and Field Services Department, the element of the Quartermaster School responsible for the training. He said the 40-hour SLICC teaches students, among other things, procedures required to stand underneath a hovering aircraft and execute hookups to such cargo as a HUMVEE tactical vehicle.

Baker provided a simplistic explanation of the procedure:

"One student (stands) on top of the HUMVEE and provides the static probe, which discharges the electricity from the aircraft into the ground. This is necessary because aircraft generate static electricity as the propellers turn," he said. "The other student provides the actual hookup."

A supervisor, added Baker, stands between the students to ensure all safety measures are taken.

Simplicity aside, several factors are important to a successful hookup, said Staff Sgt. Willie Johnson, an ADFSD instructor and rigger:

The pilot has to hover the aircraft, keeping it as still as possible to facilitate the task at hand.

The student holding the probe must keep it in contact with the aircraft hooks while his classmate performs the hookup.

Lastly, the student attaching the hook to the aircraft must stand firm in the face of the rotor wash (propeller-driven wind gusts), ensuring he or she doesn't assume a crouched or stooped position. That could cue the pilot to move the aircraft lower, increasing the task's difficulty.

Spc. Byron Adams, a Utah National Guardsman participating in April 16's exercise, said all of this drove him to varying levels of anxiety just before his turn at the hookup.

"It was kind of nerve-racking," said Adams. "I just wanted to do it."

When he got his turn at doing "it," Adams and his classmate followed the procedures and executed a successful hookup, leaving him with a sense of relief and elation.

"The main thing I worried about was not getting shocked," he said afterward, "but it was a rush, man; it was pretty cool. I actually liked it a lot. When the rotor wash hits you, it was kind of a cool feeling. It lets you know that it can be potentially dangerous, but it's pretty fun at the same time too."

Soldiers brave the potential dangers of sling load operations to provide critical logistical support to U.S. and Coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is especially critical in Afghanistan, where rugged terrain and poor roads make timely transport of supplies and equipment difficult.

"With the mountainous terrain in Afghanistan, you can't necessarily drive everywhere you need to go," said Baker, "that's why sling load is so important right now. That's our prime mover of equipment (and supplies) in theater."

Sling load will likely continue to play an important role in the sustainment of forces in Afghanistan, especially as U.S. forces increase there. The QMS will continue to support the effort. It graduated more than 2,200 students last year and is expected to graduate more than 2,300 by the end of this year.

Social Sharing