WHEN Maj. Mike Walter makes the five-hour drive from U.S. Army Medical Research Unit-Kenya's Nairobi headquarters to the command's field stations in western Kenya, he brakes for zebras, warthogs and baboons.

As USARMU-K's chief of staff, Walter makes the trip often to check on teams of Soldiers studying diseases from HIV and malaria, to tuberculosis and diarrhea. The unit has grown exponentially in recent years, Walter said.

"The first time I made this trip was more than 10 years ago, when I was a new lieutenant. Back then, we ran our operations from small guest houses, old bank buildings and renovated shacks," Walter said, passing a matatu-a slow moving Kenyan shuttle bus. "Now we have state-of-the-art-laboratories, medical clinics full of high-tech equipment, and a robust administration to support our Soldiers in the field."

For the past 40 years, U.S. Army medical researchers have served in Kenya. The Nairobi-based unit is currently under the command of Col. Scott Gordon, a medical entomologist and 26-year Army veteran who holds a doctorate in microbiology. In 1969, Kenya invited U.S. Army researchers to study trypanosomiasis, a parasitic disease transmitted by the tsetse fly. In 1973, the unit was permanently established in Nairobi, working through an agreement with the Kenya Medical Research Institute, Gordon said.

"Since then, we've done quite a bit to improve health care in several regions in Kenya," Gordon said. "Our work also benefits U.S. Soldiers through research and testing that is then incorporated into Army medicine."

HIV research is top priority for U.S. Army and Kenyan researchers in Kericho, Walter's first stop, roughly a five-hour drive northwest from Nairobi. An area known for its tea plantations, Kericho also has a growing HIV infection rate-a perfect environment for USAMRU-K's researchers to study the disease when people are first infected.

Three years ago, Peter Kibet transferred from the Kenyan health ministry to the Walter Reed Project, what USAMRU-K is known as locally. Now, as Kericho's laboratory director, Kibet, 35, oversees a variety of programs, to include a current study into HIV.

"The patients of interest are those highly at risk for acquiring HIV, commercial sex workers and truck drivers," Kibet said. "Basically, we're trying to better understand the science behind HIV at the early stages of infection."

Young women, all volunteer participants, wait for the phlebotomist in a nearby tent. At first a large blood sample is drawn and tested, followed by twice-weekly small samples. This gives researchers the ability to capture HIV infection within a few days, Kibet said.

Inside the blood-drawing tent, Janet, a 23-year-old woman from Kericho, wears a heated mitt that makes it easier for phlebotomist David Wekulo to extract blood from veins in her hands. Wekulo, 34, from Kakamega, Kenya, joined WRP in 2009 after hearing of its successful research projects. When he and his colleagues in the nearby USAMRU-K laboratory-Kenya's only clinical research lab certified by the College of American Pathologists-learn that a volunteer is HIV positive, it's sad news, Wekulo said.

"Still, it's good they find out as early as possible so there are ways to intervene," Wekulo said. "Once enrolled in the study, they have access to medical care and social services through the Walter Reed Project."

In Kericho, USAMRU-K's primary objective is evaluating HIV candidate vaccines to support the development of a globally effective HIV vaccine-to protect U.S. military servicemembers, the local community and people worldwide, said Dr. Douglas Shaffer, a U.S. Army civilian who serves as director in Kericho.

In recent years, the research was coupled with comprehensive HIV care and treatment, an USAMRU-K initiative funded the through the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. In 2003, Congress authorized PEPFAR to provide millions of dollars in the fight against HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. In 2008, Congress reauthorized the plan, providing $48 billion over five years.

In Kericho, that meant increasing their ability to care for people infected with HIV. As recent as six years ago, HIV care in the South Rift Valley could rarely be found. In fact, less than two dozen people in the Kericho area received anti-retroviral treatment for HIV in 2004. Now, with help from USAMRU-K and PEPFAR funds, more than 40,000 Kenyans receive care and treatment, Shaffer said.

Care is now offered at 13 primary sites, normally in district hospitals and 36 satellite clinics set up in rural health centers. There are also 242 centers for expectant mothers-key sites for women to learn their status and prevent transmission to their unborn child with proper treatment, Shaffer said.

"We couldn't do HIV research without meeting the needs of this community. PEPFAR provided much needed funding," Shaffer said. "Integrating HIV research and offering comprehensive care meets our ethical obligation to the local people and from that we have gained community trust."

Connecting with Kenyans affected by HIV also happens on a much more personal level. USAMRU-K's HIV program extends to teens at the Kericho Youth Center, where adolescents learn about HIV infection and prevention through peer-to-peer education. The PEPFAR-funded program also reaches young people at the nearby Live With Hope Center, which helps orphans and other vulnerable children.

