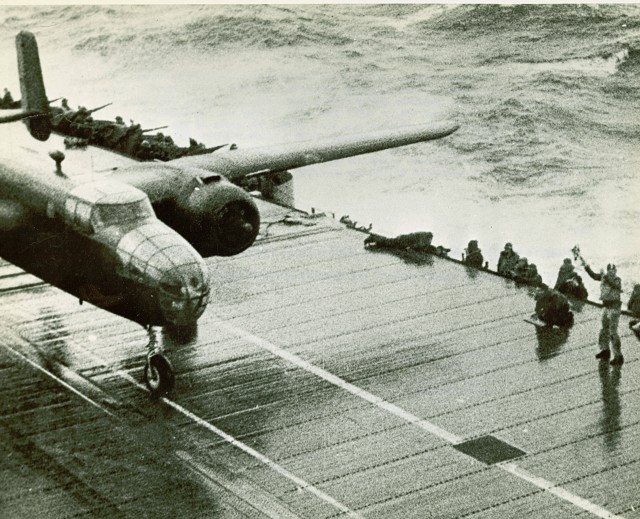

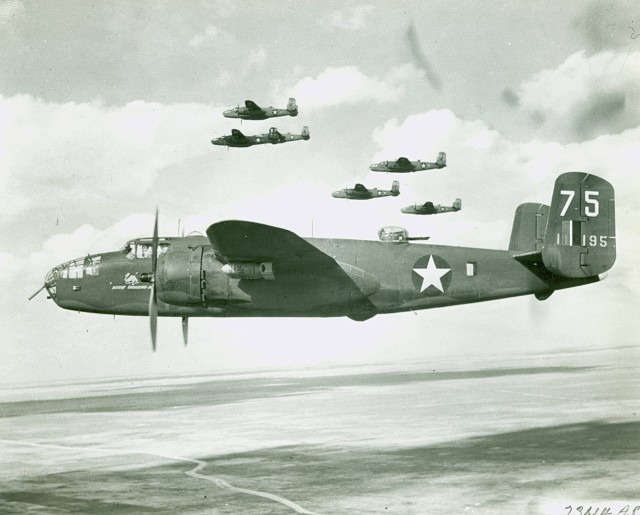

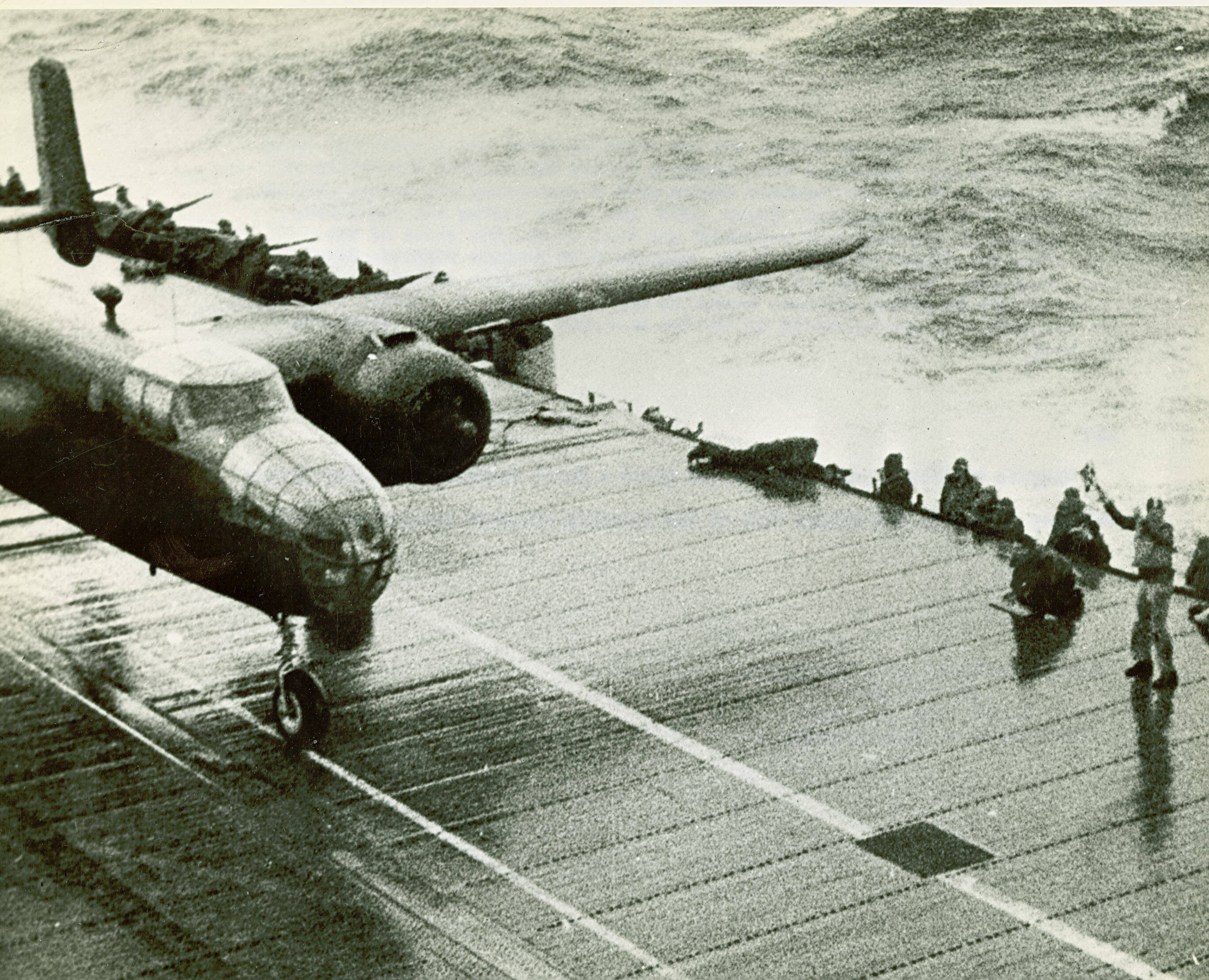

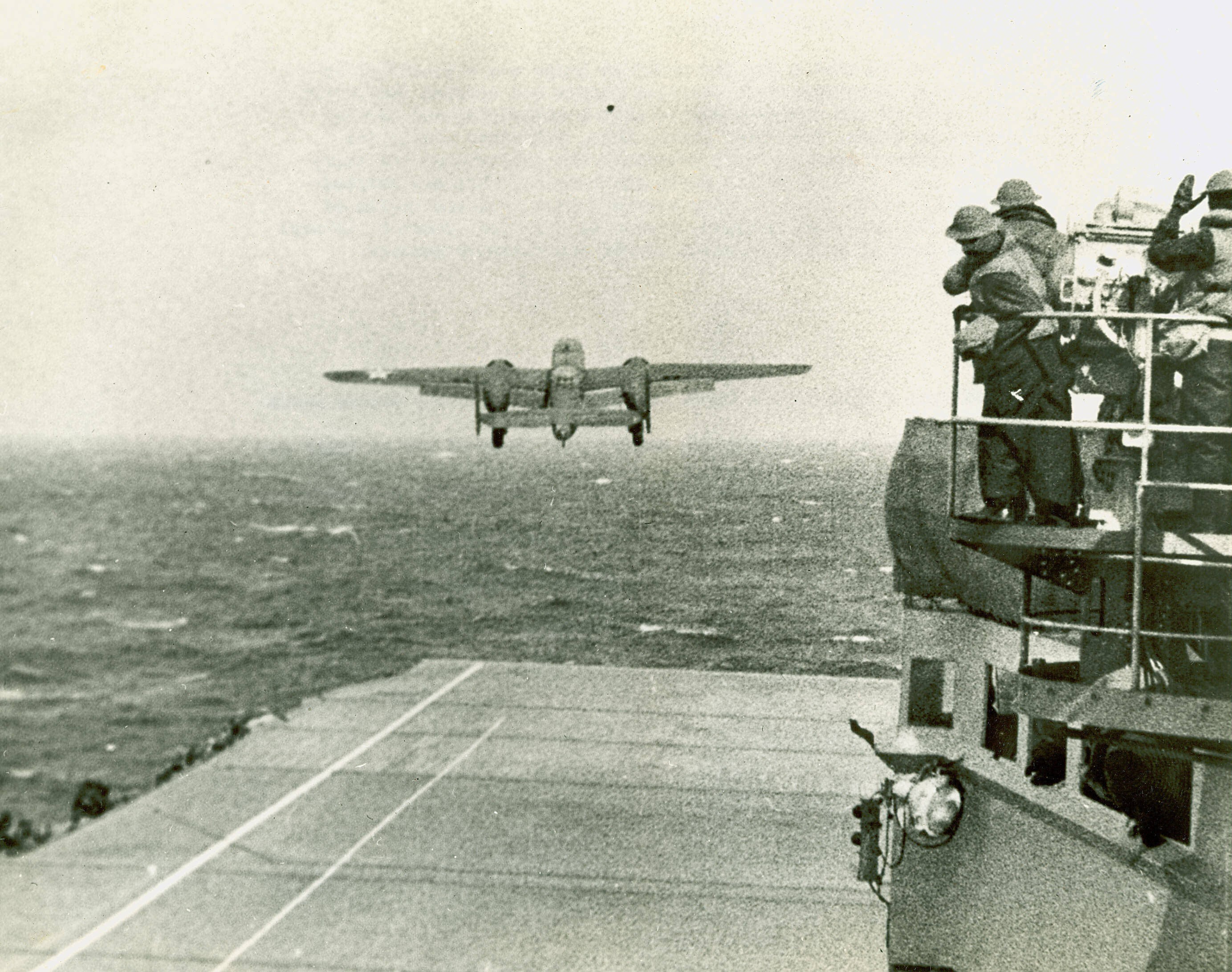

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, led to a declaration of war and President Franklin RooseveltAca,!a,,cs insistence on a retaliatory attack on the Japanese homeland. With much of the Pacific Fleet sunk or severely damaged, offensive options were greatly limited. An enterprising Navy officer, Captain Francis Lowe, envisioned a plan that made the best of the military assets at hand. Fortunately, the NavyAca,!a,,cs carriers had been at sea and escaped destruction at Pearl Harbor; however, the Navy had no long-range bombers. The Army had the bombers but no bases from which to launch the attack. LoweAca,!a,,cs concept was to use aircraft carriers to transport land based bombers to within striking distance. Army Air Forces commander General Henry H. Aca,!A"HapAca,!A? Arnold and U.S. Fleet commander Admiral Ernest J. King supported the plan, and training began. General Arnold selected Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle to organize and lead the mission. With no carrier to spare for training, the Army pilots practiced take-offs from a field marked with the size of a flight deck.

