Danger does not denote doom. Throughout military history, commanders have fought back against impending danger rather than yield to it. One such strategic leader was Robert E. Lee, commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Time and again throughout the Civil War, General Lee counterattacked Union attackers or even launched pre-emptive attacks before the Yankees could strike. This approach often produced favorable results. Earlier in the war, it enabled him to win many battles and campaigns; in 1864, it repeatedly blunted Bluecoat blows and slowed their juggernaut.

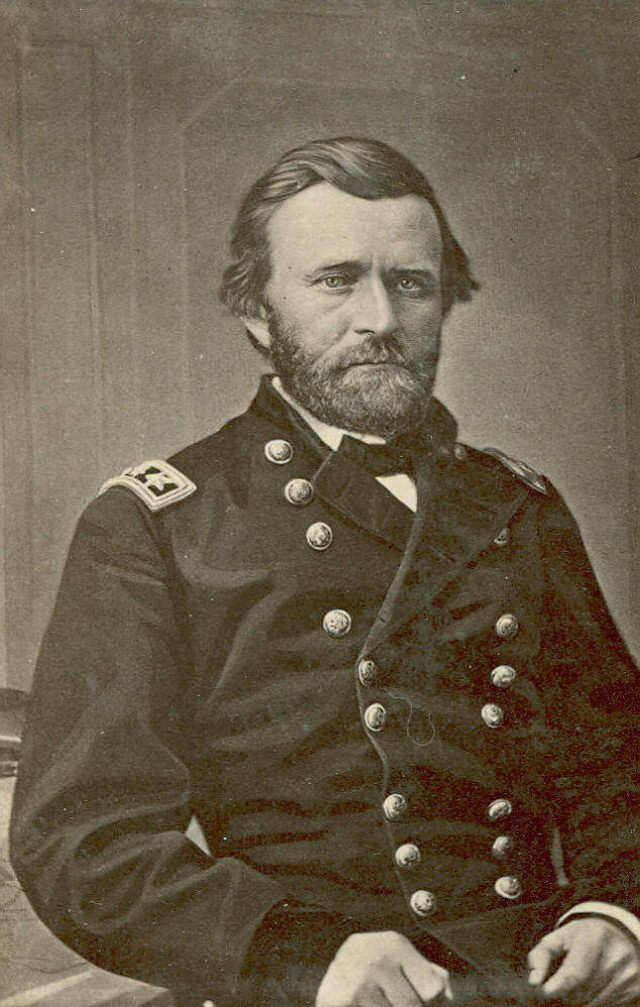

By March, 1865, however, the situation of Lee and the South had grown desperate. His own army was pinned down strategically in the trenches of besieged Richmond and Petersburg, while other Federal armies devoured the rest of the Confederacy. Five Northern divisions, fresh from victories in the Shenandoah Valley, had reinforced the Petersburg front the previous December to tighten the grip on Lee. Then in late March, two other victorious Valley divisions arrived opposite Petersburg. Clearly U.S. General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant was concentrating troops for the final offensive against the Confederate capital and its rail center.

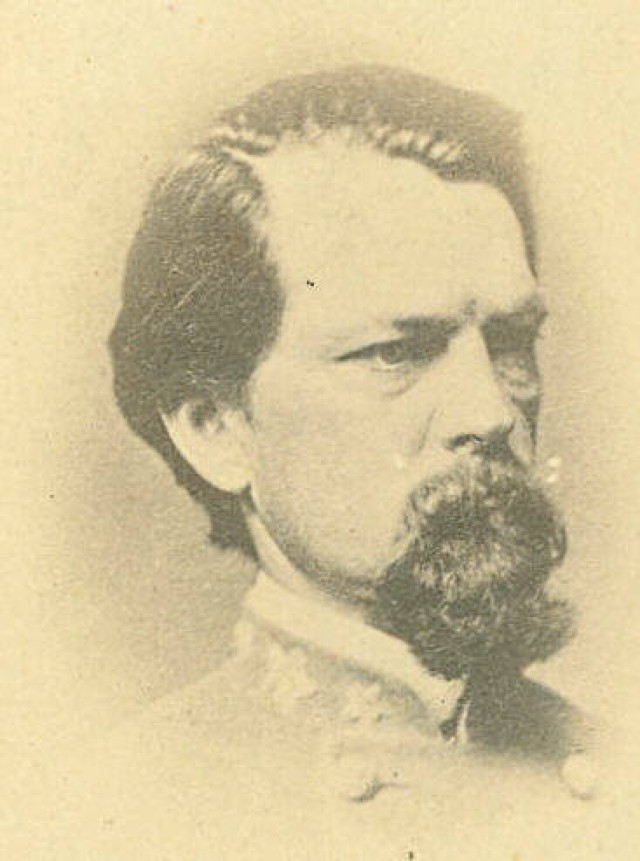

Lee struck first. Rather than allow the Northerners to continue dominating the course of operations, he unleashed twelve brigades under Major General John B. Gordon against the Union center east of Petersburg. Such a surprise attack on a sector that had not seen heavy fighting since July 30 offered much promise. If the Graycoats created even a temporary breach in the siege lines, the Unionists might have to pull in their left to restore their center. Making the left recoil would loosen the grip on Lee's army. He might then be able to detach forces for restoring the crumbling military situation in his strategic rear in North Carolina or even be able to break away from besieged Petersburg altogether, regain strategic mobility, and continue the war.

Before dawn, March 25, Gordon attacked. He captured Fort Stedman, three nearby batteries, and connecting trenches. Then his attack stalled. Efforts to expand the breach northward and southward were repeatedly repulsed. Nor could the Confederates drive further eastward to really rupture the Yankee position. Their surprise attack gained them only a small sector of earthworks, perhaps 500 prisoners (including a brigade commander) -- and the unenviable status of sitting ducks.

With daylight came the Bluecoats. The local Federal corps commander first contained the breach, and then counterattacked with his own troops, and recaptured Fort Stedman and the adjoining lines -- along with 2000 prisoners. Hundreds more Secessionists were killed or wounded as they withdrew westward through the crossfire raking the no-man's land between Stedman and their own lines. That retreat "was an awful time," recalled Lieutenant Thomas Brady of the 18th South Carolina Infantry Regiment; "our men were shot down by the dozens. I am thankful to God that he spared my life."

Meantime, the two Northern corps on the far left, rather than recoiling to restore the center, actually advanced and captured the fortified picket line southwest of Petersburg. Just four days later Grant launched his final offensive. From their forward position in those captured picket lines, three Blue divisions stormed the main Confederate works, April 2. Their success made Lee's position untenable. Overnight April 2-3, he evacuated both Petersburg and Richmond and began a desperate retreat southwestward toward North Carolina. He never arrived. On April 9, Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox.

Often during the Civil War, Lee had gambled, fought back, and won. This time his gamble failed, not just tactically but strategically. Not only did the Butternuts fail to break through the Federal center at Fort Stedman; they lost a key position further southwest which would cost them their capital. This time, too, as so often during that war, it was Grant and his senior subordinates who did not equate danger with disaster. They did not retreat before Gordon's attack but fought back. They not only restored their lines at Fort Stedman but also gained ground farther southwest where they would launch the decisive breakthrough.

In war as in life, nothing is inevitable. Brave Soldiers and capable commanders can fight back against danger and against the odds. Success is what we make it.

Related Links:

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: Petersburg

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: Civil War Confederate Biographies--John Gordon

Social Sharing