During Walter's visit, he also stopped at the Agape Children's Home, an orphanage where a couple dozen children-from toddlers to teens-live with HIV often contracted from parents who succumbed to the disease. Inside, Walter met Grace Soi, a former school teacher who was grateful to meet Shaffer and other WRP staff who recommend correct anti-retroviral treatment for the kids. Soldiers also bring them presents and milk from cows kept near USAMRU-K's Kericho guesthouse, she said.

"They don't directly fund us-but they help morally and at times financially though personal donations from American visitors Walter Reed brings when they stop by," Soi said. "They've given me so much advice on how to care for the children. That's been a great help to Agape."

Children's covered coughs remind visitors how their small charcoal fire barely heats the crowded room where they gather. Some kids get up and perform a song for Walter. Teenage girls giggle amongst themselves. Tiny eyes from the smaller ones sparkle in amazement at the Soldier who sits among them.

Talking later about the fate of the Agape children nearly brings Walter to tears, no doubt in part because he has four kids of his own.

"Seeing orphans with HIV brings it all full circle. We're studying infectious disease; they are the reason we do what we do," Walter said. "It's sad because children suffer from a disease we can treat, but not yet cure. But, as a Soldier and a medical researcher, it rejuvenates why you serve. You want to tackle it, hit the bench again. Despite the long hours in the lab, you're motivated to fix something, to find a solution."

USAMRU-K has a staff of 10 Soldiers, two Army civilians and more than 400 Kenyan contractors-a mix of doctors, nurses, scientists and laboratory technicians, who work together to research, test and prevent disease. They collaborate with Kenyan health officials, U.S. civilian and military organizations, private companies and universities, plus nongovernmental organizations and non-profit foundations. With the establishment of U.S. Army Africa, USAMRU-K is now coordinating its established missions with new Army initiatives on the continent.

U.S. Army officers on tour in Kenya live in rented housing, often with their families. Off duty, they spend time together. One night in Kericho, soccer fans gathered at Shaffer's house to watch Liverpool beat Manchester United over a Tusker beer and traditional Kenyan ugali (boiled corn flour).

Some, like Maj. Eric Lee, 38, of Pocatello, Idaho, are on short tours to study a specific topic. In Lee's case, it's diarrhea. At the Kericho guesthouse, Lee updates Walter on his work-a project on surveillance of diarrheal pathogens throughout Kenya.

"If we have U.S. Soldiers come to an environment that their bodies are not used to, then having a survey of diarrheal pathogens is extremely important," Lee said.

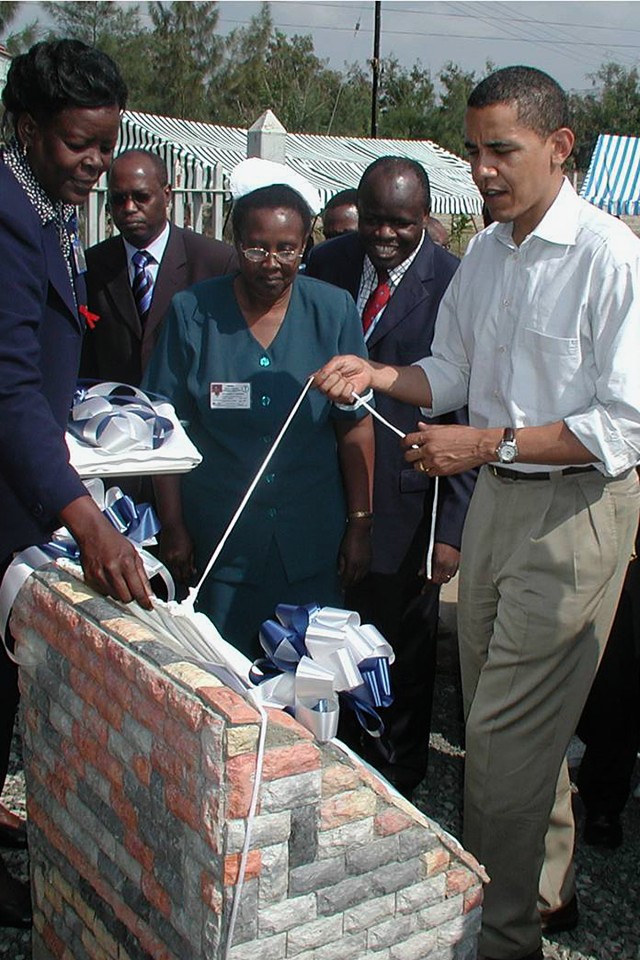

Walter's next stop is Kisumu, a 90-minute drive from the highlands near Kericho to the shores of Lake Victoria. He parks in front of the Kisumu field station, adjacent to the Kondele Children's Hospital, which was dedicated in August 2006 by then-Sen. Barack Obama.

