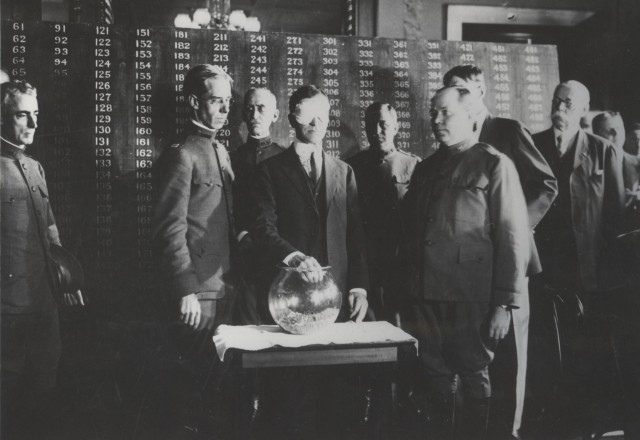

On June 5, 1917, some 10 million American men reported to their local Selective Service Registration Boards to register for service in the Army. It was a stunning example of mass compliance across a nation of great diversity and local loyalties. The Wall Street Journal hailed Registration Day as "the first real step to a spiritual realization of the fact of war by our intensely individualistic people." To fuel this enthusiastic compliance, the Selective Service System employed a combination of patriotic propaganda, such as the "Uncle Sam Wants You" posters, fan-fare, and competition between local counties. Not since the American Civil War was conscription employed to raise an Army. Unlike then, violent protests against the draft were minimal during the later period.

When President Woodrow Wilson asked for a declaration of war against Imperial Germany on April 2, 1917, the strength of the U.S. Army was around 110, 000 regular troops. To make the "world safe for democracy," President Wilson argued for a wartime Army based on "universal liability to military service." General John J. Pershing advocated the deployment of an American Expeditionary Force of almost two million by the end of 1918. The Selective Service Act was passed on May 18, 1917 to expand the existing peacetime, volunteer Army to a wartime Army. The Act required all able bodied men ages 21 to 30 (later extended to ages 18 to 45), to register for the draft regardless of race or religion. Exemptions were granted to men who had dependent families, indispensable duties at home, or physical disabilities. Conscientious objector status was granted to members of pacifist religious organizations, but they had to perform alternative service. By the end of World War I, some 24 million men had registered, and some 2.8 million were drafted.

