She was strange.

The local children called her the voodoo lady.

One day, she caught the neighborhood kids playing in her yard. She came out of her door screaming and all of the children ran - all except Charles Moss.

Although still a child, Moss knew he was wrong and chose not to run away.

In the face of the voodoo lady's wrath, he awaited his deserved punishment. She asked to see his hands.

He reached out, anticipating a smack on his offered hands. It was a different time - the 1950s - when the whole community would discipline children.

Moss knew of days when his mischief would cause so many spankings at the hands of others that by the time he got home, his bottom was too sore to feel any of his parents' punishment.

His hands in hers, the voodoo lady looked at him, as if scrutinizing a unique specimen. Moss caught her gaze and wondered what was going on, when she struck him with words, telling him that he had a gift "to see things others could not and the ability to tell those tales."

Her words were a blow that would stick with Moss for his entire life. The gifted hands the women refused to smack now play a deep role in who Moss is today.

A professional artist and non-profit organizer, his hands are the means by which he shows his audience the world he sees all around him.

However, although it was art that became his talent, Moss initially used his hands for something else: catching footballs.

Although small as a kid, Moss was an accomplished wide receiver in his neighborhood. Born in Beravard, N.C., Dec. 23, 1952, he was born into an era of segregation and played mainly with other black children in his neighborhood.

"I was born in the tail end of segregation. I went to school in a segregated school (Rosenwald School.) until seventh grade," Moss said. "I'd see 'colored' signs, colored drinking fountains and colored waiting rooms."

While the experiences from that time would go on to inspire his art, back then it was just the way things were.

However, the times began to change, allowing him to see a life of different possibilities. In 1964, two of his friends convinced him that they were good enough to play with white kids on the Brevard Little League football team.

"I started junior high school in 1965, one year after segregation," Moss said. "The principal told us (Moss and other black students) we had to succeed for all the students after us." Moss succeed academically and in football.

A quick receiver with good hands, he helped his football team go 13-0 and was rewarded with a full scholarship to Westin Carolina University.

Moss's love of football also steered him into his present lifestyle.

Moss had always captured his love of the game in his art (Moss said he drew football pictures at age 5), but college gave him the chance to truly study and practice, even to the point of drawing caricatures of his college teammates.

Although he earned a bachelor in fine arts (with a concentration in painting and drawing), his heart was still set on football.

"I tried out for the Atlanta Falcons and the CFL (Canadian Football League) and ended up in the World Football League with the Charlotte Hornets," he said.

The league eventually folded and Moss, driven by a need for adventure, decided to enlist for four years in the Army as a hawk missile crewmember.

Though trained as an air defense specialist, Mosss' artistic talent would take him away from the gun crew and into his battery commander's service.

"The attention started after I illustrated a flipchart for my lieutenant," Moss said. "The battery commander was so impressed he pulled me away to work for him."

With his artwork gaining prominence, he decided to pursue a career after leaving the Army, eventually being hired to a graphics job at Fort McPherson in 1980.

Today Moss serves as a visual information specialist with the Fort McPherson Training and Support Center. The job helps pay the bills on what Moss called a "starving artist's life."

"I couldn't afford brushes," Moss said, noting he was reduced to painting with a palette knife and credit cards.

"They (credit cards) got me in trouble, so I figured I'd use them to get me out."

Despite limited means, often painting on scrap poster board with oil paints or water-based acrylics and doodling on scrap paper with a ballpoint pen, the power of his pieces shone through.

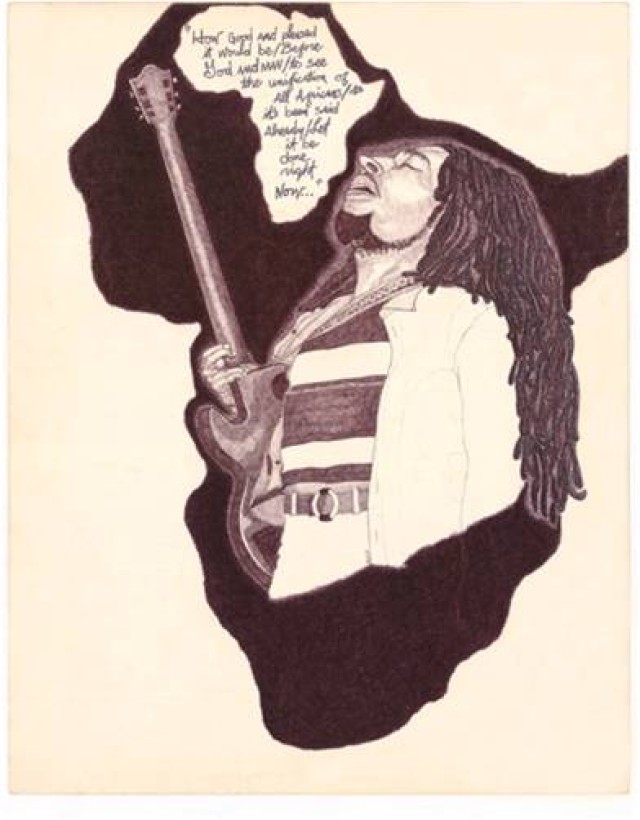

In addition to finding inspiration from his life during segregation, he also found inspiration from music.

