MADIGAN ARMY MEDICAL CENTER, Tacoma, Wash. -- In December 2000, columnist Bob Welch stumbled upon the frozen trail of a 60-year-old story about the first Army Nurse Corps casualty to die after the D-Day invasion.

The true account of Second Lt. Frances Slanger became the subject of his book, American Nightingale: The Story of Frances Slanger, Forgotten Heroine of Normandy, and the trail started with a letter that Slanger had written to Stars and Stripes in the very early hours of Oct 21, 1944.

"The rain is beating down...with a torrential force. The fire is burning low and just a few live coals are on the bottom," Slanger wrote. "Couldn't help thinking how similar to a human being the fire is. If it is allowed to run down too low, and if there is a spark of life left in it, it can be nursed back. So can a human being. It is slow; it is gradual; it is done all the time in these field hospitals."

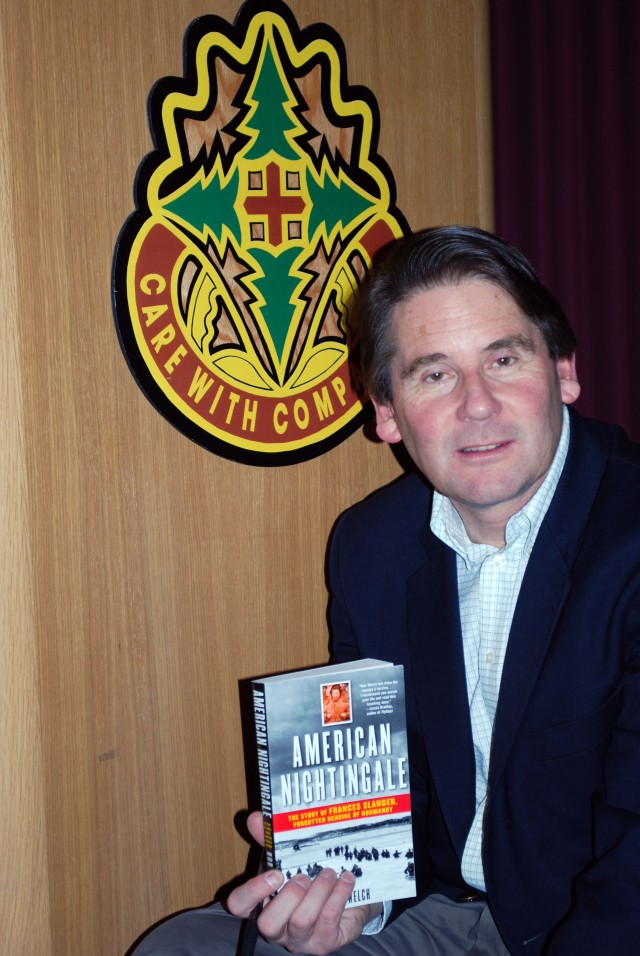

Welch spoke recently at Madigan Army Medical Center to celebrate the 109th Army Nurse Corps anniversary. His book describes Slanger's persistence in becoming a nurse, which was not a widely accepted profession for a Jewish woman in the 1930s. She was declined admission to the Boston City Hospital School of Nursing, and had to reapply before finally being accepted.

After graduation and in the midst of a World War, Slanger joined the Army Nurse Corps, but was denied an overseas assignment because of her bad eyesight. Somehow, though, she talked her way into a European tour, and deployed with the 45th Field Hospital.

Slanger's arrival came four days after the invasion of Normandy as she jumped out of a landing craft onto a beach in France with 17 other Army nurses. They were greeted by truckloads of wounded Soldiers.

"When people hear about World War II nurses, they seem to think about nurses wearing white dresses and white caps strolling across some well-shined floor in a big, beautiful French hospital," Welch said. "These nurses were wearing three-pound helmets and Army fatigues and there were bodies rolling up in the surf."

It was four months into her deployment and after the field hospital had moved to Belgium that Slanger wrote her letter. According to Welch, Slanger's letter seemed to be provoked by letters that Soldiers had written to the newspaper, praising the work of the nurses. She wanted to make sure the Soldiers were honored in writing, too.

"We wade ankle-deep in mud, but you have to lie in it. Sure we rough it, but in comparison to the way you men are taking it, we can't complain," Slanger wrote. "After taking care of some of your buddies, seeing them when they are brought in bloody, dirty with the earth, mud and grime, and most of them so tired. Seeing them gradually brought back to life, to consciousness, and to see their lips separate into a grin when they first welcome you. Usually they kid, hurt as they are. It doesn't amaze us to hear one them say, 'Hi ya babe.' We have learned a great deal about our American Soldier, and the stuff he is made of."

The next morning, Slanger mailed her letter, but she didn't live to see her words in print. That evening, the Germans shelled the field hospital, which, according to Welch, had never been done before that night in the European theater, and hasn't been done since that night. Three people were killed, including Slanger.

The editor of Stars and Stripes printed the letter as a guest editorial, not knowing Slanger was dead, and Soldiers began writing thank you letters to her.

"These Soldiers had been fighting every day since they landed. They had lost their sense of humanity, lost most of their sense of dignity, and lost their sense of hope," Welch said. "Suddenly, along came this nurse who wrote this letter...and it absolutely melted their hearts and renewed their sense of hope."

When the newspaper reported a week later that Slanger had been killed, Soldiers then began writing letters demanding that Slanger's memory be kept alive somehow. Very soon afterwards, she was awarded the Purple Heart posthumously and a hospital ship was commissioned in her name.

In Welch's book, he reprints a portion of a letter written by an Army Air Force air gunner to Stars and Stripes describing the impact Slanger had as a nurse: "Frances Slanger is a great woman. We say it because her memory in our minds will linger steadfastly long after the final gun is fired in this war. Why' Because Frances Slanger pointed out the only genuine rule for peace on earth: human love and understanding."

Social Sharing