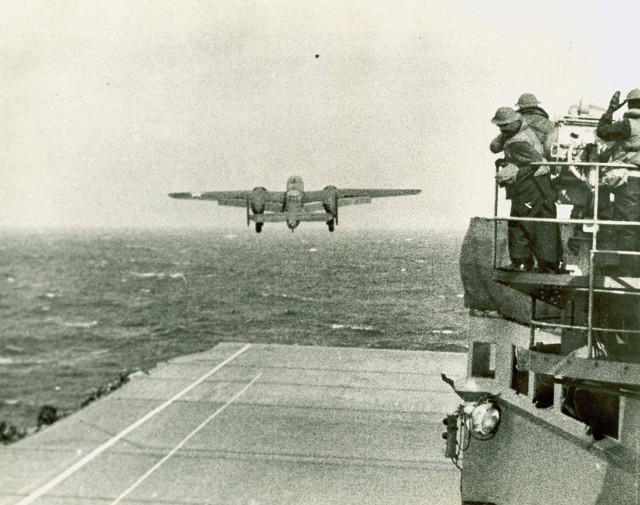

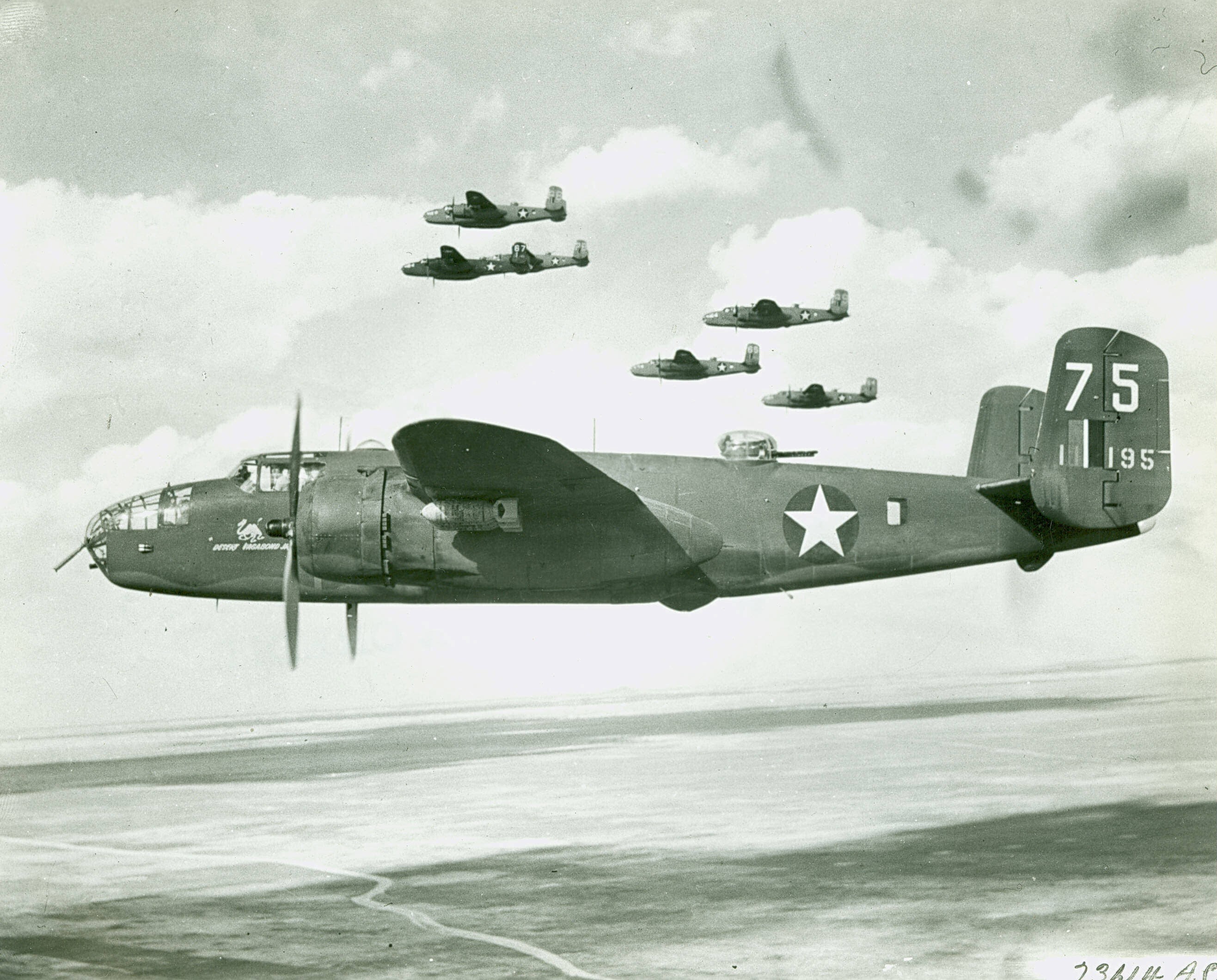

The raid plan called for the Navy to deliver the bombers to a point about 400 miles from Japan on April 18. This would leave them with sufficient fuel to land in friendly airfields on mainland China. Task Force 16 consisted of carriers USS Hornet, commanded by Captain Marc A. Mitscher, with sixteen Army bombers, and USS Enterprise, commanded by Admiral William F. Halsey, with Navy aircraft for security, and auxiliary vessels. At approximately 600 miles out, the Americans encountered Japanese picket boats which were quickly sunk; however, radio intercepts confirmed that the American fleet had been reported. Admiral Halsey ordered: "Launch planes. To Colonel Doolittle and gallant command, good luck and God bless you." The aircrews knew they probably had insufficient fuel to reach the Chinese airfields, and the early launch also prevented them from forming up into formation.

The string of thirteen American bombers began arriving over Tokyo at noon, and the aircrews were quite relieved when they encountered little opposition. They attacked military and industrial targets, inflicting minor damage but also hitting some civilians, and then winged toward China. The remaining bombers hit targets in Yokohama and Yokosuka. One-by-one, the aircraft ran low on fuel, and crews bailed out or crash landed along the Chinese coast; three airmen were killed. One aircraft landed safely in Russia, where the crew was interned for over a year. The Japanese captured eight and soon executed three. A fourth airman died as a prisoner of war. The heaviest toll was paid by the Chinese civilians living in the area where the raiders landed. Perhaps a quarter of a million were killed in retaliation.

The joint Army-Navy operation achieved limited tactical success but delivered a much needed morale boost to the American military and public. There was intense public interest in how the attack was launched. President Roosevelt facetiously said the raiders had come from Shangri-La, the name for his Western Maryland mountain retreat known today as Camp David. That name Shangri-La, in turn, derived from the popular 1937 movie Aca,!A"Lost Horizons,Aca,!A? set in a mythical mountain kingdom in central Asia, somewhat similar to Tibet. Wherever the raid supposedly originated, it greatly embarrassed the Japanese high command, and contributed to the motivation for the naval operation which led to their decisive defeat in June of 1942 at the Battle of Midway, a turning point in the Pacific War. The raid was also portent of the massive incendiary and nuclear bombing raids that brought Japan to surrender in August of 1945.

Doolittle expected to be court-martialed for having lost all his aircraft but instead received the Medal of Honor and promotion to brigadier general. He later earned his second and third stars and commanded the 12th, 15th and 8th Air Forces in the European Theater of Operations. He retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1959.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the: Army Heritage and Education Center, 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021.

Related Links:

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: Biographies-James Doolittle

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: US Army Air Forces

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: Japan WW2

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: Pacific Theater Overview

Social Sharing