Kisumu is the hub of Nyanza province along Lake Victoria. The area is the heartland of the Luo people in Kenya. President Obama's father came from the area and some of his paternal family still lives nearby. In Kisumu, researchers are mainly focused on malaria, studying potential vaccines and the ever-changing parasites that cause the disease. Currently, USAMRU-K is taking part in a vaccine trial that may produce the world's first malaria vaccine for children.

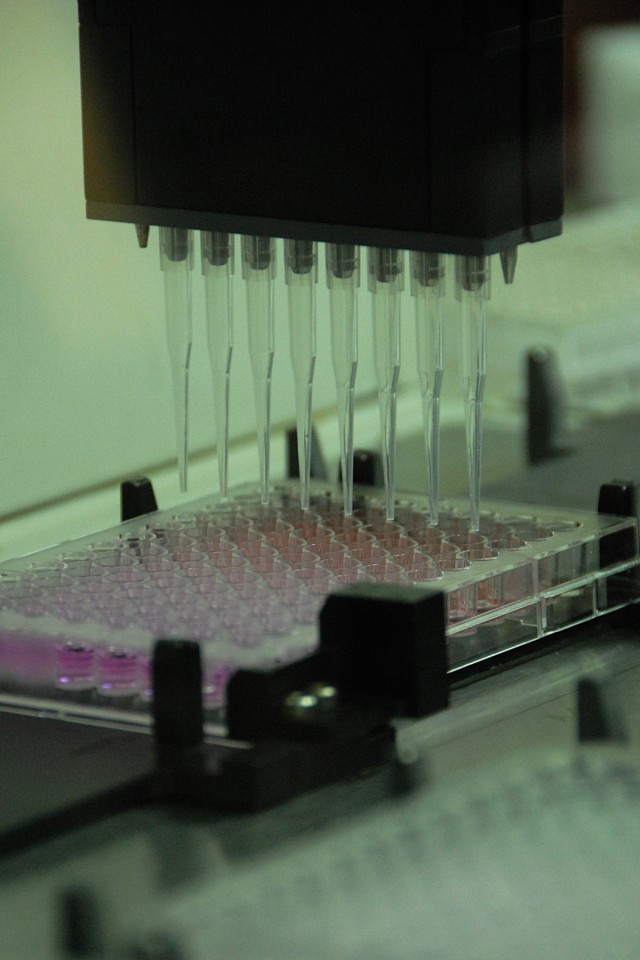

Maj. Charla Gaddy runs a laboratory that processes blood, urine, stool and other samples from people taking part in USAMRU-K research-up to 100 tests a day. She and her Kenyan colleagues make an impact on the lives of research participants-very young children who receive free health care for the duration of the three-year study, known to researchers at MAL-55.

"As a Soldier, a research scientist and a medical professional, I get to see the impact that USAMRU-K is having on the lives of people in western Kenya," Gaddy said. "Medicine that these kids don't normally get impacts their lives positively. Some of these kids are going to make it to adulthood because of the impacts of this study."

In the long term, Gaddy hopes the reality of a potential malaria vaccine will make a difference for the people of Kenya and beyond. Not a day goes by that Gaddy and her colleagues don't see and feel malaria's effects, from a co-worker out sick with fever to a child dying, she said.

"If this vaccine works, it will benefit not only the participants, but also the Kenyan people and people all over the world," Gaddy said. "I'm proud to be a part of Army research that might affect so many."

Before heading back to Nairobi, Walter talks with Maj. Eric Wagar, director of USAMRU-K's Malaria Diagnostics and Control Center of Excellence, about his recent trip to Nigeria. Since 2004, the center has hosted more than 500 students from 16 African countries in an outreach to improve the technicians' ability to read blood samples for malaria diagnosis.

"The program has expanded to offer malaria microscopy instructions and mentorship in Nigeria and Tanzania," Wagar said.

Walter and Wagar head to the cantina, where they have lunch beside colleagues from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention and Kenya Medical Research Institute, who are integral partners for medical studies in Kenya. Catching up with them is Capt. Jeffrey Clark, 34, fresh from his entomology research-catching, growing and studying everything from mosquitoes to sand flies. The Pennsylvania-native's insect-borne disease research helps the Army better understand diseases like malaria.

"'The best cure is prevention'; that's our motto in preventative medicine," Clark said. "If we focus on controlling the vector, we could get rid of malaria itself."

Saying farewell to his colleagues, Walter heads eastward back to Nairobi. Along the way, he's reminded why Soldiers are hard at work combating diseases in East Africa. USAMRU-K projects are making an impact-not only with U.S. military force health protection, but also with the Kenyan people, Walter said.

"You can walk into any one of our clinics, any day, and be touched by what you see," Walter said "That really sticks with you. You go home, look at yourself in the mirror and say, 'I did the military things, but I also made an impact on someone's life.'"

Social Sharing