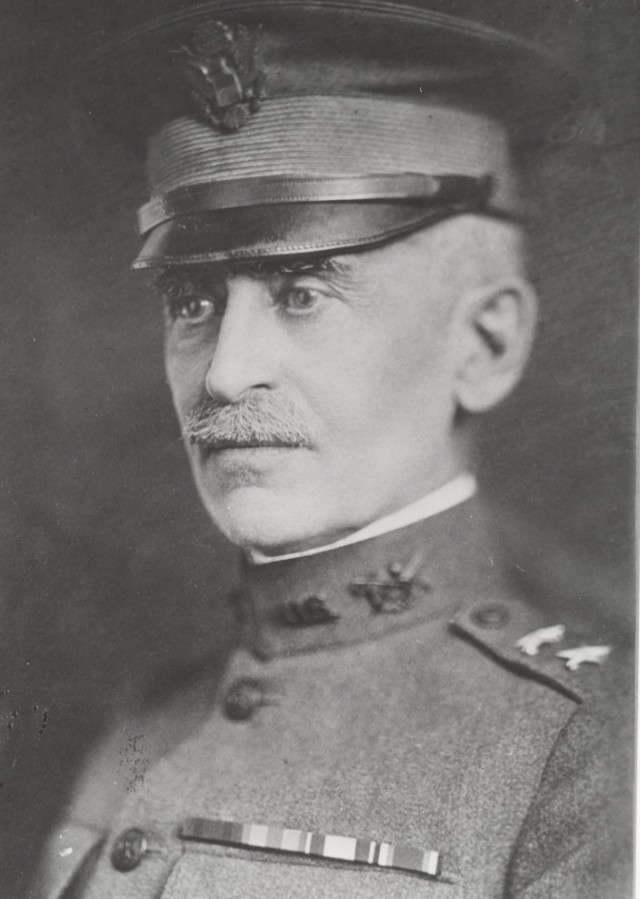

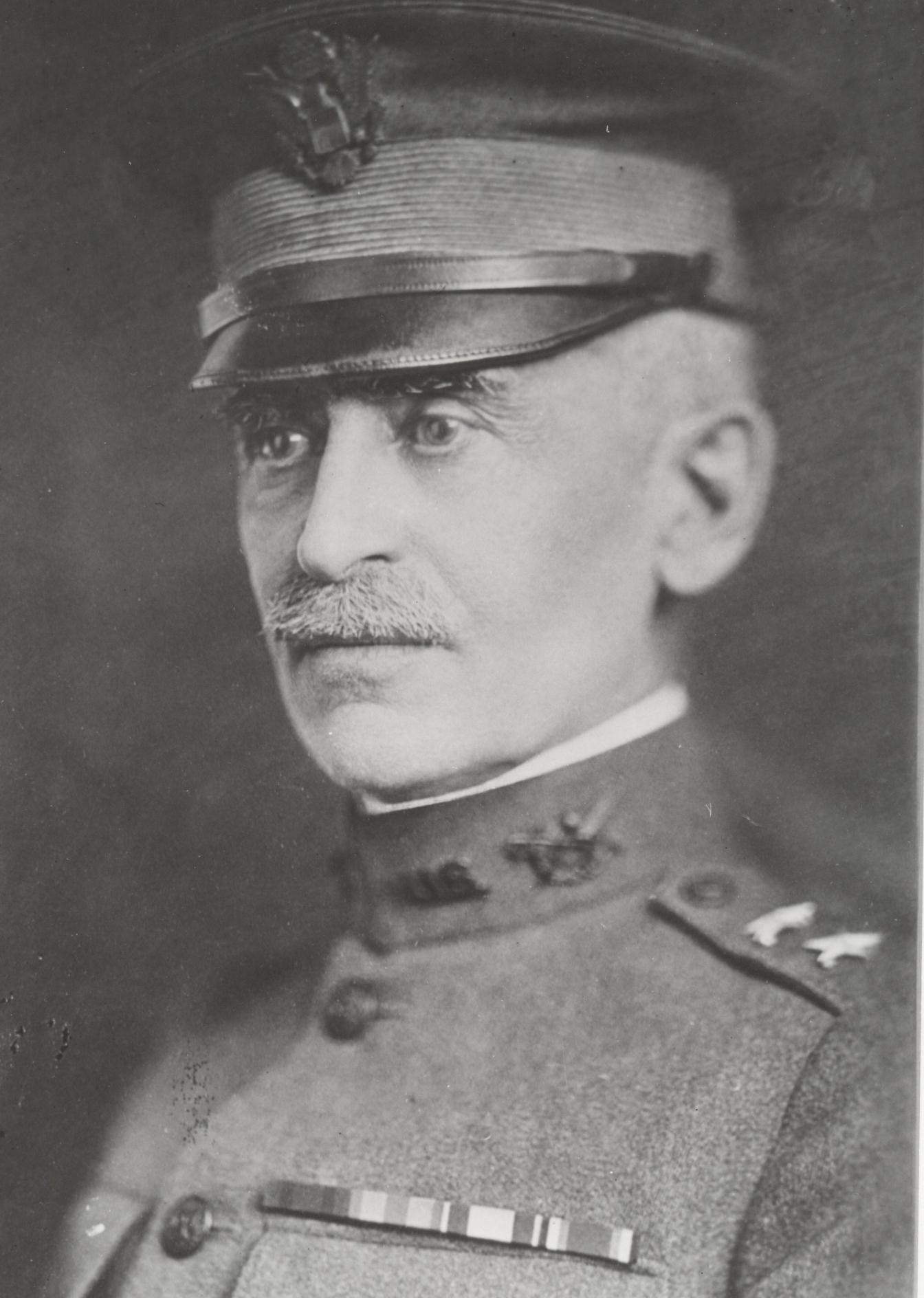

On May 22, 1917, under General Orders Number 65, Brigadier General Enoch Crowder, the Army's chief legal officer, was detailed as Provost Marshal General and charged with the administration of the laws and guidelines promulgated in the Act. As a young officer, he had served in the cavalry. In 1899 he had occasion to study the reports on Civil War conscription by General James B. Fry, who had charge of the Draft, 1863-1865. His study of history would one day inform his decision making and ultimately help shape the United States Army for war. In February of 1917, President Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker consulted with BG Crowder regarding the possibility of a draft. General Crowder dusted off General Fry's report to help develop the policies, language, and guidelines that would authorize the President to "...increase temporarily the Military Establishment of the United States." Thus, the Selective Service Act of 1917 was born.

The act proved successful in achieving its military goals of filling the increasing demands for soldiers during the ensuing eighteen months the U.S. was engaged in Europe. It avoided the Civil War era pitfalls and provided a means to harmonize military requirements with industry to avoid shortages in the labor force.

Socially, the Selective Service Act advanced American society towards achieving equal status for all its citizens. African Americans served not just as labor or pioneer troops, but effectively as combat troops, although in segregated units. To maintain the industrial base, women and other minorities were amalgamated into the work force. While equal citizenship, undergirded by law, was still a generation or more away, the mold was cast.

The Selective Service Act of 1917, though not without its shortcomings, provided the most successful argument for conscription up to that point. The model survived through three subsequent wars until the Army adopted an all volunteer force in 1973. Conscription is no longer employed but today's Army, like the Army of 1917, retains an expansible quality to meet the nation's requirements.

Related Links:

Civil War Conscription, 1862-1865

Conscription In World War I & U.S. Citizens Already Serving In Foreign Armies.

Social Sharing