"I'd paint from pictures and album covers," Moss said.

Moss said many times he would just listen to music and paint what came to mind.

"It's subconscious. I'll pick a background color, but everything else just comes," he said. "It's basically like free writing. Very rarely has it happened that I see the whole picture."

Musicians who see his works will often tell him that looking at his pieces is inspiring, Moss added.

"'This is what music looks like,' some would say," Moss said.

Although he has painted pieces based on the music of famous artists, such as Bob Marley, Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., his main inspiration still comes from capturing his experiences in a racially segregated environment.

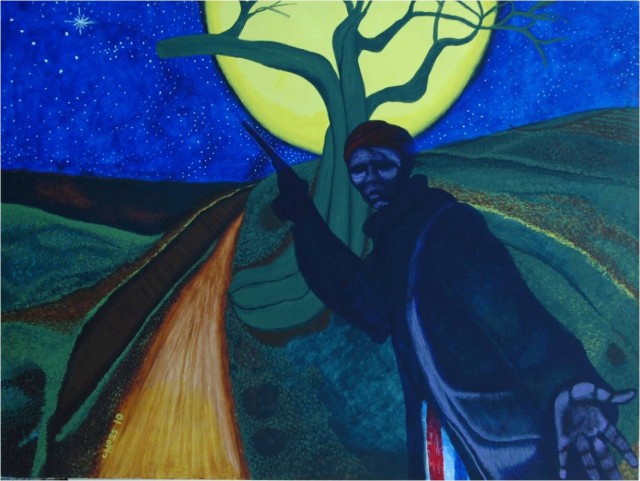

"I draw from the black prospective," Moss said, adding he feels he is finally able to give a voice to the hopes and dreams of his ancestors through his art.

Those ancestors who suffered under slavery aren't too far removed from Moss.

His parents were only the second generation of freed blacks, his mother's grandfather being born a slave in 1855 on the Ben Lyon Plantation.

He was born of a slave and her slave owner, which would show Moss how different whites and blacks were treated in his youth.

"My mom was fair skinned and light because my great grandfather was the son of a white slave owner," Moss said. "My mom would pose as white when she had to."

From this, he would see how his mother would get special privileges posing as a white, such as being able to get items before they were available to blacks in clothing stores. While some of Moss' pieces may be dark in theme, documenting slaves' suppressed cries for freedom, they also radiate a sense of color, said Zelmer Dawes,

U.S. Army Garrison Community Outreach Program specialist.

"African Americans have a rich history and for someone to be able to put it in a painting, he has to be very talented," she said. "He puts it in a way you can see and relate to. There's a lot of color and history in his art."

Dawes first saw Moss' work during a career fair day he was attending. He had brought some of his pieces along to illustrate his job as a graphic designer, and in addition to capturing the kids' attention, also caught hers.

Seeing the enjoyment the children received out of Moss' art, Dawes, who works with local schools on outreach programs, invited Moss to take part in some of these events, which he does now regularly during Black History Month.

It also led her to ask him to contribute to this year's Black History Month luncheon at Fort McPherson by contributing some of his pieces.

"They (the art pieces) were appropriate for that event. It is historical and has a message," Dawes said. Moss said he hopes to continue to use his art to convey to others what he sees.

To that end, in December 2009, he started a nonprofit organization called the Combined Art Center.

The Atlanta-based organization focuses on multimedia art education to local charities and is committed to using art as a tool of communication and opportunity for aspiring artists.

Additionally, Moss continues to delve deeply into the history of his ancestors, learning more about them to better tell their story and pay homage.

Next year he plans to take a trip to Ghana to visit the homeland of his ancestors.

Although it will be his first trip to Africa, it will be the second time he has interacted with natives of Ghana.

The first came in 2000 during a ceremony in Atlanta for the past residents of Ghana who participated in the Atlantic slave trade.

"Out of 45 slave councils, they found 38 in Ghana," Moss said. "They (representatives with roots back to Ghana slavers) were asking for forgiveness and atonement for their ancestors."

Though Moss granted forgiveness on behalf of his family to spiritually cleanse their hands, his own hands still have much to accomplish in telling his ancestors' tales.

"I feel I owe slaves something," he said of painting their struggles. "It really completes their dreams for freedom."

Social Sharing